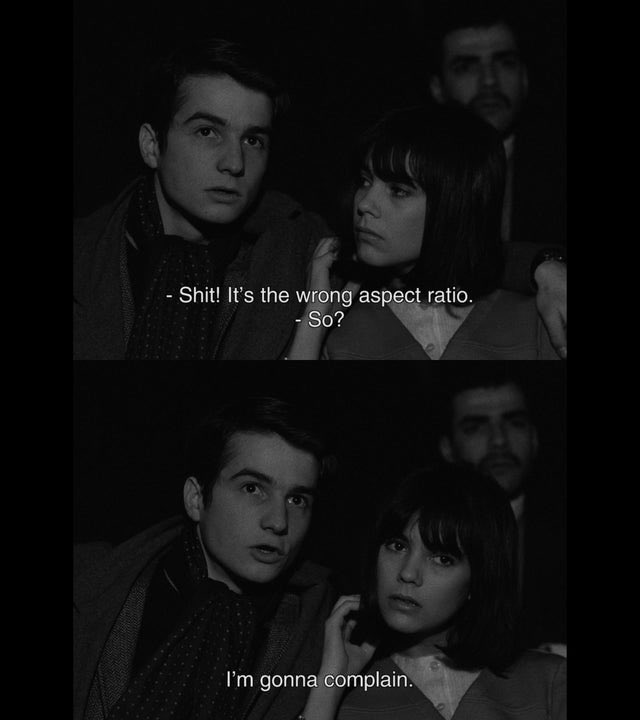

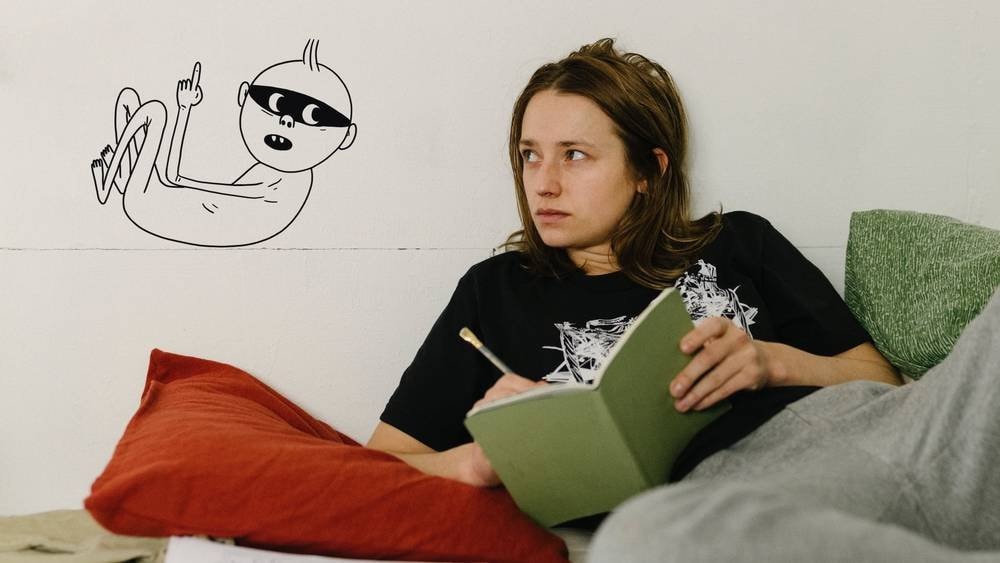

~What is your greatest ambition in life? To become immortal then die~ REMEMBERING JEAN-LUC GODARD10/19/2022 totally sober musings from a first time blogger by Ian Kammerer This year, we lost a filmmaker who grew into one of cinema’s all-time greats, Jean-Luc Godard. Godard, like directors like Leos Carax, Ozu, and Fellini, is one of my favorite directors that makes movies that are self-aware, self-reflexive, and above all, about lived experience and reality, bringing us affectively into the “here and now” of the film. And Godard’s Breathless is no exception to this. The Roxie Theater in SF has been paying tribute to Godard by screening his films in 16mm or 35mm this month. Breathless follows hopeless romantic and drifter Michel Poiccard a.k.a. Laszlo Kovacs as he evades law enforcement (and true love), leading to an unforgettable final sequence that, if it doesn’t make you break down in tears, warrants a visit to the nearest therapist. Godard makes you fall in love with citizen so-and-so Kovacs despite the gaping holes in his character (which seem somewhat irrelevant by the final scene — new wounds have opened up). A film full of pseudo-intellectual musings, existentialist pipe-dreams, and genuine reconciling with love, the spectator becomes entranced by the story as they seamlessly stroll down the Champs with Laszlo. Breathless scratches that trial and error, start / stop, always bounding forwards itch of some of my favorite films, but takes it a step farther than films like Umberto D or The 400 Blows. The sing-song dialogue of Laszlo and Patricia, which like the actual sing-song lovebirds Genevieve and Guy from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, end this fateful tale in heartstring-plucking resolutions. What stuck out to me was the underlying theme of the dangers of the ego in the modern era. Laszlo is constantly interacting with performance, from speaking to a headshot of “Bogey” and proclaiming the famous “a Cinecittà!” to making faces in the mirror to Patricia and himself. The stress of the dangers one encounters when overly-indulging in themselves and their ego, paired with technology comes through in the film strongly. Now, even more than in 1960 when the film came out, do humans have the technology that can do almost everything we used to do for ourselves but have not a clue or hair of moral forthrightness and fortitude to know how to use it responsibility. This fear looms over us in Breathless, adding to the general doom and agony of the film’s emotional superstructure Similar to my favorite film of 2021, The Worst Person in the World, Breathless uses the cinema as a quasi-theatrical, quasi-personal monologue yet liminal space where once self-indulgent diaries seemed pretentious and egotistical, now seem interested, genuine, and necessary. Breathless does something that precious-few films of late do, which is to tell the truth. Godard tells it to us straight. Shit happens. Love fails. Truth evades honesty. “Informers inform. Burglars burgle. Murderers murder. Lovers love.” And above all else, “There’s no need to lie. Truth is best.” Thank you Godard, for having the power to tell the truth. You have become immortal to us through your films, which will live on in our minds like the last touch of a lover lingers on our lips. Until next time.

