|

by Ryan Simpkins Last night, I decided to drink and watch Police Story with my friends (Criterion Collection just had a sale). The moon was high and vibes were chaotic as we rushed into Safeway at 10:30 PM on a Monday night looking for chips and beer. First person I see is a guy who I only kind-of know, just a bit. People make me feel flustered, especially guys who I only kind-of know and tried to flirt with one time three years ago at a bad party, so I decided to get away from that potential social interaction. I dove into the chip aisle, only to see a guy I was friends with the weekend of my freshman orientation where we only bonded over smoking weed and how I was completely terrified of college. He has become one of those “going to pretend I’ve never met you before” people I see on campus and avoid for my social anxiety’s sake. And here he was. Blocking me from hiding from the other social interaction I was avoiding. In the chip aisle.

I decided to go back and talk to Jack. It went fine, convo was pleasant, and I told him about our plans to drink and watch Police Story (cause Criterion Collection just had a sale). So then Jack goes, “why is that Criterion?” And, honestly, valid question. For those of you who don’t know, Police Story is a 1985 cop-action-comedy starring, stunt choreographed, written, and directed by Jackie Chan himself. My boyfriend thinks he’s cute, my favorite director loves his work, apparently he’s politically weird but idk, I just know his animated TV show and now, I guess, Police Story. I’m not going to try to explain the plot to you, because honestly, I do not remember. Chan is a cop, he’s bodyguarding some lady, and the lady is also working for the bad guys. Something to do with a court case. Anyways. There are multiple reasons why this crazy fucking movie belongs on oh-so-sacred-and-special and film-twitter-deemed-holy Criterion Collection. To start, the film was fully conceived by one of the greatest stuntmen to have ever lived, and so the simple form of filming is brand new. His action sequences are genuinely incredible, mostly existing in few long shots with intense zooms to accentuate context, intensity, or perspective. A close-up on Chan will zoom out to reveal an entire city block of fighting men. A landscape of a bus speeding by shoots in on a minuscule Chan climbing the landscape, the now extreme close up revealing that he just missed the bus he’s been chasing down. It’s like he understood the theory that long shots are the only true artistic film form and combined it with snapchat technology. The feats themselves are so undeniably unbelievable that we would jump from our seats and yell, my boyfriend’s housemate coming down multiple times to ask us to quiet down. At one point, Chan jumps down multiple stories by sliding down a string of fairy lights, electricity exploding around him as the bulbs burst. I think he wanted to show, with his long shots and extreme zooms, that these stunts were truly practically and really him, giving credit to the stuntmen who perform them. These stunts are fun to watch not only due to the unfathomable acts performed, but because Chan really does have an aesthetic sense of style. Every set piece and character is color blocked in primaries, one chase scene consisting of one all green, one all yellow, and one all red car. A village literally collapses as Chan and the goons plow through it in their cars, bright blue buildings and huge red awnings falling into a colorful rubble. The characters themselves are bright and stylish, wearing pale yellow turtlenecks or all cyan jumpsuits with a flaming orange scarf. Police Story is a fun film to watch, your eyes entertained endlessly. That being said, there are also plenty of valid reasons to question why it was given the Criterion esteem. Chan excels in style and action, but any moment where the film tries to be anything other than action (Chan, too, trying to shake off his action star role in moments for intense drama or comedy shtick) falls awkwardly and confusingly flat. For example, there’s a scene where Chan wears a very noticeable outfit, followed by a scene where someone else is wearing the exact same outfit. But no one says anything? There are many moments where a character will cross a line with a woman (saying something offensive, physically attacking her, sexual harassment/assault, etc), and the women or characters around her will not acknowledge. There’s a scene where Chan forgets that it’s his birthday, comes home to a surprise party (where every single guest is a woman), and has cake thrown in his face by offended women multiple times. Like, three times. It’s not an action scene. Why does he have so many cakes? There’s a scene halfway through the movie where Chan, for some reason, is left to watch a whole police station alone. As the scene explores, one man manning all the station’s phones is a hard job, so Chan juggles between phone calls, accidentally referring to one caller as another or hanging up when he meant to hit hold. He eventually gives up and hangs up every phone, only to realize the confusion has left him in a web of phone lines, tangled in a comedic mess. It’s impressive that he envisioned such choreography, and the physical comedy is pretty funny. But the calls Chan ignores are literally women being raped or beaten by men. And Chan just eats his ramen. That pretty much sums up the whole of Police Story. Chan performs some flashy and well-shot stunts that leave you asking how he did it, as women suffer at the expense of a joke. At least he nailed the depiction of cops abusing their power and ignoring their duties to serve themselves. Maybe that’s why they put it on Criterion.

0 Comments

by Ryan Simpkins I want to get a tattoo of this very large very ugly bug. This massive, enraged, monster who was forged in the midst of a Toxic Jungle devouring the Earth and human civilization clinging to it. This creature, this rolly polly looking mother fucker, is an Ohmu. An ugly, angry, defensive thing. These guys are the stars of Hayo Miyazaki’s Nausicaa and the Valley of the Wind, a film about a young woman (the titular role) who sees the beauty in the bugs’ worn husks and the truth of their nature. She’s been my hero since I was like 10, and that’s because her movie fucking rocks. Set in the distant future, the human race is barely surviving, kingdoms hostile and desperate for resources as the Toxic Jungle spreads its spores across the face of the earth. Only one small village hidden in a valley remains strong, led by a princess who seeks to understand the natural forces that works to kill them.

