|

by Julia Cunningham If you were single and actively or casually dating pre-pandemic, I’m sure I don’t have to

be the one to tell you that this scene was… dismal. What was already a pretty hopeless prospect(finding a supportive, respectful partner or even just a solid reliable, considerate hookup buddy) became seemingly even more impossible, as in-person dates were indefinitely cancelled and casual hookups became a potentially deadly activity. As much as I had sympathy for my single friends having to navigate dating apps and feelings of loneliness during the pandemic, I can’t lie, I was especially pleased with myself that I had been able to ~find a man~ before the stay-at-home orders began to be put into place globally. But, (spoiler alert!!) this would not remain the case, so prepare for some oversharing… NOW! As someone whose identity has been largely rooted in independence for basically my entire life, I have never felt like I “needed a man” to be complete or happy. In fact, I believed this so steadfastly that I had not so much as been on a single date by the time I arrived at Berkeley in the fall of 2019. While I realize now that that is much less unusual than I thought, I believed at the time that this fact indicated that I would, indeed, die alone. Still *intellectually* understanding that I didn’t need a partner to be happy, I figured having one certainly couldn’t hurt. And thus, with this slightly misguided mindset, I bravely set out into the vast and terrifying landscape of dating apps. Having few expectations due to the horror stories I had heard from other female-identifying friends, I wasn’t really expecting this endeavor to yield much besides a couple lackluster hookups and ghostings. However, much to my surprise, I met a guy that I actually clicked with who, upon first impressions, didn’t suck! By the time the pandemic hit, we had only been dating for about four months, but things had been progressing fast, and we had already defined the relationship and were swiftly barreling towards, *gasp*, saying “the L word.” While having to move home and make our relationship long distance indefinitely due to COVID did put a bit of a damper on things, I was remaining positive that our relationship would make it out to the other side of this pandemic even stronger. This was, perhaps obviously, not the case. While we made it through several months of the pandemic talking more regularly than ever, my move back to Berkeley in June saw a changing of the tides. The dissolution of the relationship ended up coming along as swiftly as its start, and within two weeks of us being in the same city again, our relationship had ended. Dealing with a breakup under any circumstances is tough, but dealing with a breakup during a global pandemic seemed like cruel and unusual punishment. Unable to engage with the usual post-breakup advice like “stay distracted,” go out with friends, etc., I was left to my own devices to simply think. As a person already prone to anxiety and overthinking, this was a recipe for disaster. Of course I could FaceTime friends and confide in my roommates, but the inability to simply go out made recovering from a breakup all the more challenging. While I know that it is generally ill advised to find a rebound, the fact that this was not even an option made me indescribably restless. Of course, I think that it’s important to acknowledge that there were more important things happening during the pandemic than my breakup. However, heartbreak is blind to these realities, and as much as my conscious mind was aware of and engaging with these realities much of the time, my subconscious mind was particularly fond of sneaking in reminders of now-tainted memories and self-destructive thoughts. What would, in a “normal” world, have distracted me from these thoughts were unavailable to me, and I felt like I was slowly caving in on myself due to the constant toiling and internal reflection. But maybe, what I initially thought to be my curse was actually a gift. I am in no way saying that I am grateful for the pandemic, as there is an immense amount of privilege involved in being able to thrive, or even just survive, the pandemic. What I am trying to say is that removed from the majority of activities and vices I would typically engage in in order to distract myself from emotional distress, I was able to actually feel my feelings. I don’t mean for this to sound super ~out there~, but I mean it! So much of the time, we are inclined to distract ourselves in order to avoid feeling any negative emotions. Sometimes, this approach is completely necessary for self preservation. But once we know we will survive whatever emotions we’re experiencing, it is important to engage with our feelings and explore them. Distraction is a great way to make it through the day, and there are certainly days where my mental health does not benefit from deep reflection, in fact it would be made worse. However, what I did find is that the relative stillness of my life in quarantine allowed me to be acutely aware of my emotions in a way that I am incapable of escaping. This meant that I truly had to face and resolve my problems instead of turning a blind eye and hoping they would go away. While I would honestly have been much happier to do the latter, being forced to face myself actually enabled me to grow at a greatly expedited rate, honestly learning more about myself in a shorter period of time than I ever have before. While many of the things I’ve learned about myself I’m not *the biggest fan of*, realizing these things now, unable to run from them like we humans are often wont to do, I am able to reflect on them, heal, and grow. While maybe it didn’t have to take a breakup and a global pandemic for this to happen, these events definitely sped up the process of self-discovery and self-growth for me. So, what was the point of me oversharing about my life to the loyal BAMPFA SC blog readers? Well, I guess I wrote all of this to say that times are real shitty right now (but you already knew that). And certain circumstances can make them shittier (a breakup being the least of the difficult experiences that people can be going through right now)! But, if you have the mental and emotional capacity for it some days, I would highly recommend leaning into that which is uncomfortable to explore, and exploring it. I don’t mean to sound like the author of a cheap self-help book, BUT, I will say that I know that many of us Berkeley students are particularly good at burying our noses in work in order to avoid reflecting on anything truly difficult. But enough with that! We owe it to ourselves to genuinely work on doing better, and not just running away. We won’t always succeed, but why not try! I’d like to say I’ve come out the other side, flipping my hair and thriving, but that’s not the truth. The truth is that I know way more about myself than I did six months ago, and this has been for both the better and the worse. But it has also allowed me to branch out and feel more free and connected to myself than I have in a long time. So, I guess I’ll leave you with the advice to resist leaning into distraction, and embrace the emptiness of our current social lives as an opportunity to learn more about yourself! And to tie it all in a pretty little bow, here are some particularly pertinent Little Mix lyrics that I’ve been vibing to lately: “Shout out to my ex, you're really quite the man/ You made my heart break and that made me who I am.” !!!