FIN

0 Comments

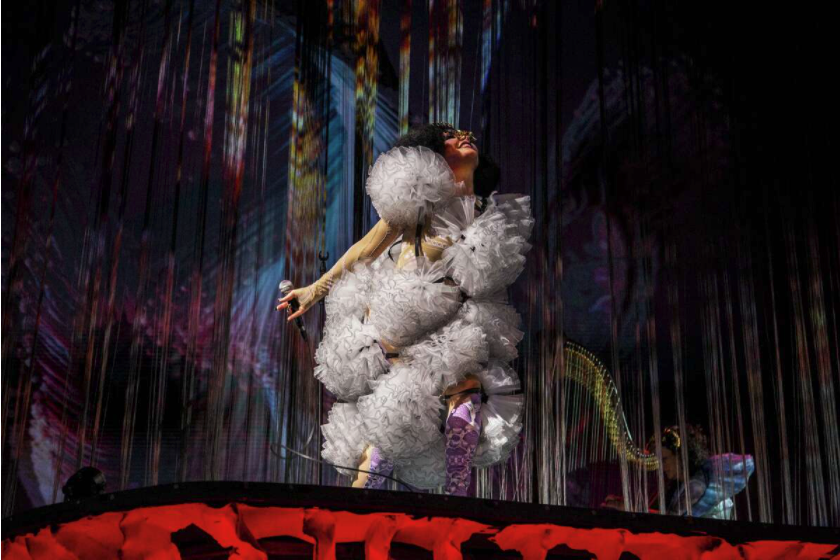

via dailybeast by Phil Segal 1. Crime in General

Lately I’ve been thinking about crime. It’s a genre I always find myself drawn to. And, I’ll admit, something that makes writers and artists interesting to me, hence the Jean Genet biography sitting on my desk as I type this. I’m not remotely above considering tabloid interest in criminality, strange deaths, or otherwise unusual life stories of the people involved when making decisions about what to read or watch. But this is not about Sartre’s saint, although reading Querelle a couple months ago was a revelatory experience. I want to focus on crime writers here, not criminal writers. A number of times, often for months, I’ve lost the ability to read, or more accurately what I’ve lost is the ability to compel myself to pick up a book that I don’t specifically have to read even though I desperately want to read. I’ll stare at books, maybe get a page or two in, but be completely unable to commit to actually reading a book. Trying to find my way into books and failing, hitting walls. I’m still interested in books, I can read articles about them, posts about them, book reviews, Wikipedia pages about books. And I do. And I continue to look for books and pick up books I want to read, hoping to find the one that breaks my reader’s block. And often that book is an old crime novel. Recently, in fact, I’ve been alternating crime novels and heavier stuff to keep my reading momentum up successfully. It’s partly that old crime novels are written to be quick, easy reads. It’s a genre full of books that are around 200 pages or less with short chapters and a lot of stuff happening. Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest, a foundational text in the modern American strain of crime writing that the French that would dub roman noir, has something like twenty deaths in its 225 pages (and probably a dozen double crosses). That invocation of the French displays another part of the appeal: reading crime novels isn’t just fun; if you’re so inclined, you can make your habit sound downright respectable with reference to European intellectual appreciators, or Fredric Jameson. I certainly plan to in this essay. But more importantly, it’s a genre full of writers with distinct personalities and styles. As with the film noirs frequently adapted from their writings, if the authors could work within the standard, formulaic plots then the editors and publishers didn’t mind them using those plots as a framework from which to hang personal quirks, stylistic tics, satire, and social criticism. Of course, most people were just writing to pay the bills (which can still produce enjoyable writing), but there are plenty of those writers who brought something extra to the table. I’d like to tell you about two of those writers, Dashiell Hammett and Jean-Patrick Manchette. I didn’t originally mean for this to go on so long; whenever I try to think of an explanation, all that comes up in my mind is a phrase repeated throughout Jeanette Winterson’s The Passion: “I’m telling you stories. Trust me.” I found a subject I’m passionate about. I want to tell you some stories. Trust me. 2. Hammett: The Basic Story V.S. Naipaul once wrote that, “A writer is in the end not his books, but his myth.” Dashiell Hammett is more of a myth than most. He was famously a Pinkerton operative from 1915-1922 (with a break to serve in WWI, during which time he caught Spanish Flu and tuberculosis, from which he would never fully recover) who drew on those experiences to transform crime writing in the twenties and thirties with short stories in the influential early pulp magazine Black Mask, where he started publishing stories in 1923. Between 1929 and 1934, he published five books, which were initially published as serials in Black Mask before being collected and partially rewritten to make them work as novels. The one exception was his last novel, 1934’s The Thin Man, initially published in Redbook of all places (apparently at the time Redbook was also publishing writing by Fitzgerald and Tarkington). After The Thin Man, he didn’t publish any more books, though he lived until 1961, and though there was definitely an audience for sequels to The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man (as shown by the five(!) sequels to the 1934 film version of The Thin Man, beginning with 1936’s After the Thin Man). The ex-Pinkerton and possible strikebreaker — a story long circulated that Hammett was one of the Pinkertons employed by the Anaconda Copper Mining Company to take on strikers in Butte, Montana in 1917, where International Workers of the World organizer Frank Little was lynched (the story, relayed by Lillian Hellman in one of her memoirs, is most likely false) — became involved in the mid-30s with left-wing playwright Lillian Hellman (his partner for the rest of his life), turned radical, and joined the American Communist Party in 1937. He served in WWII, but after the war, during the blacklist era, wound up in prison on contempt charges in 1951 when he was called in front of HUAC and refused to name names of contributors to a bail fund for arrested radicals. In 1953 he was again called in front of HUAC and again refused to name names. He wasn’t sent to prison a second time, but he couldn’t get work and the IRS was hounding him for $175,000. He had failed to file his taxes while he was in the Army during WWII, that only accounted for a small part of the money owed. It was primarily a form of economic sanctions. He died impoverished, his books out of print in America, but Lillian Hellman secured the rights to his writing and worked to get it back in print and tell his story. His books were reissued, rediscovered, and eventually even collected in a Library of America edition. His rehabilitation and reintegration into American culture is at this point complete. 2.5. McCarthyisms or The More Complicated and Accurate Story There's an important follow-up sentence to the previously quoted Naipaul line: “And that myth is in the keeping of others.” Lillian Hellman was the keeper of Hammett’s myth until her own death in 1984, and she’s an important part of how Hammett has been understood. As I alluded to before, some of the stories she circulated about Hammett, like his presence at the crushing of the Butte strike, are almost certainly false. Her plays The Children’s Hour and Little Foxes are probably her best remembered works now since both were turned into well-regarded films. What’s pertinent here, though, are her entertaining memoirs, 1969’s An Unfinished Woman, 1973’s Pentimento, and especially her recounting of the Blacklist era, 1976’s Scoundrel Time, where she presented an image of Hammett and herself as political mavericks, Hammett a Communist party member and herself more of a “fellow traveler” but both willing to push back on the party line when they disagreed. Events in her memoirs were challenged by Martha Gellhorn (she thoroughly debunked Hellman’s account of her time in the Spanish Civil War and meetings with Hemingway in An Unfinished Woman) and, most famously, Mary McCarthy (no relation to Joe), who said on a 1980 episode of The Dick Cavett Show that, “every word [Hellman] writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the’.” It’s a line so good that it inspired Nora Ephron to write a play, Imaginary Friends, about Hellman and McCarthy continuing their conflict in Hell. McCarthy, a writer and public intellectual who had been a Communist-sympathetic “fellow traveler” until the Soviet Union’s show trials and purges during the 30’s, and some American Communists’ defenses and denials of them, pushed her to become part of the anti-Communist left centered around the magazine Partisan Review, contended that Hellman had been a Communist Party member and not just a “fellow traveler,” had in fact had been a hardline Stalinist, a prominent defender of the show trials and purges, and was just generally a fabricator (on a semi-related note, I read McCarthy’s novel The Group last year and highly recommend it). She particularly took issue with Hellman’s claims that anti-Communist leftists and liberals such as the Partisan Review group had failed to take a stand against (Joseph) McCarthyism, while a review of the historical record showed that while their legacy was certainly mixed, anti-Communist leftists and liberals like the Partisan Review, Mary McCarthy, and Hellman’s own lawyer during the HUAC hearings, to cite a few examples, all took public stands against the HUAC hearings as they were happening in spite of reservations about the Communists. Hellman sued McCarthy for her libel, which turned out to be a mistake, because as soon as people began fact-checking her memoirs to prepare for the trial they turned out to be full of fabrications and distortions. The biggest deal was the “Julia” section of Pentimento, a story about Hellman risking her life to smuggle aid to anti-Nazi resistance efforts in German territory in the late 30s, which had been adapted into the 1977 film Julia, which was nominated for eleven Oscars and won three. It turned out that the events were substantially true, but that they’d happened to someone else and Hellman had stolen them to present as part of her own life. Hellman’s death brought the suit to a halt. (Ruth Franklin’s review of Alice Kessler-Harris’s biography of Hellman is a relatively quick way to get a useful, sympathetic but frank account of Hellman’s life and her side of the conflict. It concedes that Mary McCarthy’s charges were true, but makes a fair attempt to understand her motives and legacy). As regards Hammett, the “maverick” portrait she’d