Miyazaki’s name commonly evokes childhood memories of cute cartoons about massive flying forest spirits or terrifying ones of parents being turned to pigs. Nausicaa may have been the first Miyazaki film I was exposed to and has remained my favorite since that day in 5th grade where the kids were separated by assigned gender, one half getting told about puberty and the other watching these bugs rule the earth. I rewatched this movie for the I-don’t-know-how-manyth time the other day and became actually literally emotional over how much I loved it. The color pallet changes depending on the location: deep hues of blue and purple filling the scenes of the Toxic Jungle juxtaposed with the lighters greens and yellows of the struggling human civilization. The score reminds us we’re in a dystopian sci-fi with synth tunes coming from an 8 bit video game, familiarly found in the Tron / Blade Runner that the 1980s expected for us. This too is leveled out with a more simple score, music constructed around a simple “la la la” coming from a little girl's voice, reminding us of the youth of our hero as well as the rudimentary levels the Wind Valley’s civilization has come to due to civilization’s collapse. I could watch the first 30 minutes alone on repeat, constructing the beauty of the jungle that could kill Nausicaa in seconds. Her small village protected from the Jungle’s air by the ocean winds and mountain walls, a village filled with people who love and admire a princess who saves men by soaring on her glider and communicating with animals through music. Life is good in these moments, even when an enraged Ohmu hunts one of our protagonists, eyes blind with red rage, or when a massive airship crashes to the valley floor, another princess of a distant land dying in Nausicaa’s arms. These moments of excitement pale in comparison to the devastating antagonism that is to come, making the Valley’s early moments in the film quaint. Nausicaa deals with all the classic Miyazaki films as bluntly as ever. The film’s clear environmental message comes from the humans’ desperation to fight against the Earth’s forces while Nausicaa works to understand them, recognizing that it is not the end of the world but the end of the human race as is, one that needs to adapt and work with the Jungle and its defensive insects. Miyazaki’s infatuation with flight is present as the Valley’s civilization and irrigation is dependent on wind, Nausicaa seldom seen without her glider. It is anti colonial in it’s genuine antagonist, mostly metal imperial princess Kushana, who comes to the Valley of the Wind to retrieve lost cargo from the crashed airship. Kushana takes the Valley, one of the last homes of the human race as her own, and forces the Valley people to live under her rule and house her war machine. Nausicaa's characterization is inextricably feminist, working to balance conflicting archetypes of “masculinity” and “femininity” to balance into a stable person, a true leader. She moves between being nurturing thinker and pacifist to a violent and determined leader. She suppresses both sides, hiding her love and study of the Jungle’s toxic plants as well as shaming herself when she becomes too emotional. Nausicaa's outfits change color depending on this, moving from calm blue to heated red (mimicking the colors of the eyes of the Ohmu transitioning from angry red to neutral blue). She only reaches true victory in the films end where the Ohmu embrace her as she has them, her outfit holding both red and blue within it, fulfilling a prophecy set up in the film that tells the story of a man. I won’t pretend I have anything deep to say, nothing overly intellectual or inspired. I’m only writing this because I love this movie. I love the hideousness it invents, how it’s painted with such beauty and care. A nasty massive bug will be the center of a scene of serenity, gorgeous colors and sounds creating a landscape of lovely poison. In the middle is a girl, one conflicted, angry girl with the weight of the human race on her shoulders. And atop that ugly Ohmu surrounded by the toxic air, she is able to just breathe. by Ryan Simpkins I love lady movies. About ladies, yes, duh. But directed by ladies? Wowzers. My heart flutters.