1 Comment

By Katherine Schloss Let’s talk about one of my favorite shows and why it should be yours, too.

What do you usually look for in a romantic partnership? A quick wit and dashing good looks? Watching The Amazing Race has made me realize that there’s so much value in someone who doesn’t piss off taxi drivers, has a stomach of steel, and, most importantly, can drive stick shift. The Amazing Race is a reality television show that has been kickin’ it since its initial airing in 2001. Teams of two race around the world in a series of pre-planned adventures. Each leg of the race contains a series of clues that the teams must find, which then direct them to various tasks such as Roadblocks (tasks which only one team member can complete), Detours (here, teams must choose between two tasks), the occasional Fast Forward (if a team completes this before any other team, they can go straight to the end), and finally to Pit Stops which signify the end of each leg. As the show developed, producers added more twists and turns, making adjustments each season to keep fans and contestants alike engaged and guessing. For example, Yields (in which one team could yield another team, forcing them to wait until the sand had run out on an hourglass before they can complete the task at hand) would later become U-turns (where the first team to reach it can force another team to go back and complete the other task option for a Detour before they can continue on). Each episode is hosted by a calming New Zealand television host: Phil Keogan, who reminds audiences that the teams need to find the perfect balance between “brains, brawn, and teamwork,” in order to win the million-dollar prize. I’m truly jealous of Phil’s rad choker necklace and laid back button ups in an ever-revolving series of earth tones. Aside from Season 26, where the producers tried something new and paired some contestants up with other contestants that they’d never met before, essentially sending them on blind dates that could last up to a month, teams are made up of people with existing relationships. It is fascinating to watch these connections play out, especially in the realm of romantic relationships, as some teams are made up of fighting married couples while others are young people that have only recently started dating. It’s a sort of a new experiment each time. Producers map out the race a month out from the time that filming starts, and casting takes months as well. When scouting locations, the production team has to keep in mind any political conflicts that are brewing, as well as the fact that natural disasters can strike, requiring back-up countries and alternative tasks to be planned out as well. I think any reality television that showcases “ordinary people” is extremely powerful. Despite the fact that there is sometimes an overlap of contestants from other reality shows such as Survivor, The Amazing Race makes an effort to provide relatively unknown characters with the opportunity to travel the world and compete for a large chunk of money. This results in a lot of unfiltered reality gold for viewers. Something that impresses me every time is the way that the camera crew is kept concealed so that viewers feel like they are the camera themselves, traveling with the teams every step of the way, whether it be scuba diving in vast oceans or jumping off of bridges. Sure, inevitably, you’ll catch a glimpse of cameramen here and there, but the only time that I’ve seen a cameraman’s face so far is when Brian and Greg, a hunky brother duo, accidentally flipped their jeep on a dirt road in Botswana and their cameraman was injured. During quarantine, I’ve been throwing it back to the early 2000’s and nostalgically watching old seasons. While the show certainly still holds up, it’s really interesting to analyze the early seasons from the perspective of travelling in a world that was freshly post-9/11. Watching this show during quarantine has made me as sure as ever that I will continue to prepare for future travels. It’s trippy to watch couples take multiple plane rides in one day, haggle with taxi drivers, and sleep in the middle of the desert when I have barely left my own bubble. I’m sure that it will be a truly out-of-body experience the next time that I travel, but I really do hope to immerse myself in other cultures ASAP. To say that we rely on our phones would be an understatement. I admittedly can’t remember the last time I had to use a physical map. If you were to be dropped off only in countries that were foreign to you, would you be able to make your way home? In these early seasons, many teams didn’t learn new languages or research other cultures before embarking on the race as later teams would go on to do. This results in a lot of requests that their taxi drivers speak English to them, and many teams end up exasperated. Maybe I’m biased, but it seems like a good strategy to learn a few simple words in more predominant languages such as French and Mandarin in an attempt to meet the taxi drivers halfway. In the way that reality shows often do, I’m sure that there is some spin that goes into editing in order to make the winning team look good. However, I feel that The Amazing Race often shows couples just as they are. Freddy and Kendra who (spoiler!) won Season 6 didn’t hold back in their bigotry. Comments such as “I feel very unsafe. I feel… we’re in the middle of ghetto Africa,” and “This city is wretched and disgusting, and they just keep breeding and breeding in this poverty! I just can’t take it,” set off more than a few red flags for me. Freddy would go on to completely lose his temper on the other teams when a steel grate crashed down on his head. Infighting is not uncommon in the race, but his anger was completely misguided, as no other team was anywhere