|

by Saffron Sener Every Tuesday for an hour, I teach a Creative Writing course to second-graders at a nearby elementary school. Sometimes equally, I eagerly await and dread this class. Eagerness is inherent; being able to provide a creative outlet for these students as well as the general fun of planning, preparing, and actually teaching makes my experience an enjoyable one. The dread, however, stems not from the students or anything about the school or program I teach through (C.R.E.A.T.E.). Rather, it’s born from my own anxiety and apprehension to lead a group of fifteen-plus seven and eight year olds in everyone’s favorite subject: writing. I began writing creatively when I was in second grade (what a parallel!), but as I was on the younger side, I was about six then. It was something I did for fun, and it was “my” thing; I “wrote” a “book” (100+ pages of elementary-level text very heavily influenced by Sharkboy and Lavagirl) that same year. For me, writing was my path of least resistance; I struggled with math, with grammar, but stories and poems just flowed. This isn’t to say I’m perfect in my writing, or that it’s any better than anyone else’s - rather, I just found it easy and enjoyable to do. This is not universal. Leaving elementary school and entering middle and high school, when writing assignments shifted from fiction to essays and from fun to thoughtful, I began to understand the qualms. The fear of putting pen to paper. The nuances of sentence structure, the need for variance, the consideration given to avoiding word repetition. The panic at a prompt, and being told “no, no, no!” when it doesn’t quite match. The suppression of that creativity I and my peers so fortunately developed in elementary. It grew more potent in high school, when in A.P. and I.B. classes required the churning out of thousands of words every day. “Furthermore,” “for example,” “as shown by,” grew almost as reflexive as including my name at the top, followed by the teacher, class, and date (ah, M.L.A., how I don’t miss you so). Writing words became excruciating at times, especially during timed writes. Fiction - what’s that? I penned a handful of poems/stories in comparison to the hundreds of essays. To get to the point, though, I will address my second-graders. Hopefully, someday far in the future, they’ll stumble upon this blog post and be brought to the six-ish week class they were a part of now. Do not let the crushing weight of academia strip you of your creativity. In my time as your teacher, I have watched each and every one of you step (slowly, at times) out of your shell and each step is more rewarding than most else in my week. Writing is hard. That is a fact. You’ve told me that, when I ask you to write a haiku or about a character in your story. I know that. But in your excitement to share with the class, to take projects home to keep working, to continue having the class despite the school year coming to an end, I see a change - that difficulty is not necessarily a deterrent, anymore. Your poems, stories, songs, and everything else are manifestations of your incredible imagination and in the coming years as a student there will be times where that is threatened. School curriculums are capitalistic constructions rooted in getting the “best” product possible to create a facade of success that in turn funds the institution. The better the school averages, the more money they receive. Challenge that cycle. Be creative. Don’t let the constant wave of essays and requirements dull your drive to write creatively as well, like I did. For a long, long time, I wrote very little beyond that which was asked of me in classes. I’m only now, in my second year of college, falling back into what I love so much. Don’t get lost like I did.

1 Comment

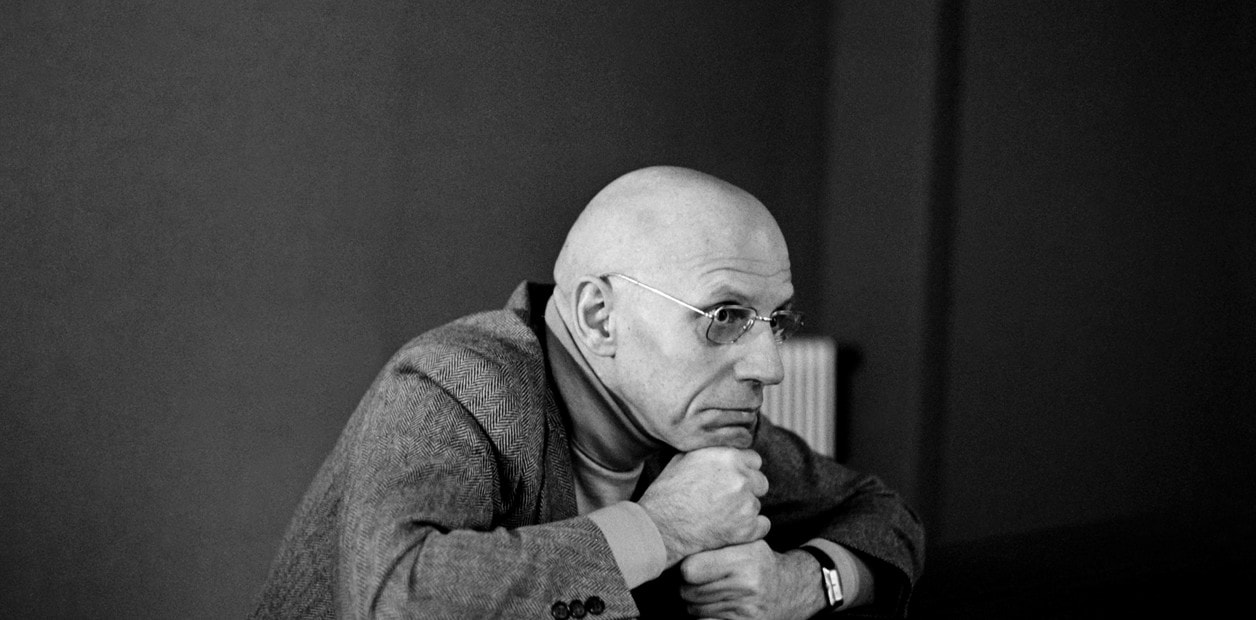

by Nash Croker What has Critical Theory ever done for us?