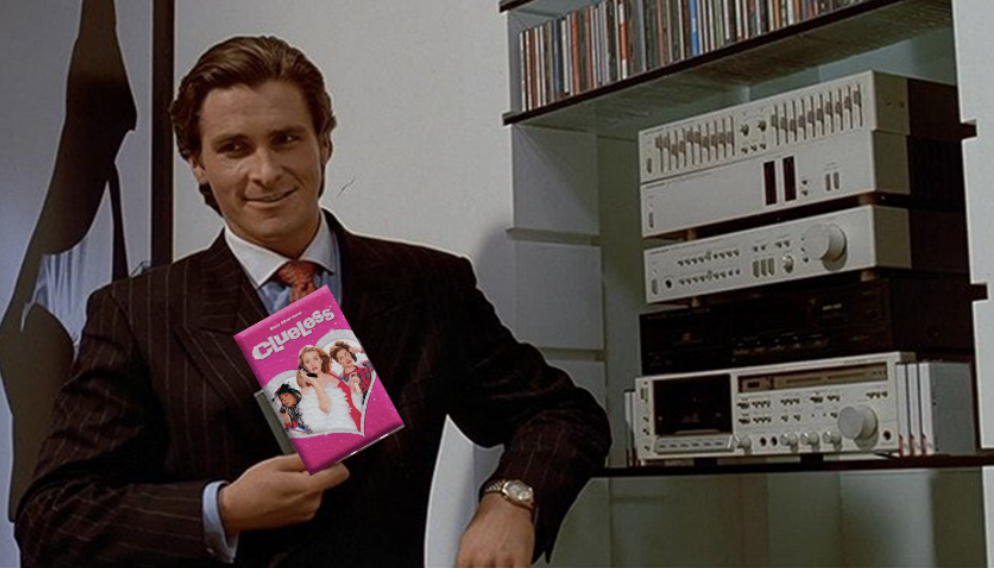

This list is critical, personal, and most certainly incomplete. Some films I intentionally omitted, due to either my lack of interest, my concern with their politics, or my not having seen them. I’m sure you will read this and find flaws, be it my selection being too western, too white, or that you’re simply not seeing your personal favorite on here. And that is 100% valid. I haven’t seen every film ever made, and while I’m working on it, I would very much love for you to express necessary considerations to add to my ever growing list of films by female directors! I am but an amalgamation of the films I’ve seen and my thoughts on them. I would love for you to help me grow. That being said, I hope you enjoy my thoughts on some of my favorites and check out at least a few. Little Women (1994) dir. Gillian Armstrong Winona Ryder is gay, and I’m in love. Zero Dark Thirty (2012) dir. Kathryn Bigelow I feel I must mention this force of nature of a film, while I cannot necessarily recommend anyone to watch it. It’s intention and themes are heavily debated. I personally see it as a film on the determination of the West to terrorize. The film stars Jessica Chastain as a government agent who does bad things that ultimately lead to a “justifiable good” (“good” defined by the state, for the state, a “good” one cannot justify as such given the context). Some biopics centered on a female lead dealing with war would sacrifice complexity for an idealized characterization. This creates a character who is perfect, "woke", a role model. This idealized role model is unfair and unjust, spreading a harmful logic on the nature of (white western) women involved in war while making a bad movie (i.e. Mary Queen of Scots). Zero Dark Thirty does not do this, but instead paints a brutal image of a brutal figure desperate to win a fight she cannot bear to handle the full implications of. (Note: I should say this was my interpretation of the film. I did not see Bigelow’s most recent film Detroit, but from what I’ve heard about the film’s confused and overtly violent content as well as it’s questionable intention coming from a white filmmaker, this makes me reconsider my initial understanding of Zero Dark Thirty.) Lost in Translation (2003) dir. Sofia Coppola Look. I’m not a big SofCop gal. Her movies are very white with themes that range from borderline to straight up racist. Plus, they’re often boring. I know that. I stand by and fight for that. That. Being. Said. Lost in Translation is one of my favorite films, quietly capturing a young woman observant and ignored. In Japan, she meets an older man who promises to see her for who she is. Two negative people fall in love because they understand their negativities as valid realities. Yes, a white romance with the backdrop of Japan serves a white girl’s feeling of overwhelming introversion, literally lost in translation. Still, I have never felt more seen by a movie as I did when I was 17 watching this one. Mustang (2015) dir. Deniz Gamze Ergüven Turkish film about sisters dealing with being sold off as child brides. Not only a well done take of a political conversation made entirely personal but aesthetically serene. Like Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation or Virgin Suicides, Ergüven uses hazey soft light and brightened natural colors to create a dreamy femininity, capturing a girlhood while the content is often somber. This is an aesthetic very popular among white women with Pinterest boards, perhaps due to Coppola’s influence. Ergüven applies this organic and feminine style taken by white women and uses it to make a film centered on Turkish politics. Little Miss Sunshine (2006) dir. Valerie Faris (and Jonathan Dayton) The invention of quirk. Lady Bird (2018) dir. Greta Gerwig Every single character featured in this film could have an entire film dedicated to them and I would watch each and every one. Leave No Trace (2018) dir. Debra Granik Easily one of the greatest films of 2018. Granik continues her legacy of discovering young female talent as Thomasin McKenzie is a joy. American Psycho (2000) dir. Mary Harron Men suck and women get that, dope. Clueless (1995) dir. Amy Heckerling Another one that’s morally complicated once you think about it, but hey, so is high school. Can You Ever Forgive Me? (2018) dir. Marielle Heller I’m a strong believer in Melissa McCarthy. She’s obviously brilliant in Bridesmaids and in her SNL cameos as Sean Spicer, but she also makes a lot of shitty movies. Most of these films are directed by men (often her husband), and they’re simply not good. That being said, McCarthy is always able to shine through, exhibiting moments of personal intimacy so bold you’ll be like “why is this woman crying in a film about Paula Deen teaming up with girl scouts who start a girl scout terf war, and why am I crying watching it?” Anyways, the bitch is brilliant and never gets a chance to show it. Heller recognized