close to him when the supposed tragedy occurred. His “One of you, I’m gonna break in half,” and excessive yelling showed how some teams crack under the pressure. I appreciated that the editing team let viewers watch as the couple experienced culture shock at every turn. On Season 5, my favorite team was cousins Charla and Mirna who emigrated from Syria to the United States at a young age. Charla had a form of dwarfism and wanted to show both American viewers and herself that she was just as capable as the other contestants. I was saddened to watch as other teams wrote her off from the get-go, calling her a “midget” and always displaying such disbelief that her team was so strong. Teams are constantly asserting that the race is, “Really anybody’s game,” but I feel that this grossly underestimates the physical and emotional challenges that the contestants have coming into the game. I’m continuously impressed by their ability to march on because of these setbacks rather than despite them, as many duos seem to have something to prove in the best way possible. The Amazing Race also shows a lot about the toxic dynamics that can exist in romantic relationships due to ingrained sexism. Example one: Johnathan and Veronica. Johnathan was a short man with a fiery attitude. He loved fast cars and dyed the underside of his hair bright blue. Throughout Season 6, I would cringe every time he yelled, “COME ON VERONICA!!!!!!” He even took to shoving her when they were beat-out to the Pit Stop, and she began sobbing uncontrollably. Later, she got injured in a subsequent Detour, and our fav Kendra yelled at Johnathan for actively ignoring her cries. Example two: Ray and Deana. Ray was a real pain. He seemed to take a page out of Johnathan’s book, berating Deana whenever things didn’t pan out as planned. I took issue with the way that he told her that she lacked a confidence and drive that he saw in himself because it was clear to me that she was doing her best to perform tasks while also dealing with a team member who couldn’t stomach the idea of not being THE BEST. He also tended to take out his insecurities on Meredith and Gretchen, a sweet older couple. He called them “sacrificial lambs,” and couldn’t seem to comprehend that they actually were far stronger human beings than he was in the long run. “I can’t be behind the old ones,” he says, “This isn’t their place.” Example three: Adam and Rebecca. They were described as an on-again, off-again couple. Adam lived at home and Rebecca tired of “babying him” and having to “run things.” Other couples commented that they felt bad that Adam couldn’t stand up for himself. From my vantage point, the relationship seemed to be toxic on both sides. Rebecca would taunt Adam for being a “sissy.” A particular road block comes to mind where Adam had to drag heavy buckets of salt out of the water. Female competitors were working much faster than he was, and Rebecca saw that as an opportunity to establish herself as the supposed “pants” in the relationship, saying, “Never send a woman to do a man’s job.” Not only does she consistently look down upon him, the relationship is clearly not healthy or sustainable, as every time Rebecca tries to tell him that it’s not working, he threatens to throw himself out of moving vehicles. Example four: Ron and Kelly. Ron was a former prisoner of war, and Kelly was a pageant queen. With this duo, Kelly’s emotional side was treated as weak and a “woman thing.” Ron complains that, when he was an army man, he was able to do whatever and say whatever he wanted. He sees Kelly as the old ball and chain that signifies his “inevitable future” of settling down and becoming boring. Ironically, Kelly would continue to return to India in the coming years for nonprofit work (no longer accompanied by Ron, who I’m hoping she ultimately made the decision to ditch). How incredibly offensive that Ron acted as if dealing with Kelly’s existence as an emotional being was a burden to him. His, “Good job woman,” isn’t just a silly little comment, it reflects an ingrained sexism and the lasting effects of his time in the biggest boy’s club: the army. I appreciate The Amazing Race for the way that it presents other cultures in a completely balanced way. The show encourages the viewer to analyze their own reactions as a bystander, watching the way that these random Americans make their way through crowded streets in developing countries (by Western standards), and asking them to question whether they would conduct themselves similarly. It’s a lesson on what sleep deprivation, fear of the unknown, and the possibility of a great fortune can do to one’s sanity. It tests relationships, forcing couples to be together 24/7, suddenly unable to ignore where their partnerships are “lacking” (it’s like the pressure that quarantine puts on relationships, but with a constant change of scene). I also commend this reality television show for unabashedly casting gay couples, elderly couples, and other pairings that perhaps weren’t as honestly represented at the time in an effort to show that the human experience is varied and that people are capable of looking normalcy in the face and spitting on its neck. Applications to be my partner for The Amazing Race will be opening once I finish grad school. Only apply if you’re ready to provide that sweet sweet ~mind, body, and soul connection~. And be willing to skydive for me, because I’m not about to throw myself out of a plane with the kind of luck we’ve been experiencing this year. by Beck Trebesch ON3P 3 is a short ski film featuring skiers sponsored by ski company, ON3P. It sets at Mt. Hood, OR and features the talents of Jens Nillson, Magnus Graner, Jake Mageau, Forster Meeks, Siver Voll, Ian King, and more. It was released in late 2018, free to watch on the internet.