Alright, well, apart from denaturalising sex and gender, the Panopticon, psychoanalysis, defining race as a social construct, Hermeneutics, Semiotics, the labour theory of value and cultural hegemony...what has it ever done for us? Look, I love a Marxist-Feminist analysis of some shitty Netflix show more than the next disaffected queer. But, honestly, sometimes it feels like the most relevant any of this high-minded mumbo-jumbo will get me is a self-satisfied Twitter takedown. Beyond simply trying to understand what Butler, Althusser or Benjamin are trying to say, half of the struggle is making any of this is relevant to lived experience. I truly am glad that Berkeley’s Rhetoric department caters to this academic focus on critical theory. It really is a valuable and interesting interdisciplinary degree focus. Seriously, though, have you spoken to a Rhetoric major for more than two minutes without them name dropping Foucault, Heidegger or slagging off Freud? So much as the denigration of Arts and Humanities in favour of STEM means the small, awkwardly titled department might feel a bit misunderstood, it must be aware of its own pretentions. The modern neoliberal university may not value this field. Funding is not plenty and career prospects even worse. But the old-skool academic rigour of being plunged into purposefully dense texts - maddening until explained in class, written almost entirely by white men in the late 19th and 20th Centuries -means that, functionally, Critical Theory is an exclusionary discipline. The books are often the most expensive in the bookstore (£25 for less than a hundred pages of Guy Debord shitting on TV!?). Not only are the texts so referential of other theories and authors that you really need to have read them all to read just one, but discussions of the ideas within them are mystified in the logics of the field itself. Too often Critical Theorists appear to only be talking to each other. If ever there was an exclusive club for those with the money, time, and access to buy, read and engage in high-minded debate, then it is the school of Critical Theory. “Ok, so what? You’re deriding the theory bro now. Haha, where’s his praxis?” As, my allusion to that famous Monty Python skit suggests, Critical Theory is actually pretty relevant. The problematisation of social movements is vital if we are to see change that does not leave people behind (see applications of Intersectionality in modern racial politics). But as a discipline it needs to be more open to those without this gentil sensibility and security. Rather than working on fine-tuning debates between German philosophers, can we work to make Theories accessible to those without a costly Masters Degree? The elitism of the discipline is no wonder the Berkeley Left often feels stuck in a daydream of the 1960s. Barthes and Derrida are never going to save us. Making this important work accessible and acted upon in our justice movements may well, though. To do so may mean a few bearded Marxists get off their high horses and stop arguing with each other over posh dinners. If the Frankfurt School was so successful in deconstructing the ideology of the culture of capitalism, then why has this politics been allowed to develop its own kind of privileged, apathetic, political culture? Too many men on the Left are afflicted with cultural nostalgia for the radicalism of the ‘60s. Yet to ensconce yourself in the kind of political culture is to lust for possibilities that do not exist anymore. It is to fall foul of the kind of individualism that failed the New Left. Neoliberalism, gentrification and police militarisation mean 1968’s ‘Year of Revolution’ really only spelt the end of Social Democracy. The Civil Rights Movement won its successes (albeit limited) in white northerners willing to die in Southern violence, not through Dylan songs. Copiously reading through the political philosophy of that age, scouring Spotify for these protest songs is to individualise a political culture that is irrelevant today, if not a grave failure. The University and the world has changed. So too must the Left’s political and academic culture. by Katherine Schloss Fresh off of a Cal Day full of blue, gold, go bears, and such, my friends and I sauntered to the Memorial Glade in search of respite from the sea of frat noise we’d engaged in, expecting to wade through waves of eager prospective students. Instead, we (thankfully) stumbled upon the concert that SUPERB was putting on. The vibe we encountered on the famous sturdy patch of patchy grass was reminiscent of how I imagine it must have been when the hippies roamed Berkeley in the days of free love and peace. Truly, where have all the hippies gone?!