this, connected with McCarthy, and gave us one of the greatest performances of the last year (followed by Richard E. Grant’s in the same film, an underrated artist now finally getting his recognition). Wonder Woman (2017) dir. Patty Jenkins Say what you will I loved this movie and got emo watching the Amazonians. Me and You and Everyone You Know (2005) Miranda July Weird and great. The Babadook (2014) dir. Jennifer Kent I once considered this the scariest film I ever tried to watch. Great metaphors on postpartum, widowing, and being a single mother. But so so scary. Jennifer’s Body (2009) dir. Karyn Kusama This is feminist and I have proof. The Invitation (2015) dir. Karyn Kusama The hardest hitting slow burn thriller I’ve ever seen. Kusama slaps. Capernaum (2018) dir. Nadine Labaki Harsh and long, but worth the watch. Gorgeous and left alone, like Sean Baker’s fictional documentarian style. Labaki is able to pull some of the greatest performances I’ve ever seen from children. Big (1998) dir. Penny Marshall Okay okay okay, this film is obviously flawed in a lot of ways if you think about it too much (too much being at all). But it’s an absolute classic and so here it is. The Parent Trap (1998) dir. Nancy Meyers I literally do not even have to say anything you don't already know. Holiday (2006) dir. Nancy Meyers An adorable female centric romcom that will make you crush on Jack Black. I showed this to my boyfriend and he cried. Meadowlands (2015) dir. Reed Morano Olivia Wilde loses her grip on her sense of self after the loss of a child. Brutal watch. Outstanding debut by director/cinematographer Reed Morano (of Handmaid's Tale fame). Decided to DP her first project as a director. Damn. We Need To Talk About Kevin (2011) dir. Lynne Ramsay There’s honestly too much to unpack here. Postpartum depression; women deemed “hysterical”; male ego, entitlement, and violence; a gr8 cast; eerie as fuck; just watch it. Obvious Child (2014) dir. Gillian Robespierre Romcom about abortion. Fucking cute and fucking funny. This movie made me unafraid of the realities of reproductive health that once paralyzed me. Must see. Persepolis (2007) dir. Marjane Satrapi (and Vincent Paronnaud) Adapted from the autobiographical graphic novel written by Satrapi. A delightful, grounded story on punk girlhood as we watch Satrapi grow to become an independent activist with the facts of war torn Iran surrounding her. This film is badass. An Education (2009) dir. Lone Scherfig I’m a slut for female centric films about age gap romance. And Carey Mulligan. Shirkers (2018) dir. Sandi Tan Inspiring and nostolic. Teenage girls can rule the world, having the ability to make a historical dent without anything to show for it. Will make you want to see the film that never was so badly. Electrick Children (2012) dir. Rebecca Thomas Phenomenal debut by a director capturing an accurate and personal focalization of an innocent teenage girl who wants to grow. Thomas’ résumé has been filled with promising projects (Looking for Alaska, The Little Mermaid) that have locked her in pre production for years, only having directed a poignant episode of Stranger Things and a short since her feature. Free Thomas’ Career!!! The Matrix (1999) dir. Lana and Lily Wachowski This movie is fucking wild, absolutely goofy, and totally cool, opening up people’s minds to simulation theory, androgyny, and those skinny 90s fashion glasses. As you may have read on any fan forum site, the film’s character Switch was originally written to transition from female to male upon entering the real world. This plot point was ultimately cut from the script by the studio, but the actress cast and character designed were very intentionally androgynous. HONORABLE MENTION: Cam (2018) dir. Daniel Goldhaber Cam is a film about a sex worker written by a sex worker (the stellar Isa Mazzei). It’s funny, spooky, sex positive, and aware, completely tuned into its story, characters, and audience. Goldhaber is genderqueer, and I’ll do anything to recommend this super fun movie to people. by Ryan Simpkins I dunno if you’ve seen Uptown Girls, but it’s got everything: early 2000s nostalgia, sassy 9 year old Elle Fanning, peak Brittany Murphy, cute boys, teacup pigs, everything. I grew up watching this film. I idolized Elle Fanning, a young girl who knew what she wanted, who was dedicated to getting it, who wasn’t afraid of telling people off. Plus, she has really cute sunglasses. I kind of assumed this film was a staple in coming of age chick flicks, right up there alongside 13 Going On 30 and Clueless. But I recently discovered so many people that I know and love haven't even heard of this shit. Bitch, we’re changing that right now! It’s free on YouTube! I recently rewatched the film, and not only did I fully enjoy it, I recognized a theme I had never processed before that becomes key to my development as a person: Both leads struggle heavily with their own forms of mental illness, and it is explicit.