painted had required the writing out of regrettable instances like his switching briefly from anti-fascist advocacy in the beginning of WWII to isolationism following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as part of his general sticking to the Soviet party line, and exaggerated stories like his presence at the Butte battle. In fact, in her telling not only had he been sent there by the Pinkertons to put down the strike, while there he’d been approached by men offering money for the killing of Frank Little, which he’d turned down only to see Little lynched anyway. His resulting disgust, in this telling, wasn’t necessarily a full Road to Damascus moment, but it was when his journey towards the political left began. It’s a very dramatic, compelling story, but, again, it almost certainly never happened. From after his death until her own, though, she controlled access to Hammet’s books and papers and so on, so any biographer had to go through her, resulting in inaccuracies in a number of Hammett biographies. In spite of the untruths, Hammett’s reputation came out mostly unscathed. It helped that by the time of the lawsuit and attendant scandal his books had already been reprinted and reembraced, and any lapses could be explained away as well-meaning but misguided idealism by anyone inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt or overlooked entirely since his Communist Party membership began after the novels stopped, and we as a culture tend to be willing to excuse and overlook much worse than that from a white guy who’s written well-liked books. It also helped that he’d been dead for years by the time Hellman’s memoirs started coming out, so no one held him responsible for any of the falsehoods about his life. He had also been a serial exaggerator during his life, and some of the falsehoods Hellman wrote down had definitely come from him, but his name wasn’t on the memoirs and he wasn’t part of the lawsuit, so Hellman ended up taking the fall for all of it. Still, even if things weren’t as dramatic and consistently admirable as Hellman had portrayed them, that didn’t mean Hammett’s life lacked for dramatic or admirable moments. He really had been a Pinkerton that later become radicalized, although it seems it was the Spanish Civil War that did it more than his Pinkerton experiences. And the regrettable WWII isolationism only lasted until America entered the war, at which point he switched back to anti-fascism and enlisted in the army. This took some maneuvering because he was almost 50, had never fully recovered from the tuberculosis he’d caught during WWI, and was an active member of the Communist Party, but he managed to enlist and serve. And during the Red Scare he really was willing to take a principled stand in front of HUAC and serve time in prison and suffer financially for it. I prefer Mary McCarthy as a writer and person, and I find the way Hellman rewrote political history ethically questionable at best, but Hellman was a great literary mythmaker. Hammett’s reputation and legacy owe a lot to her, for better and worse. 3. The Op However one feels about Hammett’s life, and however fascinating his life was, the reason anyone bothers to learn about his life is because of the writing he produced during it. So far, I’ve read his first two novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, both of which star the Continental Op, an unnamed agent employed a Pinkerton-style outfit who starred in many of Hammett’s short stories. He’s described as a short, stocky middle-aged man, cynical and tough and willing to use dirty tricks if need be but with a sense of duty to his job and a genuine interest in sorting things out. I’ve been picturing Bob Hoskins. In Red Harvest, he’s sent to Personville, referred to as “Poisonville” by everybody who knows the place, and sets about cleaning things up. The way he cleans up the town will be familiar, in broad strokes, to anyone who’s seen Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, or Sergio Leone’s uncredited remake of Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars. Our unnamed mercenary rides into a town run by rival gangs and works on turning everybody against everybody else, shattering every fragile alliance in hopes that all the town’s problems will wipe each other out. Kurosawa credited Hammett as an inspiration but somewhat confusingly claimed it was Hammett’s fourth novel, The Glass Key, and its 1942 film version that he based Yojimbo on in spite of the much closer resemblance between Yojimbo and Red Harvest. The Coen brothers’ first film, Blood Simple, gets its title from a line in Red Harvest, and they’ve claimed that Miller’s Crossing is an adaptation in spirit of Red Harvest and The Glass Key (it borrows more from the latter). Throughout the 70’s into the early 80’s Bernardo Bertolucci tried to get an adaptation off the ground starring Jack Nicholson as the Op but it never ended up happening. I had a great time reading Red Harvest. As I previously mentioned, it’s a fast-paced story full of frequent murder and double-crosses; there is ostensibly a mystery for the Op to solve, of a newspaperman’s murder, but it reads as an action novel, not a detective one. Too many plot developments and characters are introduced too quickly for the Op or the reader to do anything but roll with punches. There’s not a lot of time to consider clues when rival gangs are launching drive-by shootings on each other’s speakeasies and tossing pipe bombs, when our hero will suddenly get the idea to using blackmail to fix a boxing match just to see what kind of chaos he can cause. It’s a book that gets so out of control that the only way to end it is calling in the National Guard. Every page has lines like this, from a scene where the Op and a man who knows that the Op knows incriminating things about him are simultaneously contemplating how to get the upper hand as soon as one of them inevitably makes a move: “He stood at the foot of the bed and looked at me with solemn eyes. I sat on the side of the bed and looked at him with whatever kind of eyes I had at the time. We did this for nearly three minutes.” It’s a story of venality, vice, and violence delivered with a pretty deadpan, matter-of-fact style and plenty of black comedy. You can see why he’s a favorite of the Coens. Some Hammett scholars have argued pretty convincingly that Personville is probably based on Butte, Montana in the aftermath of the mining company crushing the strike (see J.A. Zumoff for a good summary). Even though the stories of Hammett’s direct involvement are almost certainly false, he would have been familiar with the Butte strike. The story of Personville’s descent into Poisonville is relayed to the Op on his arrival by a “wobbly” (that’s an IWW organizer) who explains that Elihu Wilsson, town bigshot, hired goons to take care of a strike using whatever force they felt necessary. Unfortunately, “old Elihu didn’t know his Italian history” and once the goons had taken care of the strikers, they took over the town, blackmailing Elihu with his complicity in what happened during the strike-breaking and terrorizing everyone else. Some Hammett scholars have also argued, based on this, that the seeds of Hammett’s later turn to Marxism are evident in Red Harvest (see Zumoff again for a consideration of that claim, which he doesn’t find very convincing). I think it’s more amusingly cynical than coherently political, and my primary reason for recommending it is pure enjoyment. The characters are one dimensional, the escapes are frequently implausible, and plot developments prioritize excitement over sense, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. Trying to “improve” the book would just slow it down. The Dain Curse, published a few months after Red Harvest in 1929, is generally considered the weakest of Hammett’s novels. Having only read the two, all I can say for sure is that it’s not as good as Red Harvest. It wasn’t exactly serialized in Black Mask initially, instead it was what’s known as a “fix-up,” a reworking of pre-existing short stories that weren’t originally conceived as a continuous story into a novel, done fairly quickly to keep up the momentum from Red Harvest’s success while he worked on The Maltese Falcon. In this case, four short stories became a novel with three sections, each focusing on a separate case that somehow involves one Gabrielle Leggett. Leggett is convinced that the curse of the title is responsible for the run of bad luck surrounding her, while the Op is sure that there’s no such thing as a curse and, in spite of the apparent solutions he finds at the end of each section, believes that there must be some angle he’s missing. Things get really outlandish, with a story that begins with a simple diamond theft soon escalating to include daring escapes from Devil’s Island, a San Francisco cult, ghostly visions, kidnappings, bombings, and a few dozen characters, all in just over 200 pages. Hammett does seem to be trying something here, because he has the Op consult and argue with Owen Fitzstephan, a novelist who insists that all this melodrama is exactly how a crime story should go, much to the Op’s chagrin. It often seems like it might tip over into parody, and maybe parody is the best way to justify the not very persuasive or satisfying conclusion. Hammett himself agreed with the general consensus and later dismissed the book as “a silly story.” It’s not entirely without defenders; Isabelle Boof-Vermesse, for example, sees it as an illustration of chaotic systems in a logical sense (the article, by necessity, spoils the plot of The Dain Curse early and often). I’d call it a very flawed