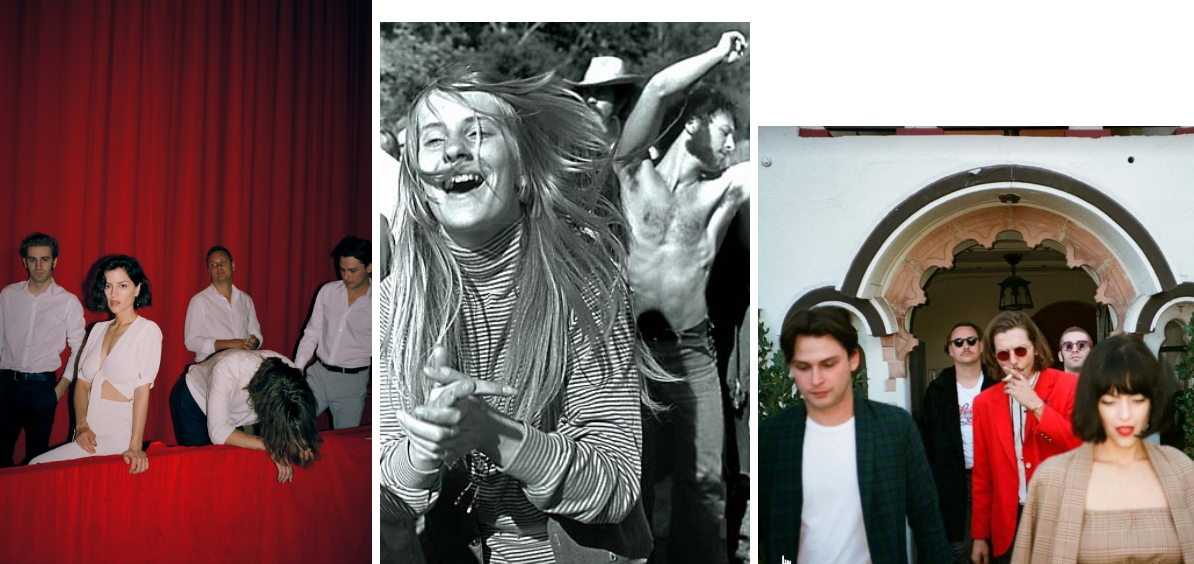

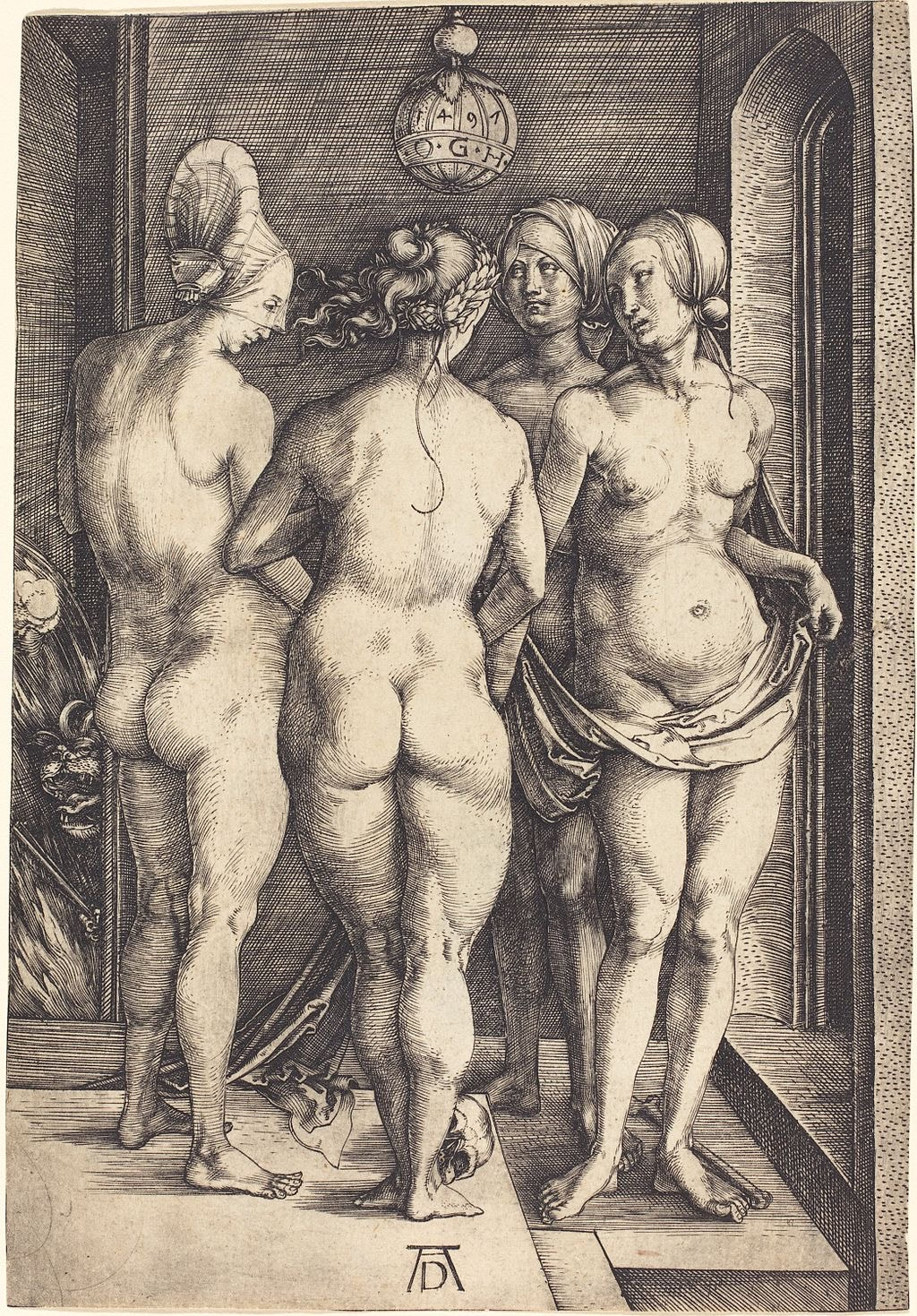

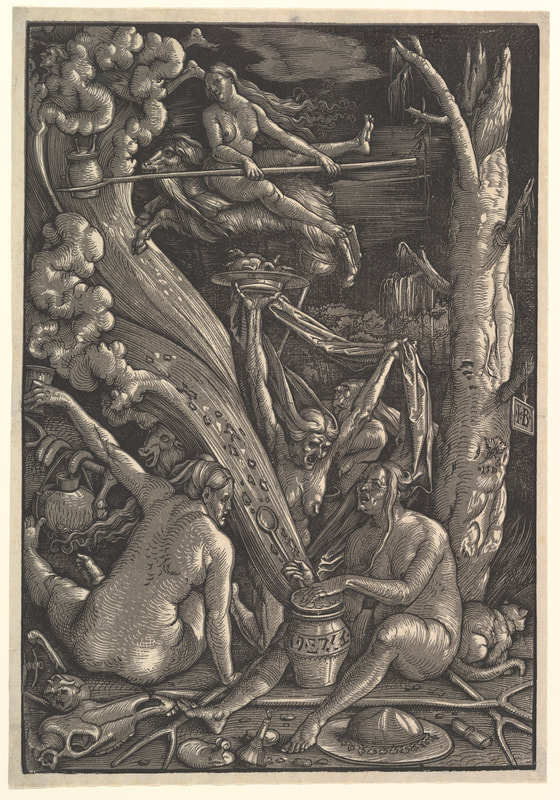

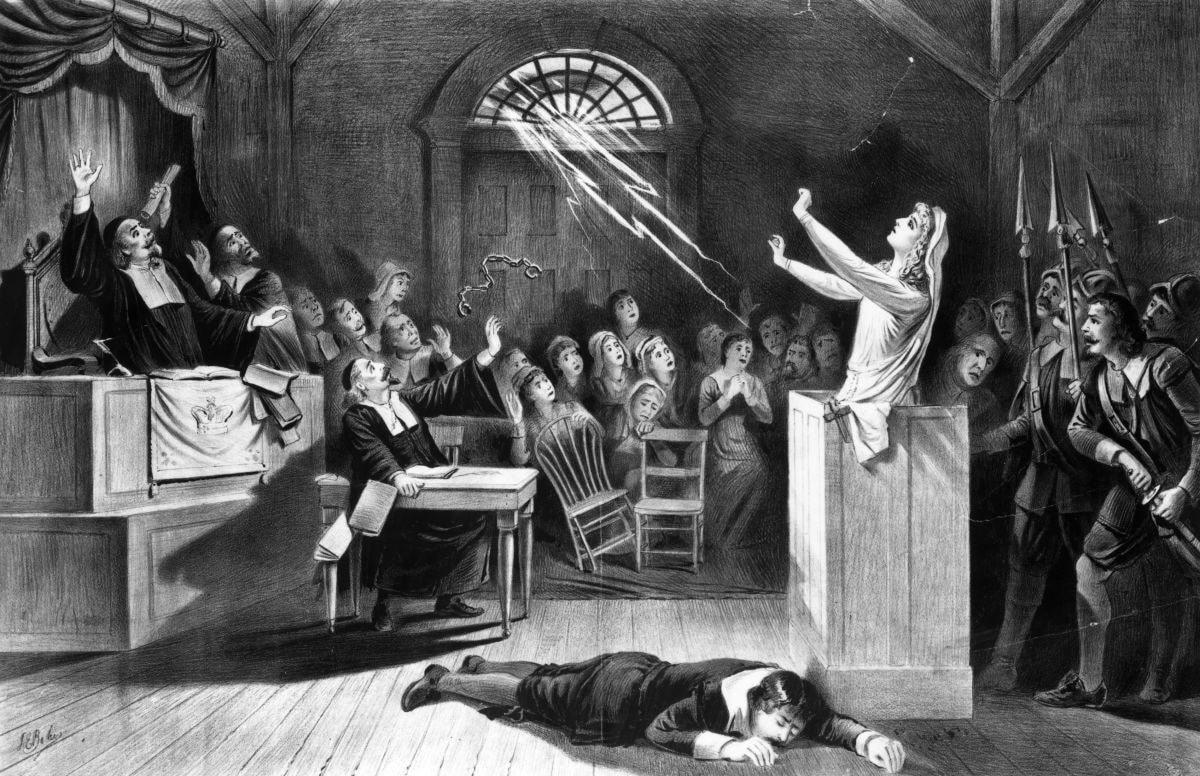

Writing this has reminded me of my obsession with Lindsay Weir and Kim Kelly of Freaks and Geeks and my envy for their ability to journey off in a VW bus to follow the Grateful Dead. I feel like music today is an escape, whereas it was once a religion. This year I’ve been unintentionally going on a sort of concert pilgrimage. The journey hasn’t taken me far physically, but it has emotionally and intellectually stimulated and changed me. I got my first true taste of the electric experience that is concert-going this past year-- my first year of college. Prior to my time here, I’d only been to a Taylor Swift concert and Vanessa Hudgens’ attempt at one in a small county fair in Pennsylvania. Coming from Orange County, I should have been exposed to more of the small groups that come out of Los Angeles, but I wasn’t savvy enough, always hyper-aware that all of my favorite songs revolved around a 70’s witchy Stevie Nicks period or an 80’s Toto howling “Africa.” But now, I have discovered my intense love for concerts. When I lived in Foothill, notes from the Greek Theater would waft over to my dorm, scoring my study sessions (or lack thereof) and making me feel as though I had started to find a soundtrack for my ever-changing life. I often heard the musicians warming up early in the day, and it felt as if we had gone through space and time together once it was all put together at night. One poignant memory of that time period was when, walking home from VLSB really late one night, I heard the last chorus of Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” a few days before he died. From Berkeley alum Jack Symes to quirky Father John Misty to all of the band nights at Thorsen house, each concert I have attended has been a unique experience that has shifted my perception of the world and of music itself. The concerts with SUPERB have been especially meaningful to me, as they transform various spots on campus that I walk past every day into sites for my infatuations with new artists. The Stelth Ulvang concert in particular was a magical event for me. Rushing from my SwingCal practice, I walked into the beautiful, moody place that is Bowles and immediately was so relieved to shake off the weight from my stressful week and to just vibe to new music with my friends. I felt connected to strangers as we swayed under the purple lights to Stelth’s soothing voice. For the most part, my concert experience this semester has been like riding a calm comforting wave, save one night where I found myself in the middle of a mosh pit. I’ve learnt to give into the flow of the music without losing my sense of self under the sparkly disco ball and amidst the crowds. I saw Summer Salt at the Corner Stone and I don’t think I stopped smiling once. At the TV Girl concert, I literally went through my whole dance repertoire (trying to avoid the fact that I didn’t know the words and just giving into it all). I was able to just simply vibe with the chill tunes… and that was exactly how I felt on Saturday. The Marías!!! What an insanely hot group they are! I’ll admit that I’d literally only listened to whatever songs my free version of Spotify had fed me-- sorry, I know that’s such chaotic energy but my laziness and lax attitude about some things culminates in having to patiently wait through three of the same ad every hour-- and yet I had definitely loved what snippets I’d heard of her smoky voice. I was not at all prepared for the presence María had onstage- my friend iconically described her voice as “sex embodied” with her black high-waisted dickies, a skin-tight cheetah top and black shades. All of that, combined with her envy-inducing blunt bangs and subtle body rolls, culminated in the creation of one mesmerizing lady. Her movements were sensuous and just self -aware enough to make me immediately want to be so beautifully intentional yet so chill. In a Noisey article, the group’s drummer Josh Conway grapples with the fact that the Marías