Set in early 2000s New York, Murphy plays Molly, an orphaned heiress of her father’s rock star fame and fortune (think Frances Bean but less punk and more Barbie). Dressed in glittering sequins, she's lived her entire life upon a cushion of privilege outside any realm of harsh reality. That cushion is suddenly yanked from beneath her when she discovers her fortune’s been stolen, her penthouse is foreclosed on, and the majority of her social circle begins to push her out of their lives. She is a 20 something child with no work experience. This leads her to nanny for the most impossible child: lil’ baby Fanning. Fanning plays Ray, a child with a track record of disposed nannies, an absent mother, and a father in a coma. She loves organization, hates germs, and must be in control. She has been in therapy since she was 3 and practically raised herself without any consistent guardians. So this fucked up woman child is now tasked with caring for this fucked up old soul baby. Hilarity ensues as these polar opposites discover *~they aren’t so different after all~*. But the film goes deeper than surface level character development of the “odd couple” trope. Both girls have suffered from neglect, and therefore have unexplored afflictions rooted deep in their being. These illnesses are written off by friends and family as “quirky” rather than major ailments that keep them from functioning. Through their relationship, these two young women are able to unpack lifetimes of mental illness via much needed affection, attention, and love. Molly suffers from a serious dissociative disorder. Part of this is likely to stem form her strange fairy princess reality: her parents raised her like royalty only to die and leave her alone with their riches. There's never any mention of who continued to raise her after her being orphaned at 8, though she mentions having lived in her penthouse since she was 2. She has existed in this comfortable privilege since she was young, and it seems as though no one has thought to care for the girl who seemingly had the world. So, she’s used to this surreal isolation and lack of genuine connection. When she discovers her father’s manager has fled the country, taking her entire fortune with him, Molly dissociates. Murphey’s face becomes slack, eyes glaze over. The audio fades out those around her talking reality and logistics. When she comes too and the audio snaps back, she carries a calm smile and ensures everyone that this man will return, even though she knows from previous experience that when people leave, they stay gone. She deals with tragedy via this dissociation, denying a reality she cannot come to understand. She later tells Ray of her reaction to her parents death, a scene I took as outlandish as a kid that I now find very familiar. She staggers to explain how everyone's “voices became a blur” how she “couldn’t even recognize their faces… they became blobs, and then they grew fangs.” Young Molly could not connect with the reality presented and so went into a panic, losing a grip on reality and, as we’re able to see from her outlandish behavior as an ‘adult’, never fully got it back. This is only one aspect of her emotional ailments as her mood swings lead her irrational behavior to drastic situations. Molly sways back and forth between hippie child happiness and enraged desperation. Early on, Molly meets singer-songwriter-sad-boi Neal at a party and believes it’s love at first sight. She takes him home and loves him to pieces as they spend 48 hours in the same room. When he tells her he needs to leave to “rejoin the human race,” she breaks. Moments before their breakup, Molly tells her friend on the phone she needs out, that she’s “not a love machine.” But now he ends it, and despite her statement seconds before, this sends her into a spiraling obsessive depressive episode. She sobs in a couch surrounded by take-out boxes and rotting food. She shows up to his apartment uninvited in the middle of the night. She buys him gifts worth thousands of dollars despite the fact that she is broke. He falls in and out of this relationship, taking her attention until he begins to realize her “obsessive compulsive irrational behavior”. Fast-forward, Neal’s song inspired by his romance with Molly becomes a hit, he's super successful while she’s in the midst of a mental-breakdown. Molly has an episode, running past scenes of connection she has never had (romance, fathers, etc) while Neal’s hit single blares in her mind. She runs to the center of a bridge and climbs the railing, the music cutting abruptly before she jumps to the depths below her. Yeah, Molly just tried to fucking kill herself in this chick flick about babysitting and boy bands. And yet the film flips this into a funny moment as Molly’s head never falls below the surface. The lake is more like a pond. The severity of her suicide attempt build up is done respectfully; genuine for Molly whose characterization has built up to the moment, and the sound mix having us empathize with her anxiety. But what follows is relief met with laughter. Thank god she jumped into a pond of sewage water, thank god she’s not dead. While we’re able to laugh we also stop and recognize the severity of Molly’s state: she is totally alone while she loses her grip on reality. Cue Ray. While far younger, Ray seems to have recognized the world’s realities years before Molly. As she states so clearly, tiny soulless glasses atop her tiny nose: “It’s a harsh world”. And so she copes: trust no one, fend for yourself. If someone bails on you, get angry and move on. Stick to routine and let no one or thing get in your way. Not the most healthy way of coping with an absent mother and “vegetable” dad, but no one has cared enough to correct her. She’s used to controlling her life and tidying things in it so that she doesn't have to focus on the underlying mess of her lack of childhood or abundant loneliness. She compulsively cleans (she carries around her own personal soap bar) and rejects companionship (be it leaving ballet class early or firing any nanny who tries). But once she meets Molly, she eventually accepts change. The two learn to cope. When Molly jumps off a bridge, Ray takes her seriously, nurse her back to health, encourages Molly to heal her issues responsibly. Molly gives Ray the attention she deserves, validating her feelings of loneliness Ray previously rejected. The film balances tone phenomenally, presenting a serious moment