book, not a failure but a book it’s unlikely anyone would pick up today if it weren’t for Hammett’s other books. The Op does more detective work in The Dain Curse, but the continuous introduction of new characters and plot elements again means that the reader just has to go along with the story and not try to solve it. He gets in some good lines, but not nearly as many as in Red Harvest, and for most of the book is less charming as a consequence. His interactions with non-white characters, mainly the Leggetts’ African-American maid, are, considering it’s 1929, not awful, but they’re hardly great and they’re definitely not going to endear the Op to modern readers. Still, in spite of its many flaws, The Dain Curse isn’t devoid of enjoyable parts. Two sections in particular, the San Francisco cult and the Op’s efforts to help Gabrielle Leggett beat her heroin addiction, stood out to me. While the Op has fewer good lines this time around, he does get in a solid one about the cult, the Temple of the Holy Grail, which is a new age mystical thing attended largely by the fashionable rich: “They brought their cult to California because everybody does, and picked San Francisco because it held less competition than Los Angeles.” But there’s a lot of dialogue like this: “Gabrielle was always, even before she became addicted to drugs, a child of, one might say, limited mentality; and so, by the time the London police had found us, we had succeeded in quite emptying her mind of memory, that is, of this particular memory.” The comma abuse makes it read more like one of my sentences than Red Harvest, and it also provides an idea of the kind of convoluted and very silly plotting, which requires large portions of the book to be people explaining things that have happened to each other (again, more like my writing than Red Harvest). In spite of the minor letdown of The Dain Curse, which I wasn’t expecting a ton from anyway given its reputation, I’m looking forward to continuing with Hammett, because for the most part people agree that The Maltese Falcon and The Glass Key are his best, and even The Dain Curse, which is supposed to be his worst, was an okay time. 4. Manchette: The Basic Story What led me to finally get around to reading Hammett was a recent addiction to French crime writer Jean-Patrick Manchette, a Hammett devotee. Manchette was born in Marseille in December of 1942, a month after German and Italian forces had occupied the city. He studied English literature at the Sorbonne and contributed to the left-wing paper La Voie Communiste in opposition to the Algerian War. In the 60s, he and his wife Melissa began translating American crime novels for Gallimard’s Serie Noire imprint. During this same period Manchette embraced the “libertarian Communism,” as an authorial stand-in in one of his books refers to it, of the Situationists and Guy Debord. France had an active Communist Party that stuck to the Soviet party line, and in the late 60s Maoism enjoyed a brief vogue and this caused a lot of internecine sparring in addition to sparring with the Socialist party. Manchette and Situationists like Debord that informed his thinking opposed the repressive “state socialism” of the Soviets and the Chinese, but still considered the Socialists too moderate, making them something of a fringe within a fringe. I wouldn’t quote me on the factions of the French left, I don’t speak French, it’s all highly complicated, and I have classes I’m supposed to be doing work for right now which has limited the amount of research I can do for this essay, but this is what I’ve picked up. Like many French of his generation, he was profoundly affected by the events of the May 68 uprising and the failure of the left to convert all the energy and momentum into a political victory. The internecine sparring among the left didn’t help, but more important was the failure to sustain and further build the alliance between the radicals and the workers that briefly emerged during the mass strikes (again, I wouldn’t quote me on this). Manchette seized on crime writing, and, in particular, what he dubbed Hammett’s “behaviorist” style of crime fiction, a focus on the purely external, visible elements of the world and the characters in it, to channel his disillusionment. He noted the similarities between Hammett’s prose and Hemingway’s, which emerged around the same time, but dismissed Hemingway as “inferior because pretentious.” Between 1971 and 1981 he wrote ten books published by Serie Noire that reinvigorated French crime writing. After the tenth, The Prone Gunman (La Position du Tireur Couché in its original French), he took a break, feeling there was nothing more he could do with the crime novel except repeat himself. He also wrote essays on noir and politics, screenplays (primarily pure “for-hire” work), and film reviews, although little of this writing has been translated. His journals have also been released posthumously in France. The few essays that are translated are hosted on the Marxists.org database. At the time of his death from cancer in 1995 he was preparing to launch a new cycle of novels, a series of globe spanning adventures covering the second half of the twentieth century decade by decade, with a focus on Cold War intrigue, but only part of the first novel, which involved characters mixed up in events in Cuba in 1956, was completed. Translator Donald Nicholson-Smith has been working on making Manchette’s writing available in English with the aid of fellow translators Alyson Waters and James Brook (you can read an interview with him about his decades-long effort here). Two of the translations were published by City Lights and the rest have been taken up by the New York Review of Books, in really wonderful editions with helpful forewords and/or afterwords that provide all the necessary French social and political context. 4.5 Serie Noire or What Do the French Have to Do With All This? Before I get more into Manchette, it’s worth explaining more about Serie Noire, the French publishing imprint I mentioned, founded in 1945 by Marcel Duhamel. What I know about Duhamel is vague, due to there not being much on him in English (the most useful source I’ve found on him, which provides a foundation for this section, is James Naremore’s “American Film Noir: The History of an Idea”), but intriguing: Duhamel had been connected to the surrealists in the 20s, the house in Montparnasse he shared with screenwriter Jacques Prevert, novelist Raymond Queneau, and artist Yves Tanguy being one of the movement’s main hangouts. As the 30s rolled around, he translated two American crime novels, W.R. Burnett’s Little Caesar and Raoul Whitfield’s Green Ice, which got him work in the film industry, translating dialogue of American films into French and appearing in character parts, including in Jean Renoir’s The Crime of Monsieur Lange from 1936. In 1944 he encountered two novels by the British pulp writer Peter Cheyney, starring Cheyney’s character Lemmy Caution. Duhamel talked to the head of Gallimard and proposed a line of crime fiction, primarily translations of Anglo-American pulp novels. That takes us back to September 1945 and the founding of Serie Noire, five months after the German surrender. Starting with the two Lemmy Caution adventures. Now, while I mentioned that at the time of Hammett’s death his books were out of print in America, in France they were available, translated by Duhamel himself and issued through Serie Noire. The French kept a number of American crime novelists in print and circulating when they’d been largely forgotten in America; read them, wrote about them, and continued adapting them into notable movies after Hollywood had moved on. David Goodis’ Down There, published by Serie Noire as Tirez sur le pianiste! in 1957, became a Truffaut film in 1960. Godard turned to Serie Noire frequently, adapting Dolores Hitchens (Fools’ Gold, published by Serie Noire in 1959, became 1963’s Bande à part), Lionel White (Obsession, published by Serie Noire in 1963, provides the basis for 1965’s Pierrot Le Fou), using Donald Westlake as a jumping off point for Made in USA (The Jugger, one of Westlake’s Parker novels under his Richard Stark pseudonym, published by Serie Noire in 1966, the same year Made in USA came out. Godard was working fast then, too fast to bother with clearing the rights to the book. Technically only the opening and closing scenes of the movie have anything to do with the book, but that was enough to keep it unavailable (legally) in the USA until 2009 outside of its showings at the 1967 New York Film Festival. Last year, I watched it streaming on the Criterion Channel app), and Peter Cheyney. The Cheyney “adaptation,” 1965’s Alphaville, was a strange case. It starred Eddie Constantine, who’d played Cheyney’s character Lemmy Caution in a number of French b-movies adapted from Cheyney’s novels in the fifties, and had him reprise his role in an avant-garde sci-fi noir adventure. It’s not actually adapted from any of Cheyney’s books but it is an “official” use of the Lemmy Caution character; if I’m remembering the account of events from Richard Brody’s Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard correctly, it was pitched to producers as an adaptation of actual Cheyney books and Godard even had an assistant write up a script based on two Cheyney books to show the investors in order to secure the money and the rights to the character, and then just went and made the movie he wanted to make. Jim Thompson was adapted by Alain Corneau for 1979’s Serie Noire, based on A Hell of a Woman, which had been published in France by Serie Noire in 1967 (for my money, it's the best film