have been described as “vintage.” I’m personally finding that there’s a timeless collective spontaneity that’s forming in many of the groups I’ve seen this year. By this I mean that the Marías have hit a sweet spot in the combination of their passions somewhere in the mix of old-timey and contemporary, in dreamy tunes that simultaneously evoke hotel lobbies with velour-covered couches and the farthest reaches of the Milky Way. I feel this is best captured by their Ones to Watch article, which says that the music makes one feel, “...transported, taken over by a sultry tranquility as you drift into a timeless space.” They’re all very put-together, care a lot about their music, and each member has a unique look, so their creative juices marinate nicely. This is especially impressive considering the group was a lovechild that sprang from the real love between the band’s eponymous lead woman and its drummer (for once the drummer doesn’t fade into the background). The music videos are a very smooth meshing of retro looks with an effortlessly cool sway set to their sexy and swanky tunes. I could-- and do-- watch “Over the Moon” on repeat, with its intermix of celestial claymation and María in her dazzling, pearly gown surrounded by her monochromatic, white-suited boys. It allows her to be central and showcases her, but not obnoxiously so. She is sexualized, but not exploitatively. Instead, she owns the milky, sparkly dream-like sequence, and its in three minutes and three seconds steals my heart and epitomizes for me what my concert-going journey has been: a time to both find my love for old-school music newly implanted in the present and to also allow myself to grow into my own body. To become my own María, enwreathed by an ivy of the songs that I now carry with me-- whether I know the words or not-- dickies above the ankle and my head held high. by Saffron Sener  Joseph E. Baker’s 1892 lithograph, Witch No. 1 Joseph E. Baker’s 1892 lithograph, Witch No. 1 Joseph E. Baker’s 1892 lithograph, 'Witch No. 1'I’ve always loved witches. This isn’t to say I was that girl in high school who “practiced Wicca” and had a pet rat or tarantula or something of the like. But, I’m (too) well-versed on the Salem Witch Trials. I did have a major Edgar Allan Poe phase from middle school until the end of high school (only a bit drawn out). It’s almost certain I’ve seen more horror movies than you - which, I assure you, is not a brag; I’ve suffered through some truly terrible films to earn that title. Any open-ended paper I can write for one of my many history classes is, most surely, about witches. Maybe it’s that I see a bit of myself in the concept of a witch. Unadulterated rage (of a womyn), rejection of men for a life of seances and spells in the woods, a certain separation from society and lingering in the dark. I’m not ascribing myself to the trope of disgusting woman as witch seen in films like the Blair Witch Project (1999) - only described, never seen - or The Wizard of Oz (1939). Nor am I ascribing myself to the seductive femme fatale witches of films such as Suspiria (2018/1977). In terms of personhood, I am not opposed to a disgusting woman or femme fatale (though these representations are clear manifestations of male anxiety to the idea of a female who rejects men). But, I would rather align myself with the women executed throughout human history for allegedly practicing witchcraft - outcasts of society persecuted for the anxieties projected upon them. I find their stories far more interesting than Wicked (the musical). I find their stories, and the fears cast upon them, more interesting than the boiled down versions of witchiness we get in Hereditary (2018) and Into the Woods (the musical). I’m not even going to touch Harry Potter. But I’m not here to embark on a survey of witchcraft. Rather, I am here to discuss something that truly enrages me; the constant representation of female nude bodies as functions of horror in horror films. I’ve hinged this on witches because the most common representation of women in this genre is as witch, in my opinion (rivaled only by the Final Girl). Look to