where the audience stops for a moment to process what these young women are saying, forgetting that we are watching a chick flick (negative connotation carrying the rotten tomatoes score). And then the moment ends with a laugh- a swinging door to the face, a realization that the protagonist is standing in sewage. This is the reality of mental illness, at least one I can relate to: one moment there's not enough air in your lungs to process the mess in your mind, the next you realize you’re hyperventilating in a Ben & Jerry's bathroom. And that's kind of just funny. I’ve talked too much about this silly film apart of a genre I’ll defend to the ends of the earth, so I’ll leave you with this Brittany Murphy line (rest in fucking elegance, girl): “You know I saw this show once...about all these sick people. And the ones where their friends and families talked to them, they held on ten times longer than the ones left all alone.” And fuck. I really felt that. By Ryan Simpkins Let's talk Baby Driver. Came out on a Wednesday last summer’s June. Originally intended to get an August release but was pushed up after a positive reception at SXSW. Edgar Wright’s first American film with him at the helm as both writer and director. A movie I had been waiting for for months, if not years. (I’ll defend Wright as one of the most interesting directors alive today, utilizing his punchy editing and succinct sound design, along with every other medium exercised in filmmaking, to sell a joke. What a guy.) I was lucky enough to catch an advanced screening of the film the month before it’s release, the theater revving with electricity. People dancing in their seats to his iconic soundtrack, cheering for Baby to evade the police one more time, exploding when he succeeded to do so. Walking home from the theater felt like a dance, my friends and I spinning around to remind each other of that one scene we loved so much, jumping off tall curbsides in recounting that one song. I had never felt so amped by a film, so satisfied by something I had built up so much in my mind. Even Ansel Elgort was charming despite his history as a wooden plank in my eyes. Then, amid our excitement in original content and inspiration to make our own, my friend Nick said “The love story’s sort of... unrealistic, right?” At first, I defended it. I countered by explaining that it was a fairytale, it was classic retelling. Wright works to reinvent genre, to play on its tropes. He was exploring bank robbers and get away drivers in heist movies-- of course there had to be the agreeable girl to ride off into the sunset with. But I knew what Nick meant. And I knew my defense didn’t really matter. Sure, maybe Wright works to reinvent familiar genre, but here he had only reproduced myths of the feminine in characters flat and mimicking. Wright’s men leaped off the page, but his women weren’t even colored in. I have now seen Baby Driver six times: four in theaters and twice since I’ve bought it on iTunes. And every time my disappointment grows and astonishment fades as the female characters make the same mistakes, hit the same boring notes, and kiss the same men the way they always do, despite my mind willing them to do otherwise. While Wright shines in this showcase of his directorial skills, his film falters in his flat female characters who lack agency, personality, or originality, characterization practically pulled from a hat of love interest tropes. To sum it up, Baby Driver is a boys club. It’s music video meets heist film, story told by soundtrack songs played by Baby, our ears and eyes (and unavoidable male gaze). Elgort plays Baby, a sweet kid in a bad situation: he listens to iPod after iPod to deal with a hearing ailment, makes garageband like music in his free time, and misses his mom (played by breathy Sky Ferreira, cause, sure) who died when he was young. But in between making playlists and caring for his handicapped foster father (CJ Jones), Baby is forced to drive criminals away from robbed banks to pay off a debt to gang leader mastermind Doc (played by ~super yikes~ Kevin Spacey). Doc only chooses the best of the best for these gigs, he “never does a job with the exact same crew twice”, save for Baby (a testament to his talent). This plot ploy introduces us to several big bad bank robbers, such as lovers Buddy (Jon Hamm) and Darling (Eiza Gonzalez), as well as Jamie Foxx’s Bats (plus Flea is there at one point, cause why not). These colorful characters (literally characterized by colors black, lavender, and red) come together at the films climax for the ultimate unexpected heist-- but of course, now Baby wants out. He wants to escape with his girl-next-door “waitress girlfriend” Deborah (name like the Beck song, or the T-Rex one, played by Lily James). So Baby bails, or tries to, and runs for his life to achieve a dream of romance that sounds like lyrics to a Chainsmokers song: “to head west... in a car I can’t afford with a plan I don’t have: just me, music, and the road.” Throughout the film, Baby dreams of a 1950s fantasy: black and white as Deborah leans on a smooth car in a school girl skirt as Baby with his hair gelled up approaches. It’s simple and nostalgic, much like the rest of the film romanticizing American diners and classic rock. But this nostalgia reveals ignorance as Baby (and Wright) reminisce on a time of heightened heteronormativity and patriarchal control, the women in the film serving as 1950s pin-up girls, and nothing else. First, there’s Deborah. Poor, beautiful Deborah. Lily James does her best. She’s classic Manic Pixie, a term coined by Nathan Rabin to describe Dream Girls who “exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures". Their feelings often ignore, their character often prop to serve male counter points, revealing their inner feelings and motivating their plot rather than having an independent plot or arch of their own. We first meet Deborah on a tricked out coffee run where the Harlem Shuffle plays in Baby’s headphones, car horns and wall art signing along to the song. A quirky girl in cheerful yellow with big purple headphones catches Baby’s eye as she passes below a graffiti mural of heavenly clouds and a big red heart: there she is, that’s our love interest. With a coy smile to Baby before her look away, Deborah is pinned under the film’s thumb as a girl different from the rest, a girl who gets it, in the eyes of Baby, a girl who will be his girlfriend and nothing more. Deborah