version of Thompson in any language. Experimental novelist Georges Perec wrote the screenplay(!)) and by Bertrand Tavernier in 1981’s Oscar-nominated Coup de Torchon, based on Thompson’s Pop. 1280, published in France by Serie Noire in 1966 as 1275 âmes with no accounting for where those five souls got lost in translation. Pop. 1280 was given a place of pride as the 1000th title published by Serie Noire. That they had amassed a catalog of a thousand titles in the 21 years between those first Lemmy Caution novels and Pop. 1280 seems a clear indication that there was an audience for Serie Noire. Another reason the French are so associated with American crime fiction is the name of the imprint, Serie Noire, a title suggested by Jacques Prevert. Literally translated, it means “black series,” and the books were printed with black covers and the titles printed in yellow, a design choice also suggested by Prevert that became iconic, but the phrase “serie noire” also means something like “a run of bad luck.” In 1946, French critic Nino Frank wrote an article about some recent trends in American crime films, often adapted from writers that were being translated and published in France by Serie Noire, and offered “films ‘noirs’” as a potential term for the trend. It wasn’t until the mid-50’s, though, that the term “film noir” really began to catch on following the publication of the first book-length study, Panorama du film noir américain, in 1955 by the French critics (and second-generation surrealists) Raymonde Borde and Etienne Chaumenton. Marcel Duhamel wrote the introduction. 5. Getting Back on Track: Manchette’s Novels If you’re still with me, I’ll return to Manchette, whose involvement with Serie Noire gave him a great familiarity with American crime writing, a familiarity that was filtered through surrealists, Situationists, and nouvelle vague films. The result is crime novels where the narrator will slip in declarations like this one, which closes the opening chapter of 1976’s 3 to Kill: “The reason why Georges is barreling along the outer ring road, with diminished reflexes, listening to this particular music, must be sought first and foremost in the position occupied by Georges in the social relations of production. The fact that Georges has killed at least two men in the course of the last year is not germane. What is happening now used to happen from time to time in the past.” Manchette, like the Hammett of Red Harvest, is a crime writer, not really a mystery writer, with an exception I’ll come to in a bit. Often, as in the above quote from 3 to Kill, he jumps ahead in his narration to reveal outcomes ahead of time and let the reader know that fates are already sealed. In 1973’s Nada, which I’d recommend as a starting point, the outcome is given to the reader in the opening chapter, presented as a letter home from a semi-literate cop to his mother describing his pride at the job done killing the Nada Gang, a left-wing terror cell made up of a motley crew of despairing radicals that kidnapped the American ambassador. The rest of the book takes us back through the Nada Gang’s clumsy but surprisingly (even to them) successful kidnapping plot and the subsequent crackdown by the state. When the terrorists comment on their futures, the narrator reminds the reader that they don’t have one, that their deaths are rapidly approaching. It’s clear that Manchette is more sympathetic to the terrorists than the state, but both sides come in for mockery, and ultimately he warns that “leftist terrorism and State terrorism, even if their motivations cannot be compared, are the two jaws of the same mug’s game.” In a move that may prove troubling to some readers, he doesn’t rule out violence entirely, but argues that “terrorism is only justified when revolutionaries have no other means of expressing themselves and when the masses support them.” In post-68 Europe, he believed letting despair become violence was a mistake, although in an introduction to a later edition of Nada he would later chastise himself for failing to consider that the state may, through provocateurs, create a spectacle of violence if the left refused to provide it. In Nada the spectacle of terrorism ends up serving the state, who use the ambassador’s kidnapping for all kinds of inter-departmental bargaining; in the scenes where we follow the police closing in on the gang, the biggest obstacle isn’t any measures the gang have taken but various factions within the police and intelligence agencies withholding information from each other to use as leverage (a group within the police force loyal to an official with OAS ties who was pushed out in the aftermath of Algeria, for example, sees an opportunity to restore him to power. If acronyms like OAS are meaningless to you, don’t worry, the NYRB edition will fill you in). Lest these books sound like dry political lectures that happen to include crime, I want to emphasize that, like his American models, Manchette wisely keeps his books under 200 pages, with a lot of the chapters running two to three pages, and packs them with precisely dictated and thrilling action. Outside of Nada and The N’Gustro Affair, the politics are mostly implicit and only articulated in throwaway lines. The N’Gustro Affair, from 1971, was Manchette’s solo debut under his own name, following pseudonymous work for hire gigs writing stuff like erotica and film novelizations and a novel, Laissez bronzer les Cadavres, co-authored with Jean-Pierre Bastid; it’s the most overtly political, a fictionalization of the life and violent death of Georges Figon, a minor character in the real life 1965 Ben Barka Affair, the kidnapping and assassination of a Moroccan opposition leader on French soil with the complicity of the French police; Gary Indiana’s introduction to The N’Gustro Affair does a good job laying out the known parts of a still murky historical episode. I probably enjoyed it more than the actual book it was introducing. Its shallow, smug primary narrator, an amoral middle class petty criminal with ubermensch delusions from taking a few philosophy classes before dropping out and enlisting in the army to avoid prison time for one of his violent, antisocial outbursts, is hard to spend a whole book with, even a pretty short one, even with some amusing lines like, “I’m not queer and I’m not a masochist but I must admit, to be frank, that there is pleasure to be derived from rough manhandling by powerful brutes, particularly when they are one’s intellectual inferiors.” I know I said I wasn’t going to make this about Jean Genet, and I won’t, but that’s the sort of sentiment that feels pulled directly from stuff like Querelle. It’s pretty good for a debut, but if I’d read it first I don’t know that I would have been looking to read more Manchette right away. Outside of The N’Gustro Affair’s perhaps overly thorough study of a distinctly unpleasant character, though, even a strongly political novel like Nada puts entertainment first, working as a breathlessly paced thriller with characters that argue about politics amidst all the action. Action is where Manchette really excels. His interest in “behaviorist” writing and experience as a screenwriter results in books that emphasize the physical and how the characters are navigating their environments. This never goes smoothly. Like fellow Hammett disciples the Coen brothers, Manchette includes an element of slapstick in his portrayals of brutal violence. Everyone is bumping into things, tripping, firing shots that end up maiming instead of killing. A highlight of his second novel, the chase narrative The Mad and the Bad, has a team of killers catching up with its unstable heroine Julie (she’s been pulled out of an asylum and given a babysitting job by a wealthy philanthropist even though she’s pretty sure she wasn’t ready to leave) in the middle of a crowded grocery store: “Coco came in through the glass doors. Suddenly he dashed forward. Julie whirled round. Tableware was on display close by, and she swept a pile of unbreakable plates onto the floor. They didn’t break.” It’s possible, from these sentences, to see the series of shots that would occur in a film version of The Mad and the Bad (one was made, but I haven’t seen it). Things quickly escalate from there, as the killers start firing wildly into the grocery store while Julie makes use of whatever she can grab off of shelves and display tables to fight back and panicked shoppers run in every direction. The outbreak of public violence is at once horrifying and, thanks to descriptions of unbreakable plates not breaking and “fragments of plastic toys spraying into the air along the path of [a] bullet” while “above the hullaballoo [float] the sweet yet cannonading tones of an old Joan Baez hit, piped in through the speakers,” pretty funny. It’s also pretty surreal, in the sense of Andre Breton’s declaration in The Second Surrealist Manifesto from 1929 that “the simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd. Anyone who, at least once in his life, has not dreamed of thus putting an end to the petty system of debasement and cretinization in effect has a well-defined place in that crowd with his belly at barrel-level.” As Thompson, a hitman with a stomach ailment, spits bile on the tile floor and doubles over with laughter in between gunshots that take out “commodities” and unlucky bystanders, it seems like a dramatization of Breton’s provocation. (It should be kept in mind that a key inspiration for the surrealists was the Comte de Lautremont’s celebration of evil and vileness, Les Chants de Maldoror, and that Breton was kind of a misanthropic asshole and petty tyrant.) The book’s