|

by Phil Segal The Mill Valley Film Festival recently wrapped. I was lucky enough to catch five screenings, four at BAMPFA, one (Ninjababy) online.

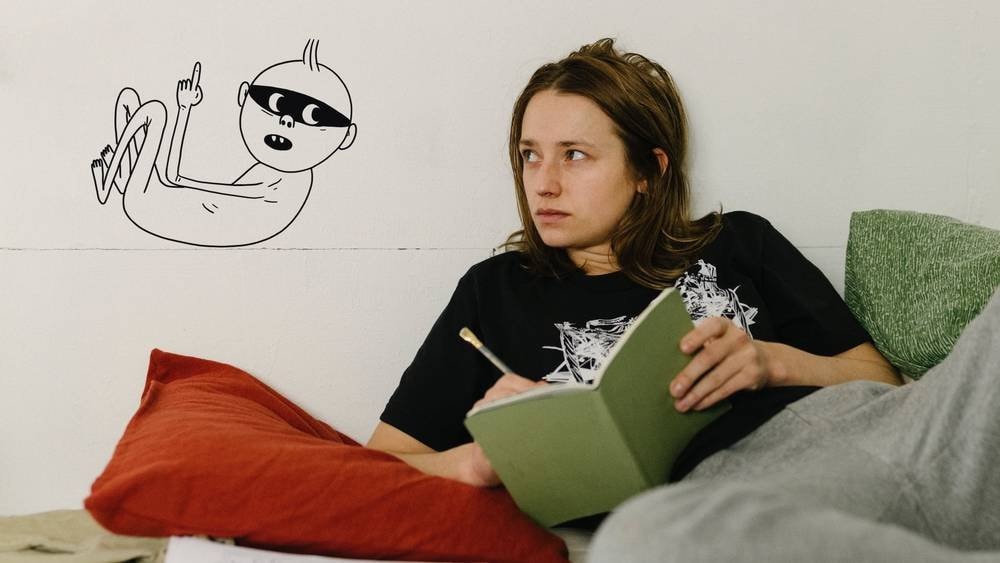

Memoria Apichatpong Weerasethakul has always been happy to let audiences’ eyes and ears wander around the frame at their leisure rather than controlling their attention (he likes minds wandering, too). Despite some worries I had about an “English language debut” featuring, at least compared to his previous work, a superstar, putting Tilda in the movie hasn’t changed anything: she’s just occasionally one of the things in the frame that you can choose to focus on, a useful tool compositionally because her body is a powerful set of lines. In the earliest days of film, shots would be composed to utilize lots of diagonals to create something visually dynamic in spite of a frequently stationary camera; frequently here Weerasethakul does the same, holding stationary shots that nevertheless keep your eyes in motion, and he has painter’s eye for arrangements of color and light as well. Even the shots that went on for minutes I felt like I hadn’t finished looking at and hearing. The purpose of shots is not to advance what little plot there is but to create visual and aural arrangements to be appreciated in the moment; if you can approach it in that way, it’s a generous, welcoming experience. Lingui, The Sacred Bonds Two sisters, long estranged, have a tense meeting in which one is unwilling to budge. Until, that is, the other sister mentions trouble with her husband, providing a catalyst for the two women to unite. This Chadian drama celebrates women watching out for each other in a world where men can’t be relied on or trusted and makes the case for the necessity of safe access to abortion. It’s well-performed, incredibly timely, and uplifting. What it isn’t is very cinematic, with veteran director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun sticking to the standard realist style of modern message pictures, but the lack of distinctive film style is ultimately inconsequential compared to what he does right with his screenplay and his handling of tone. The film doesn’t downplay the struggle its characters face or how serious the risks they take are, but focuses on resilience and resistance, resulting in an ultimately energizing film rather than the noble downer you’re likely expecting from a film about abortion rights. Ninjababy Rakel, the heroine of Ninjababy, also wants an abortion but finds out she’s much farther along in her pregnancy than she realized despite showing no signs. She frustratedly declares that it must have been some kind of “ninjababy” in order to sneak up on her like that. An aspiring graphic novelist who’s constantly scribbling on the scenes around her in her mind (one of the inventive blendings of animation and live action throughout the film), it’s not long before she’s drawn the “ninjababy,” which immediately takes on a life of its own, popping up on papers and walls to argue and make demands, much to her chagrin. Yngvild Sve Flikke’s film is an unusually raunchy, strange, and frequently hilarious look at an unwanted pregnancy, a film with characters called things like “Dick Jesus,” a sequence featuring stop-motion sperm, and one of the more charmingly irresponsible mothers-to-be in film history. In the end things get more heartwarming and sincere, and that’s all handled well, but it’s the crude and comical (in multiple senses) journey to get there that’s the original and exciting part Bergman Island Mia Hansen-Løve’s latest is another confirmation of her impeccable skill as a filmmaker. Her films are some of the most fluid being made right now; every scene ends a little before you expect it to, hard cutting the moment someone finishes talking or comes to rest, so that there’s a ceaseless momentum to her films, and the frames always include exactly what is necessary to convey information about her characters and no more for only as long as it takes to absorb that information, so that your attention is continuously stimulated and carefully controlled. It’s truly auteurism in that it creates the same effect as literary narration, the world described with a distinct voice and point of view, through visuals and cutting. An identifiable “prose” style runs through her work, the filmic equivalent of the brisk, well-constructed sentences of a Hemingway or Didion. I was slightly disappointed by what she wrote this time out, with the qualification that I’ve never had any attachment to Bergman, although as the film goes on and adds new layers it becomes more interesting. If her previous films like Things to Come hadn’t set the bar so high I would probably be more impressed by this one, which is quite good but no Things to Come. Graded against anyone other than herself, though, it’s an unqualified recommendation. Drive My Car Drive My Car is three hours long, with a narrative that unfolds in a relaxed, winding manner, and yet I never felt my attention flag or that anything Ryusuke Hamaguchi opted to show wasn’t adding to the film. A lot happens in the lives of the characters we meet over the course of the film without it ever quite feeling like a plot. The interest is not so much in seeing how one thing will lead to another; instead, it’s just what these characters will do in each situation they encounter, where their conversations will take them, because they come across as rounded people full of contradictory impulses and motives that aren’t always clear, even to themselves. Adapted (apparently loosely) from a Haruki Murakami story, the film deals with the world of theatre, large parts revolving around rehearsals for a multilingual staging of Uncle Vanya. It’s in part a film about the power of art to bring people together, to help people process things that happen to them, and to reach across time and space to speak to us. Mainly, though, it’s a film about people, the steady accumulation of detail over the three hour runtime reminding us that there are few things richer and more mysterious than what goes on within and between human beings.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|