The first 30 seconds of ON3P 3 spark an unsettling tension in the viewer: an old radio/television host describing the location of Mount Hood, Oregon. His voice distorts low and high over haunting horns and wailing synths. It’s eerie. This opening sound collage is paired with dimly lit landscapes of the Oregon Cascade range and skier Forster Meeks’ face emerging from the darkness as if he’s about to tell a ghost story. Intended or not, it’s highly reminiscent of The Shining (1980), the landmark horror thriller set at Timberline Lodge (on Mount Hood :0). Throughout ON3P 3 (2018), Mt. Hood itself is portrayed as an epic, mystical, and undeniable natural force. The way director/editor Jens Nillson isolates shots of Hood shows a fascination, maybe even an obsession, with the mountain that can only truly be appreciated by visiting the peak. There is inherent power in the mountain’s existence, from a spiritual and recreational perspective, exerting itself over our rag-tag group of protagonists. In one light, the skiers, the filmers, the Windells establishment, are all transforming the mountain’s dirt-speckled glaciers into features of their own creative prospects (my favorite of which being the jump to butter/manual pad). You could say park (terrain park) skiing is of the built environment, that it detaches from the sport’s more humble and earthy roots. However at the same time, shown by the countless cuts to the terrain, landscape, geology, wildlife, and more, there is a supernatural mystique of this place that captivates the mind and spirit, no matter the activity. Now, reverence for the mountains, for the natural world, is not a foreign concept in ski movies; it’s a common motif across all productions. There’s probably hours upon hours worth of B-roll that exists of skiers just looking up at the mountains and going “ahhhhhhhhh, nice, cool.” In ON3P 3’s avoidance of direct exposition, there is a silent bow to Hood and the opportunities it provides. In this light, ON3P 3 is a clear marker of more abstract, raw, and fluid filmmaking that hinges less upon the narrative of the making of the film or the cast of characters, and more on the visual and audio appeal of what you’re seeing at any point in time. A clear antithesis to ON3P 3 would be a Warren Miller ski movie. Dating back to the 1960s but still remaining culturally relevant into the 2000s, Warren Miller movies follow a formula of exposition - brief action - conclusion - repeat. They went there to ski. They ski. Then, they went there to ski. And then, they went over there to ski! What a great season! It’s pretty antiquated and bleh, but that’s not to say the concept of the ski movie and the technical showmanship of the skiing itself set forth by Miller wasn’t groundbreaking for the industry. Emerging from this were slightly less commercial, independent ventures such as TGR (Teton Gravity Research) and Level 1 Productions who took the same travel-ski formula but put the focus on the skiers and less so the grandeur of the narrative. Level 1 in particular is responsible for exceptional creative leaps that would push skiing and ski filmmaking to new heights in the 2010s. Their films, Partly Cloudy (2013) and Zig Zag (2018) are probably my favorites of all time, no cap, on god. The opening shot in Zig Zag (2018) makes me go full 🤔every time I see it. However, that doesn’t mean I don’t have my reservations about the seasonal, live venue, for-profit ski movie model as a whole. I think to sort of retain a broad audience these companies (Level 1, TGR, MSP, Field, etc.) have to present a product that’s accessible and recognizable, usually producing similar timbres across films. Level 1 is playful and creative, TGR is kind of stoic and grounded, MSP has explicitly comedic segments. This is a result of companies working with skiers, filmers, and editors that fit their mold and that the audience can identify with after they’ve seen one or two films. There’s nothing wrong with this and I love these movies all the same, but where I think ON3P 3 is truly innovative, is its raw, almost formless presentation of skiing. Aside from the opening credits where the names are presented in a list and the song changes that may or may not indicate a new segment, ON3P 3 is a non-stop back and forth of tricks, reactions, visual art, dancing, and video blogging. This distinction takes Nilson’s masterpiece out of the purely ski realm and connects it to skate culture. The parallels between Melodi skate crew’s ff part and ON3P are immediately noticeable and numerous. As someone who consumed at least 2 hours of skate parts per day in my recent quarantine, I can identify that Jens Nillson’s creative process was inspired by skate edits. Specifically, I want to focus on the overlay of videos in Melodi and ON3P. I don’t know where this practice originates, but cutting between scenes with one video then abstracted by a smaller video in the center of the screen can instill the viewer with subliminal messages, 😳, but even more so, add to the attitude of the film and contextualize the style, finesse, and power of the athlete. In Melodi, this manifests as anti-police, anti-America messaging blinking over the urban landscape of New York as the skaters dodge security guards and cops with rebellious teenage bravado. In ON3P, it adds a sense of serenity, motion, and beauty, furthered by the fantastical setting of the Mt. Hood glacier and the alpine forests. In both edits, one might extract a distinctly hip-hop/punk attitude, apparent in the style of skating and skiing. It’s not perfect. It’s rough and tumble. It’s flowy, it’s daring. Their clothing, the song choices, all of these creative and vibrational nuances of counterculture are born out of the volatility of the zeitgeist that is the internet age. In its purest essence, ON3P 3 is a celebration of what it means to be a skier. Self expression and style. Comradery and community. Danger. Peace. All of these coalesce in a striking and mind-blowing short film that I’ve revisited probably 30 times since it’s dropped in late 2018. I would recommend everyone to do the same!!! link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHRrprmA6rI&t=514s&ab_channel=ON3PSkis by Akshata Atre I “quit” social media a while ago. I mean, I didn’t quit entirely. It’s actually kind of impossible to do that if you’re a college student who wants to at least maintain the appearance of having a social life. But I still scrambled all my Instagram passwords, blocked Twitter, and only used Snapchat back in freshman year (of college) for maybe two months. But I’m still unfortunately bound to my Facebook account. I just can’t find a way to not have one and remain even somewhat in the loop. I did delete the app (the main one and messenger), unfollow all the people I’m friends with, and remove a ton of my page “likes,” though. Yet, even with all those measures in place, I still get that dopamine rush when I do login and see that I have a notification, even if it does turn out to just be someone’s birthday. Something about those red bubbles with tiny white numbers in them just inadvertently triggers that response in me-- and I really, really hate it.