later enters the diner where he eats, dreamingly singing out the letters of his name to Carla Thomas’ tune “B..A...B...Y, ba-by”. She takes his order and just starts acting weird. She first notices his tape recording their conversation, a habit of his we’re familiar with, but one a stranger would see as crossing a line, right? Not Deborah. She picks it up and plays his game, speaking right into the tape’s mic. Sure. Rather than taking his order she begins to ramble, confessing suddenly her escapist dreams involving driving (omg, Baby drives) and listening to music (omg, Baby LOVES music). What has Deborah taking interest in this tight lipped, expressionless, monotoned (she’ll say “Mysterious”, I’ll say white bread) white boy is left unsaid, as female thoughts or rationale has no place in the film. And this immediate attraction is only the beginning of that issue. As the film goes on, Baby keeps secrets from Deborah and grows more dangerous and violent, lying to her about his personal life and work while putting her in these dangerous contexts. Deborah is threatened by his gang, witnesses him shoot a man, and still decides to run off with him. Keep in mind, they have only been on a date or two at this point in their relationship, yet Deborah is willing to give up her whole life to escape with him, knowing once they start running (from the police, from the gang) they’ll never stop. But what independent life is she giving up, really? The most we ever learn about our waitress is on one of her first dates with Baby in a laundromat (so domestic, wow). The two sit against machines spinning bright cycles of primary colors as their feet tap to the music playing from their shared headphones. They listen to a song with the same name as Baby’s new girlfriend (“Oh De-bo-ra, always look like a ze-b-ra” “Well I am wearing black-and-white so I guess you could call me Zebora” - and she’s funny too!) as he lip syncs along, knowing the words by heart, and watches a smiling Deborah bob her head. The camera pans around them the wash cycles behind them as they stand and spin around each other the same way to learn about where they’re from, what they’re like, all the while keeping their earbuds in place. The two stand close as Deborah leans against a washer, Baby standing over her. He tells her how his parents died. Deborah tells him she’s lost hers as well. Her eyes line with tears as she tells him “I don’t have much to keep me here anymore”, as if that’s Wright’s excuse. It’s honestly a lovely scene. It’s fresh and exciting, the audience able to feel the early first date jitters when you’re just getting to know someone you know you’ll fall in love with. But it’s as far into Deborah’s character as we get. Her orphaned backstory mirrors Baby’s, her simple dreams align with his, her only characterization is flirting with him and waiting on him, literally, both in the diner and in their lives, as she waits for him to drive off with her or waits for him on the outside of (spoiler alert) prison. Deborah serves as his yes-man, lacking any original character to serve anything other than his plot. The other female character we really meet is Darling, characterized by her beauty. Darling, younger than Buddy, her boyfriend and often seen sucking a lollipop, has a flirtatious air about her, laughing at the men with things get stiff, singing to Baby rather than threatening him. The male gaze is strongest concerning Darling, the film featuring a few direct shots of her hips as she walks away. She’s sort of not much more than the Hot Girl of the team. However, I give a bit more credit to Gonzalez in Baby than most people do. There’s a moment in the film where things get tense: an arms deal has gone wrong, lots of cops are dead, and Bats reveals how much of a loose cannon he is. No ones seeming to like each other very much. Bats has Baby pull into a gas station to raid the convenience store while Darling and Buddy sit in the back, Darlings legs draped over Buddy’s as she brings her face inches from his. She strokes his ego, reminding him of his violence towards men who threatened his girl, his relationship. “Remember that time you killed that guy, cause he looked at me funny?” she asks, Buddy nods. Darling cocks her head, eyes serious, and nearly whispers “Bats just looked at me funny”. I like to believe that both Darling and Gonzalez know what they’re doing here: they’re playing with dangerous men, performing the part of sex kitten to gain control, or a least have a little fun. But I know this is kind to the film and it’s treatment of Darling, as she too is just meant to serve the plot. Fastforward, final heist goes wrong, Baby’s on a run from the gang, the gang is on the run from the cops, and they all meet up at a musical shootout. Darling, for whatever reason, jumps from her cover and shoots off rounds in a fiery blaze. Of course, she dies, taking shots to the body to the tempo of Focus’ “Hocus Pocus”. Buddy yells in anguish, cursing Baby, sending him over the line from sweet-but-edgy father figure to fucking crazy violent bad guy. Her death motivates his descent into antagonism, providing a bad guy for Baby to contrast (proving to us that he is good) and defeat. But Darling’s death is not her own, it belongs to Buddy now, after all she did was show up, look hot, and die. (I just wanna say that as I write this in a coffee shop a white boy in a Baby Driver Jacket - black vest, white collar and sleeves - and dollar store black sunglasses walked in. The influence of this film presented in real time. I wonder if he hits on his waitresses.) I know this piece doesn’t sound like it, but I genuinely love Baby Driver. I truly believe it’s a feat in filmmaking to have an action film so well modernized, so grounded in this realm of fantasy that we can believe in, relate to, and root for. Wright’s editing and choreography are brilliantly repurposed for the sake of not just comedic timing but suspense, conflict. It represents characters with disabilities using actors who actually have them (CJ Jones is so so good) not as handicapped, but as people who move in stride, with Jones’ deaf character loving music in a deeper sense than auditorily because he feels it. Above all else, it’s fun. But this is why I think it’s all the more reason to recognize it for its faults. Imagine a Baby Driver I could watch without rolling my eyes, without a feeling of uncomfortability, without wanting to slap Deborah across the face and