Hereditary (2018). Or Suspiria (2018). Or The Witch (2015). What is the common denominator of the witches represented here? Their nudity. Not only are these women posed as the villians of the story in their status as “evil” witches, but this is highlighted by their naked bodies. This reliance by horror filmmakers on the female body as an inherently scary thing is abhorrent. Why must each witch movie, like the three above, end in an orgy-like gathering of naked women, dirty and writhing in orgasmic pleasure? pain? Why is the climax of fear, the supposed most scary moment of the movie, depending on the audience’s supposed disgust for the female form (a disgust most definitely reinforced by cinematic moments such as these)? And why do these scenes always seem so similar to propaganda spread since ancient civilization as a way to stir up popular fear towards groups who dissent from the common authority? When I learned about the Bacchanalia of ancient Rome, and the efforts put in by senators to end these non-approved religious festivals, it all clicked. Livy, the ancient Roman historian, writes a scathing account of these events, noting in his History of Rome: “This pestilential evil penetrated from Etruria to Rome like a contagious disease...one way of corrupting...morals was through the Bacchanalia.” In their legislation against the Bacchanalia, Roman senators emphasized their perverse (and made up) sexual nature, their essential nudeness (again, made up), and their being a threat to the sanctity of the Roman pality (really, they were more a result of existing instability rather than a cause). They dehumanized the body, describing sexual relations with animals and luxuriant, gluttonous feasts to accompany. This propaganda, most certainly unsubstantiated and untrue, sparked the usage of the nude (female, as women played an integral role in apparently attracting participants of the Bacchanalia) body as a function of fear. This continues into the Middle Ages and beyond. Works like Albrecht Dürer’s 1497 engraving The Four Witches and Hans Baldung Grien’s 1510 woodcut The Witches are two of many examples; here, again, the women are depicted as naked, outside their norm and thus scary. European perceptions of the female body required its covering to be pure, chaste, and in its “proper” state - a woman’s body in the nude was equal to a complete corruption of the self. Clothing meant civility. Katherine Brown, in her novel, Foul Bodies: Cleanliness in Early America, writes: “nudity...evoked the base, animal nature of corrupt humanity and located spiritual uncleanness in a foul body” (page 15) which was highlighted by the “fundamental uncleanness of women” (page 16) and the equation of “female genitalia...with sexual sin” (page 36). She further notes that when European colonizers encountered Indigenous groups, they were “predisposed to believe that...nudity [was] a sign of both innocence and savagery” (page 44). Thus, it becomes clear that the function of one’s naked body in a public space is that of degradation and shame - a tool for white men to further establish their power over women and people of color. 'The Four Witches', Albrecht Dürer, 1497, engraving and 'The Witches', Hans Baldung Grien, 1510, woodcut. Witch-hunts, which plagued the European continent from the 15th to 19th centuries, were the bastard of the Reformation, initiated by religious inquisitors as an inversion of religion. Witches thus became evil incarnate, and over generations large-scale, authority-driven calls for the execution of witches was adopted by the masses. They grew to represent male paranoia about the female body and her rejection of him, as the process of becoming a witch developed around the narrative of coitus with the Devil and regular (nude) witches sabbaths. Witchcraft was given to us by the elite, by the government, by officials, and reworked to become a function of the masses. A fear that we all hold - a fear that reinforces patriarchal ideologies of womanhood and the corporeal body. A fear that serves those who are on top - (rich, learned, elite, ruling) white men - in controlling those below.