The most frustrating thing about the whole situation is that, of course, those red bubbles are designed to elicit that exact emotional reaction. That’s the whole point of them. They’re meant to get you to log onto the site or open the app and scroll. And scroll. And scroll. And for what? Not to sell you products, but to sell you. Your attention. And that’s a distinction that’s made clear in the new Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. In the film, a group of former Silicon Valley tech executives & other experts dive into the inner workings of Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and the like. One of the key takeaways from the film is that the algorithms that run these platforms are a) programmed to have an outcome that is directly linked to profit; b) trying to do everything they can to keep you using the app/site longer in order to achieve that profit goal; and c) not even fully understood by the people who made them anymore. That second point that really stuck with me throughout the film, particularly when it was dramatized in one of the several scripted storylines presented in the film. In this storyline, the algorithm is portrayed by three men behind a screen who are feverishly trying to maintain the main character’s attention in order to win “bids” from various companies who want to put advertisements in front of him. We see how they use increasingly personal push notifications to draw him back into the app. Then, once they get him back on the app, they start pushing extremist political content into his feed, sucking him in even further. This story, although depicted in kind of a cheesy way, is not far from the truth. We’ve all heard about how terrorists are using social media to recruit people, and even how YouTube’s algorithm pushes increasingly extremist content the further down the rabbit hole you go. The latter is of course a great example of how this desire to increase engagement (which is essentially the point of an algorithm like YouTube’s) can lead people to content that is largely opinion-based and nonfactual. This essentially means that we no longer share a common understanding of what truth is. Because we’re not all getting the same information when we open Google. The algorithm literally prevents that from happening-- if we see the truth, we’re not always going to like it. And the algorithm doesn’t want that. It wants us to like what we see. So it shows us things we already agree with, regardless of whether or not it’s true, playing into our confirmation biases and keeping us scrolling, scrolling, scrolling, all the while collecting information that allows advertisers to target us so directly it’s scary. And the longer we scroll, the further we’re split into right and left, the lonelier we get, the sadder we get, the more anxious we get, and the further we get from reality and truth itself. So back to the first point about algorithms-- why are social media companies allowing their algorithms to push this kind of content and manipulate us this way? Profit. Their whole business model is based on finding ways to get your attention and then selling that attention, your attention, to advertisers, who are essentially funding these platforms. But it’s really more than just your attention; as Jaron Lanier puts it in the film,“it’s the gradual, slight, imperceptible change in your own behavior and perception that is the product.” Think Instagram influencers, extremely targeted ads, and the like. You don’t even realize that’s what’s happening half the time. And that is worth SO MUCH MONEY. Money is what this all comes back to at the end of the film. These companies are making so much money that they have no reason to stop these out-of-control algorithms, to stop collecting our data, to stop selling us. A corporation (contrary to the infamous Citizens United case), is not a person. It has no conscience. It’s not going to make ethical decisions for the sake of being ethical. The only way the machine will stop is if it’s forced to because of a monetary penalty or incentive. Regulations, taxes, changing the stock market so that it’s not a short-term quarter-over-quarter growth system, these are all solutions presented by the people interviewed in the film. And these options (excepting the third) have, in fact, worked in other industries. Until those larger systems change, tech companies aren’t going to make any changes themselves. And those systems won’t change unless people demand that they do. As many terrible things as there are going on right now, I really believe that this is an important issue to address. Because so long as we as a society can’t even agree on what is actually happening, what the truth is, we are never going to reach a solution on any of the many pressing issues we’re facing. You can’t build a car if half your designers think they should be building an airplane and the other half think they should be designing a submarine. And you can’t address climate change, discrimination, or economic inequality if people don’t even agree that they’re real. Thankfully, the interviewees in the film do offer a variety of actionable solutions at the end of the film, which I won’t list out here because I highly recommend you watch the film yourself. But what I would like to share are a couple stanzas from Bastille’s latest song, What You Gonna Do???, which came out in July of this year. As usual, their words are as poignant and timely as ever. "Shake, rattle and roll / You got control / Got my attention / Make me tap and scroll / You got control / Got my attention Listening, you got us listening / So what you gonna do with it? / You got us listening So what you gonna do? / Now, what you gonna do with it? / Make me paranoid / Love me, hate me, fill the void / What you gonna do with it? / So who am I? You decide / Inside out, you read my mind / What you gonna do with it?" And since we can’t all get in the faces of tech CEOs to ask them this question, watch The Social Dilemma (and maybe also read The Circle and reread 1984) and then do what you can to stop being a product and find the unfiltered truth.