final set piece is another piece of unnervingly violent comedy, a shootout occurring on a grassy hillside shortly after a rain so everyone is slipping and sliding across the landscape while desperately fighting for their lives. I’ve enjoyed all the Manchette novels I’ve read so far, which is everything that’s been translated into English at the moment except The Prone Gunman and the second half of 3 to Kill, which I’m currently in the middle of. Nada, as previously mentioned, is a good starting point, and The Mad and the Bad isn’t a bad place to start either. To finish this quick tour, I want to focus on No Room at the Morgue, Manchette’s spin on the mystery novel, and return to Hammett. The star of the book is Eugene Tarpon, private eye, the only Manchette character to get a sequel (most don’t make it out of their books alive, and the ones that do are rarely in any condition for further adventures), Que d’os!, which is currently being translated for the New York Review of Books. Alyson Waters is handling the translations for both Tarpon books. No Room at the Morgue is one of Manchette’s most direct homages to Hammett (not the only one, as the later Fatale is sort of a reworking of Red Harvest), laconically narrated in the first person by its private eye hero like the Op stories and novels. However, unlike the Op, Tarpon is really bad at being a private eye. When the book opens, he’s preparing to close his office and move back in with his mother in the countryside. He hasn’t actually had any cases, and his money has run out. He was a cop until he killed a protestor during the events of May 68. The events are murky, mostly due to Tarpon trying very hard not to think about them, but what we can gather is that he made a television appearance afterwards owning up to what happened and left the force under highly strained circumstances amid a moral crisis. Now, he drinks and plays at being a private detective and gets uncomfortable when people inevitably recognize him from television. Here he is, handling a potential client: “What brings you to me? I mean, where’d you get my name?” I asked, thinking it was a good question. They often ask it in American movies, even though they phrase it better. “You placed an ad in Detection.” “Yes, precisely.” I held on to the edge of the table and felt like vomiting. Yes, precisely. I got a grip on myself. When he finally does get involved in a murder case, he’s completely incompetent and it’s mostly other characters coming to his aid that enable the case to be cracked. If you’re on the book’s comic wavelength, this only adds to his charm. No Room at the Morgue is a surprisingly hopeful novel (maybe the sequel takes a darker turn, but I won’t know until it’s translated). Tarpon, despite his unpleasant past, is a well-meaning sad sack tormented by his mistakes, and he’s very easy to root for. It’s not at all what you’d expect from a radical left author otherwise critical of the state and the police. The explanation, I think, is Hammett. After all, Hammett went from a Pinkerton, working for “an enterprise specializing in the applied class struggle” as Manchette put it in an essay on “Dash,” to a committed Communist willing to take jail time instead of naming names. Maybe among the cops who crushed the protests during May 68 there could be another Hammett. Maybe not, but without a belief that people can change in ways other than abandoning idealism as they age, it’s hard to have any hope at all, and Hammett, for all his flaws, is evidence that people can change. Tarpon hasn’t undergone any major shift by the finale of No Room at the Morgue, ending it about as oblivious as he began, but he manages to do the right thing and fights against what turn out to be, in a sense, the forces of fascism, even if he doesn’t understand that that’s what he’s doing. One has to find hope somewhere, something to keep from sliding into the Nada Gang’s despair. Manchette seems to have found it in Hammett. 6. Crime Novels (Slight Return) If anyone’s facing readers’ block, well, you probably stopped reading ages ago. But if, somehow, you’re still here, I hope you’ll head to the library or a bookstore and grab a crime novel, find one of those easy, pleasurable reads and also find it has a lot more to offer. And maybe you’ll pick up The Group, or The Passion, too, and rediscover what you liked about reading. If you’re not facing readers’ block but haven’t ever read Hammett or Manchette or the others I hope you’ll add them to your to-read list and give them a shot because I think they’re great writers. And if you’ve never really given the genre a shot, I hope you, too, will be inspired to think about crime. Thank you, Elise, for the help cleaning this up (there were a lot parentheticals that went on even longer originally, among other things) and thinking through things more thoroughly, and most of all for being a friend. by Lucas Fink Rick Altman wrote about how Hollywood narrative cinema is basically structured around and propelled by a character with easily-understood motivations progressing through a series of events chained together causally. So, things like spectacle and pathos (musical numbers, action scenes, sobbing, screaming, bright colors, etcetera) are outside, are in excess of, this dominant Hollywood system. Altman offers a crucial nuance here, though: this excess is only conceived of as such relative to the system that asserts itself as dominant. The implications are that excess, secondary logics, minor positions, spaces of subversion, or whatever you want to call them are not in themselves excessive. In his words, “Unless we recognize the possibility that excess – defined as such because of its refusal to adhere to a system – may itself be organized as a system, then we will hear only the official language and forever miss the text’s dialect, and dialectic”(35).The rub here is that, if given the chance, that which is repressed by a given dominant system could very well organize itself into its own system. I wish ask if this has ever actually happened, if oppositional elements have ever been allowed to flower into a system of their own. The song “Brother Sport” by psychedelic pop group Animal Collective presents, I think, a decent approximation of such a system, a system in which the marginal becomes the dominant. The dominant’s status as such, then, is a product of contingency, and forever precarious. First, we must define the dominant for pop music. Altman here is working with film, and thus defines the dominant for film: “With few exceptions they[film theorists of the past two decades] have stressed omniscient narration, linear presentation, character-centered causality, and psychological motivation … [as well as] the importance of invisible editing, verisimilitude of space, and various devices used to assure continuity”(15). It is in reference to these dominant standards of storytelling that Altman identifies the excessive: contingency/coincidences(33), parallelism/multiplicity of perspectives(20-26), overlong spectacles, and unabashed pathos. What, then, constitutes the dominant for contemporary pop music? We can, with little research effort, determine that the vast majority of popular music adheres to the “verse A – chorus - verse B – chorus – bridge - chorus” structure, or some mild variation. It is now apparent why pop music is often said to be “hook reliant”, for the dominant structure is designed to foreground a singular catchy refrain. Everything that is not the hook/chorus then takes on a supportive role, becoming connective tissue which justifies the song’s existence as a song - as more than just one random earworm - usually via the delivery of some narrative related to the chorus’s lyrical content. Pop’s lyrical content is impressively diverse, making it difficult to explain the genre’s dominant in terms of lyrics. Whatever the song is “about” superficially, though, the lyrics almost always situate the listener comfortably in either a physical setting, interpersonal scenario, or psychological condition. Importantly, because of pop’s unswerving loyalty to its central refrain, the situation the listener finds themselves in is usually static; a given song is obligated by its structure to repeat its one refrain, and whatever lyrical content therein, multiple times. Charli XCX’s “Vroom Vroom” is about driving really fast; the listener begins the song in a fast car and ends the song in a fast car. Lorde’s “Royals” is about class resentment; the listener begins the song simultaneously fetishizing and repudiating inaccessible opulence and ends the song doing the same thing. However, just as Altman discusses the necessary presence of a counter-logic wherever there is a dominant logic(31), so too is the marginal present in pop. The verses, being the only non-repeated element of pop songs, are the marginal. More specifically, the verses’ promise of change, of a meaningful evolution throughout the song, is the marginal, even though this is a false promise. The verses exist to trick the listener into thinking the end of the song will be different from the beginning, just as unpredictable beginnings in American film exist to veil the fact that the ending will almost certainly be a happy one(Altman 32). How does “Brother Sport” systematize elements that would otherwise be subordinate/tertiary? The track engages in a wholesale jettisoning of classic pop structure such that it becomes impossible to even locate a verse or chorus. Instead, the listener encounters three rhythmically distinct hooks woven into a lush soundscape of twinkling synths and thrumming African/Latin-inspired percussion. The second hook immediately follows the first, and