And today, it has culminated into a cheap fear tactic of horror filmmakers to invoke this centuries-long development of hatred for the female form, for fear of it. Because, obviously, a group of naked women can mean only two things: the object of the male gaze and a function of their pleasure OR a rejection of their gaze and thus a realization of their fear. So, a note to anyone making a horror film - posing the nakedness of witches as their most noticeable and disgusting and horrific aspect is over. We don’t do that anymore. It’s tired, it’s lazy, it’s male, and it’s time to find something actually scary. Am I asking for the deletion of witches from modern mainstream media? No. I am asking for care, and consideration of the role; a witch in a movie now is not just a witch. She is the culmination of centuries of pain and burden and murder women have endured for witchcraft, the demonization of their bodies in the name of fear, and the creation of an identity in reaction to male anxiety of rejection. She is a victim - of (figurative and literal) violence upon her body by fearful men - yet she is a strong female role model. Appreciate her. by Akshata Atre (tw: mention of self harm)

“Sorry.” “Excuse me, sorry.” “Sorry!” “Oh my god, sorry” Ask any woman how many times a day she says sorry, and the number is probably higher than you think. Much higher. We apologize constantly. And if you’re a woman and you say “sorry” fewer than five times a day, I genuinely commend you for breaking the cycle. Because it runs deeper than we may think. I found myself confronting this reality in a less-than-frivolous sense whilst watching the 2016 teen movie The Edge of Seventeen, starring Hailee Steinfeld. Watching that movie made me so frustrated and anxious that my hands quite literally shook. And look, I know I’m in the minority here (as it’s rated 77% on Rotten Tomatoes and was positively reviewed by critics). However, as someone who has dealt with her fair share of being alone in the aftermath of difficult social situations, this movie made my blood boil. The film opens with the main character, Nadine, storming into her teacher’s classroom with the declaration that she is going to kill herself. From there, the film works backwards to uncover what has happened to Nadine up to this point, primarily the fact that her childhood best friend Krista (read: her only friend), has started dating Nadine’s uber-popular older brother, Darian. Nadine is understandably extremely upset, and being left in a fragile emotional state after fighting with Krista leads her to do some rather shockingly regrettable things, namely sending a very graphic sext to her crush and stealing her mom’s car. You can probably guess where the movie is going. Nadine confronts her brother, only to learn that her brother has problems too, like having to “deal” with their emotional mother (who does not get along with Nadine at all) and the fact that Krista is the only girl right for him (a boy who, you might remember, a super popular jock). So Nadine must apologize to him for not understanding that he has issues too and blah blah blah. She then becomes friends with Krista again, even though Krista fully ditched Nadine to hang out with Darian’s “cooler” friends. Oh, and Nadine ends up with the cute nerdy boy, because that’s what happens in all teen rom coms I guess. She even apologises to her new boyfriend because she didn’t realize that he was into her, which is somehow her fault? Look, it’s fine that Nadine apologizes and owns up to her mistakes. Like I guess ethically that’s the right thing to do. But the thing is, no one ever really, truly apologizes to Nadine. Her mother, Krista, and Darian all blame her for her emotional response to the situation without acknowledging that they have left her totally alone to deal with all of her issues. She literally has no one to talk to. She’s all alone. And yet she’s supposed to bear the burden of apologizing and begging for her forgiveness when she was just reacting to what other people have done. Why is she supposed to be okay with her brother tearing her only friend away from her? Like, what sense of male entitlement is that on his part? And seriously, are we supposed to believe that her getting a boyfriend is what makes it all better? I mean really. This is 2016, not 2006. To me, all this apologizing that Nadine must do underscores that fact that women in film and television are still, for the most part, not allowed to make mistakes. If they mess up, they have to repent right away, or else they won’t be able to move on with their lives or pursue a romantic relationship, which is still, frustratingly, the end goal for so many of these stories. However, while 2016 brought us tired teen movie tropes in The Edge of Seventeen, 2018 brought us some refreshing female representation in Derry Girls, masterfully written by Lisa McGee. This television program brought to the US via Netflix from Channel 4 in Ireland is an absolute gem of comedy gold. The show is set in Derry, Northern Ireland during The Troubles (the conflict between the Loyalists and Irish nationalists) of the 1990s. The story follows Erin, Clare, Michelle, and Orla-- all of whom are fully developed characters with vibrant, colorful, and hilarious personalities-- as well as Michelle’s British cousin James, a sweet and scared comedic punching bag you can’t help but root for. In the very first episode, we see the five teens end up in detention after threatening some younger girls on the bus. During detention, a sequence of absolutely absurd and hilarious events occurs (which I simply cannot do justice in this post). To poorly summarize: Erin tries to escape to see her crush David’s gig, Michelle tries to steal her lipstick back from a (seemingly) sleeping nun, Clare inhales a sandwich (having completed a four hour fast to raise money for children in Africa), and James pisses in a trash can (as there are no boy’s toilets at the girls’ all-girl Catholic school). When they realize that the nun is, in fact, dead, they are found out by the delightfully sarcastic headmistress Sister Michael, who proceeds to call their parents and tell them off as best she can, a difficult task given that she cares very little about her job. The episode then ends perfectly, and you are immediately left wanting more. And you get more, because in every episode the gang manages to get themselves into some kind of deliciously ridiculous mishap (which I won’t even try to summarize because you just have to see it for yourself). The point is that these multi-dimensional, strong female characters (and James) are allowed to mess up over and over again, and they are rarely made to apologize for what they’ve done. It’s understood that they’re kids, and they should be allowed to make mistakes, have fun, and be themselves. While there are cliche romantic side plots sprinkled into the show, they are never the focus, and they are never the end goal. The focus is solely on the girls (and James, kind of)-- their insecurities, flaws, and, to some extent their strengths. In Derry Girls, we finally get to see female characters as real girls with real personalities. They aren’t perfect, and they don’t try to redeem themselves all the time, because, let’s be honest, none of us really ever do that. Even Sister Michael is flawed, and through her perfect one-liners she flips the script on the common characterization of a nun. In fact, every female character on this show is perfectly imperfect, both lovable and laughable. So, to all the writers out there: stop making women apologize. We’ve apologized enough, especially within the confines of your cheesy, heteronormative romance plots. As Derry Girls shows us, stories in which women are allowed to mess up are just better. So it’s time to let women to be flawed, be themselves, and be absolutely ridiculous. It’s time to let girls be girls. by Jack Wareham Looking at the mainstream American releases of the last two decades, it’s easy to see why Susan Sontag claimed cinema was in an “ignominious, irreversible decline.” Members of the film-is-dying-camp usually point out that the films currently in theaters can’t even remotely compare to that legendary period of the early 1970s, when viewers got to see The Godfather, Badlands, Mean Streets, A Clockwork Orange, and McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

According to their commonly accepted narrative, American film’s golden age was the 1940s and 50s, when the studio system produced genre masterpieces like Sunset Boulevard and The Searchers. In the 60s and 70s some subversive, visionary auteurs flourished on a mainstream scale, including Kubrick, Scorsese, and Coppola. The 1975 release of Jaws signaled a shift toward blockbuster cinema, and Star Wars was the last nail in the coffin — American art cinema was gone, forever replaced by special effects and superheroes. Although some version of this story has been promulgated by a range of critics, it relies on some strange assumptions. First, we have no reason to believe that a masterpiece will be recognized as such right out of the gate. Most of the best American films (Citizen Kane, Vertigo, 2001) take many years to become part of the essential canon. Second, those who claim cinema is dead will have a difficult time offering an explanation for this demise. Studios have become less interested in experimentation, but film equipment has become affordable and widespread, giving a new generation of filmmakers plenty of tools to produce innovative work. Instead of dismissing an entire art form, a more productive approach would be to take Jean-Luc Godard’s advice: “Failure is much more interesting than success because it is like a sick body. You can look at it and examine it and then say what’s going wrong or not.” Two critically-acclaimed releases from March of last year offer clues as to where American auteurs have gone wrong, and diagnoses of their failures can help pave the way for future successes. On the one hand, there’s Andrew Haigh’s Lean on Pete, a film about a boy’s journey through the Pacific Northwest with a horse. Although the film left me teary-eyed, his constant “homages” to minimalist auteurs (dialogue from Cassavetes, low-angle shots through hallways from Ozu, and plot devices from Bresson) had me wondering whether Haigh had an artistic vision of his own, or was merely content lifting stylistic techniques from other directors. By the end of Lean on Pete, one might feel moved, but still long for the grungy, low-low budget days when indie directors like Jarmusch and Lynch made films with stylistic rigor and surreal inventiveness — films that disturbed you instead of lulling you into a humanist stupor. This, of course, isn’t just Haigh’s problem. Most of the indies of the 2010s seem satisfied to remain slick, efficient empathy machines: consummate entertainment, but repeat viewings yield little to nothing. Then there’s Wes Anderson, who clearly does have a unique vision. There are debts, primarily to Truffaut’s whimsy and Kubrick’s exquisite composition, but their reformulation creates a style that is, to say the least, original. And yet, Anderson’s trademark techniques (symmetrical shots, pastel colors, dollhouse mise en scène, stop-motion animation, wooden acting, and heavy irony) are devoid of substance — gussied-up kitsch. According to Anderson’s worshippers, artiness equals art, and his mere differentiation from normal big-budget high-concept blockbusters is a sign of quality. In Isle of Dogs, he elevated his vision to the realm of political commentary, and the result was embarrassing failure: a grab bag of hokey visual gags and tasteless comparisons between dogs and refugees. I heard chuckles in the audience when the authoritarian government set up a concentration camp for the dogs, as if the Holocaust was just one big puppet show, subject to hip in-jokes like everything else. These are just two films, but the problems they present — feel-good tranquilizers on the one hand, and empty artistic vision on the other — are not isolated. In the first camp, one also finds Call Me by Your Name and The Shape of Water, while the second contains Ex Machina, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. And yet, last April I saw a film that elegantly skirted both of these pitfalls: Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, which follows a clergyman’s spiritual crisis and political radicalization as he becomes more aware of climate change. Schrader’s film is intensely formalist, but for the sole purpose of enhancing its content (unlike Anderson, whose films are style over substance par excellence). And, instead of jerking tears, First Reformed embraces the genuine ambiguity of violence and refuses to end on a heart-warming note. As in Lean on Pete, there are explicit comparisons to Bresson (both in religious theme and stylistic minimalism), but Schrader is not interested in merely referencing the old masters. By placing a pared-down aesthetic in conversation with environmentalist content, Schrader accomplishes something genuinely original and substantive — a disturbing meditation on spirituality in the wake of human extinction. Assessing whether Sontag was right about cinema’s decline is a difficult task. Although those who defend her claim will find ample evidence in what’s currently playing at the theaters, cinema’s current failures shouldn’t be viewed as proof of American film’s demise. Rather, they can be used as clues: ways to critique, modify, and ultimately improve the state of film. Only through this optimistic approach could we discover new works that can rejuvenate our hope for the lost art of cinema. by Nash Croker Well, not exactly...