by Lucas Fink

Abby Tlou2 GIF from Abby GIFs

I put down the controller and watch, hypnotized and shaking with anxiety, as the early-20s woman I’ve been playing as for the past 5 or so hours struggles to keep her toes on the bucket beneath her while the noose tightens around her neck. This is Abby. Her face, veins bursting forth from her forehead, is dimly illuminated by the warm glow of a burning car nearby. Another woman emerges from the dense redwood forest just beyond the car, lifts Abby’s shirt to reveal her stomach, and holds a knife up to it: “They are nested with sin”. These are the Seraphites. Before she can disembowel Abby, two men drag a young Seraphite girl into the clearing, whom, at the behest of the woman, shatter the girl’s arm with a hammer. An arrow then flies out from the foliage, followed by another, killing the two men. While the panicked woman shoots blindly into the forest, Abby sees an opportunity and wraps her legs around the woman’s neck. The girl with the shattered arm picks up the hammer and digs its sharp end into the woman’s eye. Abby removes her legs but now hangs freely, suffocating. A Seraphite boy with a bow-and-arrow runs out from the forest, whom the girl orders to cut Abby down. Abby collapses to the pavement, stands up slowly, rips the hammer out of the dead woman’s eye, and turns toward the treeline, from which demonic shrieks echo. “The infected are coming”, whispers the girl. “Stay behind me”, Abby orders. The camera, never having been interrupted by a single edit during this cutscene, centers itself behind Abby, and now, with no transition between the cutscene and gameplay, I’m playing as Abby, about to fuck up some mushroom zombies with a hammer. This is The Last of Us Part II, a video game written by Halley Gross and Neil Druckmann, directed by Druckmann, developed by Naughty Dog, and sequel to what is widely regarded as the best narratively-driven video game of all time, The Last of Us. The game follows a 19-year-old woman named Ellie on her brutal, increasingly hellish quest for revenge amidst a post-pandemic United States. Abby is also in the game(saying more would be a mega-spoiler). The game is really good. So good that I felt compelled to write an excruciatingly detailed summary of one of the game’s most riveting, and grisly, set-pieces. This grisliness, this shocking and often upsetting violence, has stoked significant controversy. In the first TLoU, protagonist Joel’s path of carnage never really feels unjustified up until the climax(the best final act of any piece of media ever), as both his life and that of a 14-year-old Ellie, who’s immune to the virus and potentially the key to unlocking a vaccine, are at stake. Furthermore, the game goes to great lengths to make the combat gameplay feel incredibly uncomfortable and gruesome; when you shoot an enemy with a shotgun and hear their bubbling, sputtering gasps as they hit the floor, you wince and shift your weight on the couch anxiously; you don’t scream “hell yeah epic gamer moment!!!”. In the second game, though, each murder Ellie mercilessly enacts is entirely avoidable, and Naughty Dog ratches up the violence’s gritty, disturbing realism to such an extent that I at multiple points ended up putting the controller down and refusing to play while I paced around my living room to re-center myself. When you kill someone, their friends and loved ones will cry their name in anguish. When you stealth-kill a dog with your bow-and-arrow so it doesn’t sniff you out and reveal your location, you’ll hear an absolutely GUT-PUNCHING whimper and its owner will turn around and cry “LUCY!”. I could go on. I’ve heard criticisms that (A)the game is nothing other than a miserable, guilt-ridden slog through the darkness of humanity’s heart, that (B)the game just “wags its finger” at the player the entire time making you feel guilty, and that (C)its theme amounts merely to “revenge/violence bad”. I’ve also heard criticisms made by reactionary, misogynist assholes who think “Abby’s biceps are unrealistically big” and “queer folk shouldn’t be in this game because games should be apolitical ”; these should be immediately thrown out the fucking window. I’ll engage with the former set of grievances because, while I disagree, they are actually substantive and interesting and warrant a meaningful response. Firstly, the game is not a miserable slog. The horrific, absolutely gutting moments of tragedy and violence are far from the only content the game presents; countless funny, beautiful, and serene respites populate the narrative. Gross and Druckmann don’t brandish carelessly the emotional weapon of tragedy and violence; they use it sensitively and selectively. Secondly, “the game” is an abstract, inanimate noun; a text can’t “wag its finger at the player”. If anything, the game is wagging its its finger at its central characters; they are the perpetrators of these atrocities, not the player. The player is just along for the ride. I can understand, though, why it is so difficult to distance yourself from or to assess unbiased by empathy a character when you control most of her physical actions. The game, though, only allows you to control how the violence happens, not what happens or who gets killed. Often, the game even denies the player control over the how and just presents a small on-screen prompt: “press square to strike”. Naughty Dog didn’t set out to make a role-playing game and as such afford the player absolutely no influence over the game’s events; that’s the point. They’re telling a linear story here via an interactive medium. Thirdly, to argue the writing is lazy because “revenge bad” is the only thing the game has to say is wildly reductive and short-sided. Even if that singular message is the only thing the game communicates, who cares? Classic works of literature and film often boil down to absurdly simple central conceits, not to mention that there’s a vast reservoir of widely-loved texts for which “revenge bad” is really the only theme(Moby Dick, to mention one). TLoU 2 is about identity, perspective, nature and humanity’s existence within and/or apart from it, understanding the Other, cycles of violence, and, yes, revenge. I could’ve just written on all those themes, which probably would’ve produced a more original and insightful post, but a rant in defense of the game is probably more fun to read and I’m at 1,000 words. I'll totally lend you my PS4 so you can play this game. By Saffron Sener At my best, I have between nine and thirteen rings adorning my fingers. This