the last hook is separated from the others by an unapologetically lengthy chunk of instrumental phantasmagoria. The rub here is that each hook – which, in the context of a classic pop structure, would be the centerpiece of its own singular song - is mercilessly excised from the track to make room for the next. The primacy of hooks/the revered status hooks enjoy in classic pop song structure is thus wholly undermined, indeed flatly rejected in favor of an entirely different system, an entirely different operationalization of hooks. “Brother Sport” then organizes itself not around the singular, imitable, omnipotent God-Chorus, but around a rhizomatic multiplicity of catchy lyrical nuggets, none of which are afforded more ontological significance than the others. Furthermore, Animal Collective supplants the illusion of progression common to classic pop tracks by actual progression. In “Brother Sport”, the situation is an interpersonal scenario: the singer, whose father has just died, is giving his brother advice regarding mourning. Here’s the icing on the cake, though: the song, in virtue of its atypical structure, ends differently than it began, for the writers have the gall to conclude with a hook other than the one they began with. We begin with refusal of tragedy(“I know it sucks that daddy’s done but try to think of what you want”) and end with hopeful, future-oriented euphoria(“You’ve got a real good shot […] Keep it real; give a real shout out”). “Brother Sport” then affirms that, however naturalized the classical system may be, its position as such is perpetually tenuous and contingent on the subduing of its excess, excess which contains a world in itself, albeit unactualized. “Brother Sport” is this actualization of the worlds nestled in the crevices in the status quo. by Maxwell S. Zinkievich When I received my first car at sixteen and I got into the driver’s seat for the first time, my parents had already placed CDs of Björk’s studio albums Vespertine and Post in the center console. From a young age I had been attracted to her unique and powerfully realized personal drive to create and to innovate. Each album that she releases, each project that she works on, is distinctly of her own; unreproducable. I listened to her music in almost a religious sense, and before the 15th of February this year, I had yet to see her in concert. I will say very little to criticize Björk and the production of this show within this “review” of sorts; I hope that it be taken more as a discriptive account of what this queer kid experienced rather than something that one would see in Rolling Stone. While this show has received critical acclaim from a myriad of critics (Rolling Stone included) with decades more experience and credibility than myself,, I will do my best not to parrot what has already been said before; even if my opinions mirror theirs closely. In short, the production that I saw on the 15th of February 2022 held at the newly constructed Chase Center in San Francisco is a triumph not only for the production staff, show director, and accompanying musicians, but also for Björk herself. View of the set pieces and projector curtains. source: Santiago Felipe via https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/music/story/2022-01-25/bjork-cornucopia-tour-pandemic I would like to begin by examining the air that was created as the crowd entered the stadium. A floral graphic was projected on the curtain of the stage, throwing off great amounts of teal and pink light into the surrounding stands. As people gathered and found their seats, the atmosphere was unlike anything I had experienced before. People dressed up to attend this event, but not in the manner that one would expect. Sure, there was a fraction that dressed in festival wear or another light-show techno ready attire, there was even a swan dress or two. The majority of the people in attendance, however, were in formalwear. Not many suits and gowns, but that distinctly SF/Tech world of spiffy clean haircuts and slick gray shirts and pants, maybe a slightly unconventional blazer thrown in for color. Nothing insane, but a step up from the usual uniform of All-Birds and Patagonia. These people were dressing up for something, something more than a concert or live performance. They were there to witness something between the lines of performance art and a symphony—and if anything, they were underdressed. The show opens with an acapella performance from the Icelandic Hamrahlid Choir that set the mood and moment for what would take place after. Their vocals would be used onstage to back up Björk throughout the show, and play a critical part in building the soundscape. After this performance, the stage goes dark and the curtain reveals itself through movement to be a number of sheer and semi-transparent sheets placed at varying depths into the stage. These sheets would be used to catch projections that blended the digital space created by the show's technal art team. The curtains would be pulled in and out of their nooks on the sides of the stage for each track, finding a place where they perfectly work within the stage visuals and the music to build a cohesive and natural extension of the world that Björk was building onstage. Because of this digital canopy, the stage itself was fairly devoid of non-functional set pieces. A tiered system of fungi-looking platforms allowed for staging of the static musicians as well as a dance platform for the accompanying flute ensemble. source: Santiago Felipe/Getty Images for ABA via https://www.sfgate.com/characters_clone_20628_20210818162542/article/bjork-sf-cornucopia-concert-review-16836327.php Here I believe that it is important to make note of the album that Björk is primarily drawing from for the setlist of this production, Utopia. As always, Björk trends to more abstracted and unearthly lyrics and methods of composition. She almost never utilizes a chorus in her work, and breaks away from musical tropes that would make her music repetitive. Her compositions always trend more along the lines of a story or abstract emotional ballad. Utopia is, for many, a pinnacle of this style of work. I would make the argument that none of the songs that Björk plays throughout this show could be termed “danceable”. Not that she is unable to create songs that are, but that the goals that she has as an artist do not fall within the realm of making the next big hit. Therefore, if the reader were to find any recordings of this performance online, I would urge them to watch under the guise of an opera-goer. The production of the show is designed to create an immersive world that the viewer is allowed a glimpse into. One that does not exist outside of the temporal and physical space of the stage. Elaborate costumes grace the bodies of Björk and her accompanying floutists. Fashion houses Balmain and Iris Van Herpen designed the costumes of Björk herself, with elaborate face-embellishments designed by James Merry and make-up by Johannes J. Jaruraak (@isshehungry). source: Santiago Felipe/Getty Images for ABA via https://consequence.net/2022/01/bjork-cornucopia-recap-los-angeles-shrine-auditorium/ I mentioned previously that Björk is an artist who is constantly on the cutting edge of what can be done technologically for her music. She was one of the first artists to include electronic instruments alongside an orchestral arrangement on stage in the mid 1990s and has continued to push the envelope in as many ways as she can. I also mentioned that she has very few non-functional set pieces with her on stage. What she does include that for me falls into the category of functional is a reverberation chamber that was specially constructed for her voice. This physical chamber is situated in the back of stage right and adds a unique flavor to the singer’s voice for certain tracks. She also includes an instrument that she calls “water drums” which take the form of large wooden bowls and a tub of water. The player places the bowls face down in the water and beats on the convex side of the bowl. This creates a uniquely full and reverberating drum sound that is picked up with an array of microphones around the water basin. Some of her tracks require the sound of falling or dripping water which are also captured live from this apparatus. Perhaps the most unique piece of instrumentation that was constructed for this show is what I term an “orbital flute” which is a series of four or five individual silver flutes that have been connected and bent into a circular shape. This instrument stays suspended high above the stage and is lowered around Björk. Thus, when the accompanying flutists play the instrument, her vocals are emanating from a literal encirclement of vibrating, musical air. It is difficult to draw any conclusions about the experience that can be drawn out into the realm or reality. The metaphors of the album Utopia circle around creating a world that is free from a past of hate, anger and pollution. Before the encore, a recorded speech by climate activist Greta Thunburg is played to give the audience the state of emergency that the world is currently facing due to the climate crisis. Perhaps it was Björk’s goal to create a window into a world that is unbounded by these issues and to show the audience the unfathomable beauty and emotional expanses that can be seen if we band together in love to fight climate change. In closing, the show itself was transcendent of the physical world that we inhabit and is a triumph of creative thought and execution. Uniquely visionary, confusing, fascinating, creative, captivating, alien. Uniquely Björk. Björk in Balmain and surrounded by “orbital flute”.