As a British Indian it is not surprising that I love the BBC sketch comedy show ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ (1998-2001). What is surprising is that I have only just started binging it. This Blair-era show created by and starring Sanjeev Bhaskar and Meera Syal, set a new standard for subversive comedy, turning racist caricatures on their head to tell a much needed tale about British life. I have normally thought of comedy as fundamentally cathartic. The compulsion to laugh at an observational joke serving as means to dissipate one’s anger and frustration. Sure, it cheers us up, but politically it is never going to change the world. Too often even political satire offers a politically harmless outlet for our very real world frustrations. The revolution won’t happen on SNL. If you are looking to make a political point through comedy, then getting a laugh needs to be your ambition. It is in this way that comedy can be a highly effective means of changing political culture, even if it fails to create any direct political change. ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ and its ability to get us to laugh at what its sketches are saying is precisely how it enacts its cultural political intervention. That of representing British Indians as a constitutive part of British society. What the sketch comedy of ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ performs is a sort of ‘brownface’. These second-generation immigrant comedians put on the racial stereotypes applied to their parents. Contextually this is no surprise. As the largest minority in Britain, many Indians migrated to the metropole during colonisation, most significantly, following Britain's post-WWII drive for immigrant labour from the Commonwealth. A generation later, Tony Blair’s New Labour government came to power in 1997 riding a wave of multicultural optimism based on a boom period for the economy’s financial sector. For a brief period, people of color didn’t have to blamed for the nation’s economic stagnation. And for the first real time on public television, people of colour could have their own comedy show, even if it was still limited to making jokes about being brown. Recurring sketches include the Coopers and the Robinsons - two British Indian couples competing to see who can appear most Anglicised, the superhero ‘Bhangraman’ or the pair of competitive Indian mothers. All of these sketches play on the integration of British Indians into British society. Fronting commonly recognised Indian stereotypes to highlight their inaccuracies by poking fun at their implications. ‘Bhangra man’s’ arch-enemy is the ‘Morris Dancer’, invoking a clash of civilisations so ludicrous so as to ridicule any fear of cultural invasion. My favourite sketch is the “Everything comes from India” man. Here, an excited college age son tries to tell his father about the British history and culture he is learning, only for his father to nonchalantly retort that of course his son is enthralled, because “it’s Indian!”. These seemingly laughable assertions attest to first generation immigrants fear of their children losing their own cultural heritage. The father’s reasoning is based on racial stereotypes - Jesus is Indian because he worked for his dad and managed to feed 5,000 people with a small amount of food. Yet beyond just pointing out stereotypes and attesting to generational differences in immigrant households, by defining traditional British cultures as Indian the sketch acts to educate on Indian cultural influence in seemingly accidental truths (many English words come from Indian languages). The best of these is when the son takes his dad to a Renaissance art gallery. Da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ is actually a portrait of Mina Losa, a Gujarati washer-woman by a painter in Faridabad. It’s obviously ridiculous, but it’s not a cheap joke. When the son describes her expression as “asking us whether we are observers or voyeurs” the father rubishes his claims, “she’s asking how much does this painter change because my brother can get cheap paint”. Implicit here is a Marxist critique of Western art criticism itself, amplifying the economic relations inherent in the production of artworks. Up next is Da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’. Indian, of course, because it depicts twelve men sat around a table for dinner - “where are the women?”. On one level it is playing up to Britain's moralising perspective of Indian society as more patriarchal and thus unenlightened. And yet, here is a principle artifact of the cultural precedent for the Enlightenment ironically being shown to be just as patriarchal and seemingly primitive. The son then moves through as many big names of European art that he can muster - Donatello, Rafael, Tischen, Picasso, Lowry, Reuben, Botticelli, Michelangelo. His father’s silly claims to Indian-ness are once again only half the story. Here the show is highlighting how Eurocentric the canon itself is as well as the developments of artistic form made by and presented in Indian art. The sketch concludes with “the representation of the physical male perfection”; Michelangelo’s ‘Statue of David’. Crucially, however, according to the father, it’s not Indian. Why? Because of David’s small penis. The colonised subaltern was seen as emasculated by the imperial white man. Here, however, white Western masculinity is emasculated by its highest art. It is a slight break from the racial stereotypes of the sketch, but this little truth serves to ridicule the caricatures themselves. It is then how this comedy can evoke laughs from racists and British Indians alike that makes it so effective. On one level it seems as if brown people are making fun of their own otherness, yet on another British society’s racist attitudes are ridiculed by employing the ‘brownface’ mask of racial stereotypes. It is in this subversion of the racial caricature that ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ managed to make some of the most pointed critiques of British society. All while representing British Indians in a public broadcast comedy show. For one like myself, it is the show’s ability to highlight just how Indian Britain really is, reclaiming British identity, that makes it unequivocally some the nation’s greatest ever culture. by Ryan Simpkins I want to get a tattoo of this very large very ugly bug. This massive, enraged, monster who was forged in the midst of a Toxic Jungle devouring the Earth and human civilization clinging to it. This creature, this rolly polly looking mother fucker, is an Ohmu. An ugly, angry, defensive thing. These guys are the stars of Hayo Miyazaki’s Nausicaa and the Valley of the Wind, a film about a young woman (the titular role) who sees the beauty in the bugs’ worn husks and the truth of their nature. She’s been my hero since I was like 10, and that’s because her movie fucking rocks. Set in the distant future, the human race is barely surviving, kingdoms hostile and desperate for resources as the Toxic Jungle spreads its spores across the face of the earth. Only one small village hidden in a valley remains strong, led by a princess who seeks to understand the natural forces that works to kill them.