collection has developed since the day I realized that although my mom rebukes the wearing of jewelry, I, as a person separate from her, canin fact wear it anyway. My collection is vast and highly varied; from that which you accumulate from toy dispensers at pizza parlors to my prized $25 opal band, my fingers have worn it all. Although I have amassed hundreds of rings - the horrible ornamental things of my experimental middle school days, my now-refined silver bands and signets - there remains one type of ring I admire the most, yet never have had the pleasure of wearing: a posy ring. A 16th century posy ring, inscribed with “un temps viendra” (exterior) and “mon desir me vaille” (interior). Of course, my greatest impediment to owning a posy ring is the simple fact that they are from a bygone era and place: early modern Western Europe. Sure, I could certainly obtain a modern version - if it were not for the hundreds of dollars that endeavor would cost me. Even more cash, though, if I wanted a genuine medieval relic; on the low end, approximately $2000 would get me a “late medieval gold posy ring”. For those who may not know, a posy ring is a ring (surprise!), often a simple band of gold, inscribed with a posy, or rhyme. The inscription can be on the outside or inside of the ring, though most I have come across boast the more secretive rendition, with the engraved rhyme on the interior of the band. They were a late medieval, early modern phenomenon, most popular from the 15th to 17th centuries in England and France. Though I mainly associate them as being tokens of affection given between lovers, they could also signify gifts of respect or prestige (especially in examples where the rings have been encrusted with a jewel of some sort). There is something about this alliance of text and ring that is endlessly appealing to me. Of course, the ravenous historian in me loves that they’re historical objects I would happily wear now and use (and abuse) as a means to make every conversation about my personal historical interests. But, as a writer, and as someone who has often found a certain poignancy in text that I fail to reach in spoken word, these little posies simply radiate tenderness and passion. You wouldn’t go through all the trouble of inscribing a gold band with a few words of rhyme if you didn’t resonate wholly with those words. Especially when you consider that many rings were inscribed on the interior, and thus were not an immediate or obvious display of wealth; rather, they were a personal message, passed between individuals bound by a golden band gracing one of their fingers. Perhaps they feel so meaningful because their message is hidden, tucked beneath a ring of gold. Or maybe it is the action of those words existing against your skin, directly in contact with your person, your body, pressing against you with no barrier, no boundary. The words are truly yours; they are tangibly connected to you every moment the ring is on your finger. Oh, how I swoon. 17th or 18th century posy ring, inscribed with “Many are the stars I see but in my eye no star like thee.” Beyond the ring’s basic construction, though, are the words. The ring carries with it not just the inherent value as a luxury item, a gift, but the added significance of text. The gifter offers not only an extravagance, but the ultimate romancing: a line of poetry. Like a lock of hair, or a wallet photo, a bit of that person is with you, but even closer - their words meld with your body as something that you wear, perpetually hugging your finger. At a posy ring’s base, the meaning is derived from those words or symbols engraved upon it. Otherwise, it’s just a band. Arthur Humphreys’ 1907 A Garland of Love: A Collection of Posy-Ring Mottoes catalogues an alphabetical list of just what the title says. Some are swoon-worthy, while others feel nonsensical in our modern age. They are just a few words (limited, of course, by the size of the band), yet feel so personal, so purposeful. I have collected a few of my favorites below:

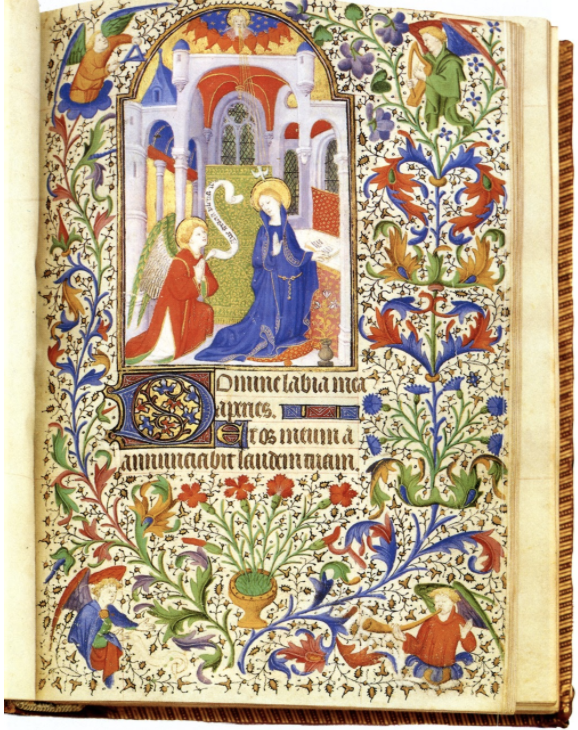

On a broader note, I admire the medieval tradition of integrating text and art. The concept of merging word and visual culture or art is typical of the early modern Western world. You can see it in paintings, as well; Fra Angelico’s 1450s Armadio degli Argenti, a set of nine panels depicting Jesus’ life, is bordered by Latin text explaining the corresponding scene of each panel. Illuminated manuscripts exemplify the ultimate medieval combination of text and image. In a more playful way, Jan van Eyck signs “Johannes de eyck fuit hic,” or “Jan van Eyck was here, 1434,” on the wall of his Arnolfini Portrait. A page from a French illuminated manuscript, the Book of Hours, dating to 1410. Notice not only the words below the illustration of the Annunciation, but the strip of text within the image as well. And, of course, the beautiful, colorful natural decoration filling the page! Considering its era, the inclusion of text proclaims something unattainable to most: literacy. The ability to read in your vernacular, be that English or French (although there is the occasional Latin inscription) was reserved for certain classes - those who could afford education and those who were educated by the church. With the innovation of the printing press in the 15th century, the accessibility of text as a mode of communication between the greater populus of Western Europe certainly expanded. But was the common farmer or barkeep reading through publication upon publication to locate the perfect line for their sweetheart? Likely not. Even more unlikely when considering the cost of gold and the expense of inscribing it. So, this was a fashion of the rich - unsurprisingly, and somewhat disappointingly. I want so badly to imagine two commoners in the English countryside, dressed in bonnets and tunics, sneaking about and sharing their secret affections tucked away behind the bands on their fingers. I want to think of them romancing each other by candlelight, creating poetry out of their love and feeling the need to capture it in the valleys of a ring’s engraving. Of course, this idyllic image is shattered when I remember their sense of hygiene, or lack thereof, and what it would be like to be a commoner or a woman or generally a person in 15th century England. The magic of the posy ring remains, though. What would I want on the posy ring I’d give to my partner? You set my heart ablaze, forever and always. A 17th century posy ring, engraved with “trew love is my desyre.”