source: New York City Photography/Santiago Felipe via https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/44409/1/bjork-cornucopia-the-shed-new-york-interview Situated along Emilia-Romagna’s eastern shores, the town of Rimini draws huge summer crowds eager to populate the modest coastal town’s seaside promenades and capacious beaches. Villas and resorts erected to accommodate the seasonal swell of imported beachgoers occupy the skylines that lie both to the north and south. But the summertime, and the profitable reverie that the city hosts, must come to an end. Who, or what, remains during the hibernal months that lock the sea under gray horizons?

Unbeknownst to many of its summer inhabitants, Rimini was the birthplace of Italy’s most celebrated director, the larger-than-life Federico Fellini, whose prolific career earned him international acclaim. His slice-of-life realism articulated incisive critiques of Post-War Italy’s social conditions, and the grandiose forays into the phantasmagorical and carnivalesque that defined the latter half of his oeuvre captured the circulating values, desires, and collective fictions of the Italian imagination. In the off-months, the legacy of Fellini has made the town of Rimini a coveted destination among devoted admirers who seek to understand the landscape that produced such a beautifully singular and singularly beautiful artist. With the support of Emilia-Romagna’s Ministry of Culture, Rimini has mobilized a considerable amount of money and effort to monumentalize Fellini and his work, much in the same vein as Bergman’s Fårö or Elvis’ Graceland. The recently inaugurated Federico Fellini Park skirts the sandy edges of Rimini’s northern beaches, a statue casts a shadow of Fellini’s likeness during the right time of day along the Marecchia, and throughout the town bakeries hotels and cafes all bear the namesake of the now deceased maestro. His ghost permeates and reinscribes the town itself: the beaches bear an uncanny resemblance to the seaside abode where we first meet Gelsomina in La Strada, the gloomy mist that drapes over the water in the late evening is indistinguishable from the blanketing fogs of Amarcord and I Vitelloni, and so on. But the implication of Fellini does not suffice. Surely one of cinema’s greatest contributors and pioneers is deserving of a more ceremonious commemoration. The most appropriate elegy is of course the viewing of the filmography itself. But such an undertaking cannot be demanded of the weekend sightseers who, perhaps unfamiliar with Fellini and his work, may require some inertial nudge. Furthermore, there is a rapacity among those who are familiar with Fellini to cultivate a deeper understanding of the spiritual and cultural underpinnings of Fellini’s life that were in turn prismatically refracted through his films. But how does one represent the animus of such a resonant and epiphanic body of work or the life of their enigmatic creator? The opening of the Fellini Museum in August of 2021 is the latest and boldest attempt to do so. The Fellini Museum is not a single location but is instead an entire environment dispersed across several buildings and public spaces. The 15th century Castel Sismondo has been reoutfitted as an interactive and immersive exhibit that functions as a cinematic cornucopia containing fifteen rooms that each engage with different dimensions of Fellini, his films, and his legacy. It is undoubtedly the centerpiece of the Fellini Museum. La Piazza dei Sogni (Plaza of Dreams), shrouded in a fog meant to recall the transatlantic voyage of Amarcord, is bordered by a veil of water that reflects the edifice of Castel Sismondo and Teatro Amintore Galli. Further along the plaza is a 17m golden, illuminated circular bench reminiscent of the circus rings at the end of 8½, a convivial public space that, much like the film, celebrates a communal solidarity and equanimity. One can stroll from Castel Sismondo across the Piazza dei Sogni to the other major indoor exhibition space, Palazzo del Fulgor, along a pathway of sound that weaves voices and music contained within (and inspired by) the films of Fellini. Palazzo del Fulgor is a historic movie theater immortalized in the film Amarcord but more importantly was the theater Fellini himself attended in his youth. It has recently been restored and screens a rotation of Fellini’s filmography as well as other contemporary releases. Palazzo del Fulgor is the most recent addition to the Fellini Museum, utilizing three floors to conjure a perennial interpretation of Fellini, locating his legacy fits in the wider landscape of film art. Next to the entrance of the Palazza is a jesmonite statue of a rhinoceros on a small boat, a reference to the film E La Nave Va and the main symbol of the Fellini Museum. The exhibitions in Castel Sismondo employ material installation pieces, projectors that fill the walls with various video excerpts, and text elements that help contextualize the spaces. Immersive soundscapes cohere the disparate elements and gestalt in a multimedia and multisensory exploration of Fellini. The contents of the fifteen rooms are as follows:

Palazzo del Fulgor’s exhibits provide contemporary reflections on Fellini, and more abstract ruminations on the significance of his films. The Cinemino is a small theater programmed with interviews with celebrated directors and film scholars that reinterpret his themes on diegetic, critical, and discursive levels, as well as other vignettes that frame the scope and magnitude of Fellini’s career. The Room of Words is a soundproof standing space with overhead speakers that project the voice of Fellini contemplating himself and his work. This abstract exhibit interlaces several audio excerpts of Fellini grappling with the meaning of his life and the significance of his efforts as a filmmaker. The House of the Magician reveals the mystical aspects of Fellini’s work, and his propensity to expand his poetic range through studies of esoteric, occultist, and mythic texts. The Moviole allows its attendees to inter-splice and remontage excerpts of Fellini films, underscoring the continuity of his craft across several decades. Attendees also have the opportunity to explore the museum’s repertoire of letters, posters, testimonies, and drawings of Fellini via the digital archives. The Fellini Museum beckons its visitors to enmesh themselves within the inestimable work of Federico Fellini and recognize that these films have unraveled the antinomies of our reality. These works bridge the divides between realism and fantasy, between the sacred and the profane, and between tradition and contemporaneity. As such, Fellini, and this magisterial space crafted to celebrate him, proffer more than intellectual or spectatorial stimulation, rather, an apprenticeship to finding one’s lust for life. by Truly Edison, Lucas Fink, Lucas Wylie, and Phil Segal PART 1: Truly on the Troubling Deficit of Horniness in Modern Film