Miyazaki’s name commonly evokes childhood memories of cute cartoons about massive flying forest spirits or terrifying ones of parents being turned to pigs. Nausicaa may have been the first Miyazaki film I was exposed to and has remained my favorite since that day in 5th grade where the kids were separated by assigned gender, one half getting told about puberty and the other watching these bugs rule the earth. I rewatched this movie for the I-don’t-know-how-manyth time the other day and became actually literally emotional over how much I loved it. The color pallet changes depending on the location: deep hues of blue and purple filling the scenes of the Toxic Jungle juxtaposed with the lighters greens and yellows of the struggling human civilization. The score reminds us we’re in a dystopian sci-fi with synth tunes coming from an 8 bit video game, familiarly found in the Tron / Blade Runner that the 1980s expected for us. This too is leveled out with a more simple score, music constructed around a simple “la la la” coming from a little girl's voice, reminding us of the youth of our hero as well as the rudimentary levels the Wind Valley’s civilization has come to due to civilization’s collapse. I could watch the first 30 minutes alone on repeat, constructing the beauty of the jungle that could kill Nausicaa in seconds. Her small village protected from the Jungle’s air by the ocean winds and mountain walls, a village filled with people who love and admire a princess who saves men by soaring on her glider and communicating with animals through music. Life is good in these moments, even when an enraged Ohmu hunts one of our protagonists, eyes blind with red rage, or when a massive airship crashes to the valley floor, another princess of a distant land dying in Nausicaa’s arms. These moments of excitement pale in comparison to the devastating antagonism that is to come, making the Valley’s early moments in the film quaint. Nausicaa deals with all the classic Miyazaki films as bluntly as ever. The film’s clear environmental message comes from the humans’ desperation to fight against the Earth’s forces while Nausicaa works to understand them, recognizing that it is not the end of the world but the end of the human race as is, one that needs to adapt and work with the Jungle and its defensive insects. Miyazaki’s infatuation with flight is present as the Valley’s civilization and irrigation is dependent on wind, Nausicaa seldom seen without her glider. It is anti colonial in it’s genuine antagonist, mostly metal imperial princess Kushana, who comes to the Valley of the Wind to retrieve lost cargo from the crashed airship. Kushana takes the Valley, one of the last homes of the human race as her own, and forces the Valley people to live under her rule and house her war machine. Nausicaa's characterization is inextricably feminist, working to balance conflicting archetypes of “masculinity” and “femininity” to balance into a stable person, a true leader. She moves between being nurturing thinker and pacifist to a violent and determined leader. She suppresses both sides, hiding her love and study of the Jungle’s toxic plants as well as shaming herself when she becomes too emotional. Nausicaa's outfits change color depending on this, moving from calm blue to heated red (mimicking the colors of the eyes of the Ohmu transitioning from angry red to neutral blue). She only reaches true victory in the films end where the Ohmu embrace her as she has them, her outfit holding both red and blue within it, fulfilling a prophecy set up in the film that tells the story of a man. I won’t pretend I have anything deep to say, nothing overly intellectual or inspired. I’m only writing this because I love this movie. I love the hideousness it invents, how it’s painted with such beauty and care. A nasty massive bug will be the center of a scene of serenity, gorgeous colors and sounds creating a landscape of lovely poison. In the middle is a girl, one conflicted, angry girl with the weight of the human race on her shoulders. And atop that ugly Ohmu surrounded by the toxic air, she is able to just breathe. by Katherine Schloss Lately I’ve been too caught up in it all to sit down and truly commit myself to binge watching a new show. Summer nights spent cramming One Tree Hill until my eyes watered are a far-off memory. Then, my roommate suggested Pushing Daisies, and I absentmindedly starting watching the pilot episode as I packed for spring break. Straight off the bat I was incredibly intrigued by how intentional the cinematography felt. It was very Wes Anderson-esque, with odd color palettes and quirky, witty one liners that are given care and attention. A few episodes in, I discovered that the show was tragically discontinued after two seasons. This dilemma has plagued me often in the niche, cult classics that I tend to be drawn to (another example being Freaks and Geeks). I often wonder how it is that other shows can gleefully exist with their cliff hangers, mistaken identities, etc. while my shows must forever be frozen in time, subject to the powers that exist outside of their realm of existence, a reminder that while trying to maintain my image of the characters as very real, there is also the very real fact that they are mere creations. Is it better that the end is left up to the imagination? Does this extend their existence as never-ending and incapable of being sugar coated and boxed into a set path? Should you even start a show knowing full well that there won’t be any satisfaction of a resolution at the end?

Shows like this are often overlooked by mainstream efforts to drag crime shows on with 10 plus seasons, playing out every possible scenario and stretching the characters and their stories thin. I don’t want to belittle shows that rely on the malleability of their characters in such a way, but there is something to be said about a storyline where characters are created with a certain depth and groundedness that makes you identify so heavily with them.That’s exactly why I find shows such as Pushing Daisies and Psych so refreshing. Both center around male protagonists who have tumultuous relationships with their fathers and are subject to playful yet often traumatic childhood flashbacks. However, they differ in a few pertinent ways: one leading man has a special, mystical gift and one merely pretends to. Psych therefore manages to cross a fine line as Shawn (the main character), a restless soul who cannot hold down a job for more than a few weeks at a time, finds his calling by pretending to be a psychic for the Santa Barbara police force, secretly relying on his keen detective abilities that he learned through years of unwanted daily training through his father. There is an awareness and lightheartedness that comes with the knowledge that he cannot sustain the act until the end of time, making the show, with its endless references to obscure 80s-isms, entirely endearing and digestible. It is decidedly real in its location and presentation of realistic situations, and yet there is a sort of blatant and cheeky undertone of the ridiculousness of the legal system and detectives in general. In comparison, Pushing Daisies is presented through the steady voice of Jim Dale-- notable for his narration of the Harry Potter audiobooks-- relying on the fantastic element of its main character (Ned) possessing the ability to bring dead people back to life. This gift comes with two catches: firstly, if kept alive for more than a minute, someone else randomly dies; secondly, Ned cannot touch the person again without them returning to their dead state. Once he brings his childhood love back to life, there exists the heart-aching situation in which they cannot touch. This creates, within the modern fairytale of sorts, a unique ability to explore a male character’s affection for a woman minus the usually heavily-present physicality that generally comes with TV’s depictions of lust and love. His inability to touch her is, indeed, very touching. In Psych, this plays out as a fragile man’s chase of the head detective’s affections, turning the common power dynamic on its head in a cat and mouse chase that involves a strong woman’s dedication to her career. Both shows are decidedly unique despite their existence within the detective genre, each with a nuanced ability to deliver comedy and commentary with heart and flair despite their decidedly niche existences. It can be argued that these shows warp our understanding of crime and the criminal justice system. Instead of developing “mean world syndrome,” which causes viewers to perceive the world as more dangerous than reality, these particular television programs make the viewer feel as though they should go into the business of solving murders. I certainly considered criminal justice after obsessing over Sherlock in its delicious Britishness and addictive portrayal of the analytical process that accompanies solving a murder or crime. In a similar vein, the Pushing Daisies creator Bryan Fuller hoped to create an appreciation for life despite the show’s inherent focus on the topic of death. His Amelie-inspired amalgamation of patterns, vibrant color schemes, and quirky dialogue may have been cut short, but the show’s defiant spirit lives on. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|