by Lucas Fink pc creds: a Lucas sobbing in the middle of Work Song I get it; shit got crazy and you were nearly deafened when Tyler finally played Who Dat Boy. Now, having committed you and your friends’ hysteric screaming of “WHO HIM IS?!” to digital memory, that experience is re-visitable. Re-visiting is super cool; scrolling back through your camera roll to find that one video is fun and reveals the nuances of the moment that would’ve been lost to time. You can hear your phone’s speakers falter and hiccup as they attempt to regurgitate those smothering 808’s; you can remember the guy who elbowed you while moshing; you can, to an extent, re-experience the moment.

That's all well and good. What I take some issue with, though, is the commodification of memories that the digital realm encourages. I don’t like how social media transforms experiences into products, into mere things to be bought and sold. This phenomenon is specific to late capitalism and has been explained by many smart people - like Mark Fisher, Don DeLillo, and Jean Baudrillard. I’ll try to apply their analyses to those Snapchat stories of concerts you have to hurriedly tap through. Capitalism is really good at turning everything in the world into things that can be bought and sold and into spaces in which buying and selling can happen, and could not give two shits as to whether or not whatever it happens to be commodifying is a papaya or a human person. Deleuze and Guattari call this tendency deterritorialization, the process by which territories once considered sacred - like the human body - are stripped of that sanctity so the territory can be exploited to generate profit. Eventually, capital ran out of physical spaces and things to convert into markets and commodities, so it found new territory into which it could expand: the mind, our private subjectivities. How can it imperialize this new space? It must need nonphysical means by which to conquer nonphysical space. Cyberspace is the perfect tool for capital here, which is why communication technologies have accelerated in complexity at such blinding speeds. Thanks to the internet, your time and intellectual labor have been more thoroughly colonized and your thoughts, dreams, and memories have been newly colonized. This the “information economy”. The internet allows you to share your thoughts and experiences and, as those thoughts and experiences circulate through cyberspace in the form of Tweets and Tik Toks, they take on a life of their own and become commodities. All commodities are, as Guy Debord describes, invested with this spectacular nature, which is to say they try to convince us they’re way more awesome and cool and interesting than they actually are. Once you actually attain, say, the Yerba Mate, it is instantly “impoverished”, losing the spectacular aura and becoming just another canned energy drink dressed up in hip, socially conscious imagery. How exactly, then, do Tik Toks and Snapchat stories operate as spectacular commodities? What are Snap stories selling? They sell you, the idea of you as a hip, indie, cool, cultured, fun-having person that goes to Tyler, the Creator concerts. They also sell the experience of a Tyler, the Creator concert, and of concerts in general. Snap stories convert your experiences into things sold to others as affirmations of your coolness and into advertisements for those experiences. Thinkers like Baudrillard argue that all of culture is like this now, and as a result there are no real experiences, or real anything, anymore. Reality has been totally subordinated to the hyperreal, to simulacra that live independently of their ostensible referents. We care more about the Snapchats than whatever the Snapchats are of/whatever they represent; we care more about making a good Tik Tok than going to the concert and having fun. As a result, Snapchats have become simulacra, or representations that don’t really represent any reality. A beautiful example of the above is in Don DeLillo’s AMAZING book White Noise. In it, the protagonist Jack and his friend Murrary drive past a billboard advertising “The Most Photographed Barn in the World”. Jack and Murray find the barn-which is just a garden variety barn-and, observing as all the tourists frantically snap pictures, Murray remarks “Nobody sees the barn.” How fucking PROFOUND is that? Just as nobody cares about the actual Tyler concert, nobody cares about the barn. The actual barn is dilapidated and boring, and the actual Tyler concert was a stressful, sweaty, smelly, painful mess and after Glitter someone threw up on you. Instead, we elevate the barn to mythic levels of importance by photographing it; as Murray elaborates, “Each photo taken contributes to the aura.” The aura of the hip music scene is similarly bolstered by Snapchats of the Tyler concert, which are beautiful and perfect and only reveal what you want them to. I’m in no way saying concerts aren’t fun; they’re incredibly fun and I miss them intensely and I was just exaggerating the barn-concert analogy. I’m also very much guilty of techno-addiction and as a result struggle greatly with “being in the moment”. Instead of using the concert as an opportunity to fashion a digital fantasy thereof, though, we should just take a couple of pictures and then be there, amongst the sweat, vomit, and everything else. At the end of the Fyre Festival documentary on Netflix, an interviewee notes that a company is charging people to sit in a luxury jet parked on a tarmac and take selfies, and that the company is successful. Baudrillard came up with all the “hyperreal simulacra” stuff in the 1970s, and DeLillo wrote White Noise in the 1980s. They fucking time-travelled. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|