shake her out of her weird zombie drunk like state. I relate to Baby in its protagonists’ quirk and charm, and am then alienated by the way he looks at women like cardboard. Imagine if I could have my cake and eat it too. by Ryan Simpkins I have such a crush on Carey Mulligan. She’s perfected the role of the difficult woman, finding understanding in characters like hateable Daisy Buchanan or obnoxious Kitty Bennet. She cheats on Justin Timberlake in Inside Llewyn Davis, getting pregnant with broke-as-shit Oscar Isaac’s unwanted kid. Before that she cheated on Oscar Isaac with Ryan Gosling in Drive, playing a love interest with thought and agency amidst a gang war (while those characters are often left unexplored). She is always, always so thoughtful, and likable in a way despite the shit her characters pull. Or maybe I’m just biased. (I cut my waist length hair to a bob because of her when I was 16. Sometimes people say I almost look like her and I die.) But in all of these roles she is second to a man, her insanity reflected against their stoic performances. She’s been wife to several Hollywood hotties (I just named four counting DiCaprio as Gatsby), but so rarely is she able to claim these characters in their own light. Finally, she has been given the chance. Any critic will tell you, Wildlife is Mulligan’s movie. Penned by indie film power couple Zoe Kazan and Paul Dano, and the directorial debut of the latter, Wildlife explores the implosion of a nuclear family in 1960s small town Montana against the backdrop of a roaring wildfire. Mulligan’s Jeanette is wife to Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal, also killer) and mother to Joe (Ed Oxenbould, pretty much Paul Dano age 14), picture perfect for the first ten minutes. Joe plays football, Jerry works, and Jeanette makes the meals, all three coming together to listen to the game on the radio at the end of the day. Jerry has moved his family from town to town amidst a cycle of being hired and let go from seemingly every job. Jeanette has supported her husband through this, used to meal prep and job loss, but is now tired of the constant moving. Upon his most recent lost job fresh from the move to Montana, Jeanette and Joe are resistant to another move and willing to make things here work. The two get jobs as the patriarch drinks late into the night and sleeps in his car, desperate for a change of pace but unwilling to set the wheels in motion. Finally, he finds work fighting the forest fire that threatens the town, a job recognized as impossible as they only dig trenches to keep it from spreading and wait for the snow to fall, for nature to control itself. Jeanette loses it. She fights him, guilts him, tells him he’s only running away again, this time leaving his family behind. Joe watches his parents yell at each other for maybe the first time. And still, Jerry leaves. Jeanette is left to fall to her own devices, thrashing against social norms as the family life she worked towards falls to ashes around her. Yet Gyllenhaal is not the villain of this story. He too is just a player in what the 1950’s asked of its young men. The family has simply fallen victim to itself: pressures of performity and social construction building people into a dollhouse of patriarchal roles and female submission. What is so brilliant about Kazan and Dano’s script paired with the talents of Mulligan is its recognition of Friedanian stresses on nuclear housewives as the mental illness that it is, the pressure of forced motherhood turning women sick. A family that never wanted to be a family can’t do anything but burn. The film is set just a few years before second wave feminism was really set into motion. In 1963, Betty Friedan published her Feminine Mystique. The book explores a “problem with no name” living within American housewives. Young women with husband and children felt trapped within the walls of their homes, submitting themselves to housework and chores, serving their family as if that was enough to serve themselves. These women felt guilty hoarding these feelings, resenting their loved ones as they were confined to a feminity of submission. Friedan defines this problem, letting these young (mostly white, middle class, all American) women know that they were not alone, that they were not crazy, that their feelings of entrapment were valid and the system ushering them into these roles was unjust. A bit of Friedan’s theory can be credited to Simone de Beauvoir’s exploration of what she calls The Second Sex (aka the construction of femininity as a gender made submissive), a major bit of foundation for feminist theory. De Beauvoir credits the societal pressures on women to reproduce and raise a family as a means of society’s domination and use of women. Famed Judith Butler based her own feminist theory on both these writers. If you’ve taken any sociology class I’m sure you’re familiar with her idea that gender is performative. We are simply policing ourselves to act out prescribed notions of gender archetypes, subconsciously acting the way we believe a society would want us to. We see all of these theories exhibited in Wildlife. Mulligan’s Jeanette acts as a model example of a woman hindered by what these theories define. She works to act like the perfect housewife, submitting to the controls of a patriarchal family, all the while an unnamed problem boiling beneath her skin. Jeanette was a young mother, as so many women in the period were. She’s only 34 raising her 14-year-old son, making her 20 when she had Jerry’s baby. She dropped out of college, telling her son she practically left the school before her time there began, doing so presumably to raise this family. Jeanette is nostalgic for her youth before motherhood, telling Joe stories of the cowboy bars she used to linger in, wearing outfits from her “pageant queen” days. “It’s probably nice to know your parents were once not your parents,” she says, swaying her hips to music like she used to. Jeanette was pushed into motherhood before her time, before her chance to explore her potential granted with a college education and degree. She fell into this role amidst exciting young adulthood, opportunities endless with the whole world ahead of her. All of that stopped short by a pregnancy that may have easily been accidental. But Jeanette seemed to have taken this in stride, rolling with the punches and claiming this role as her official title, working to look like a woman in a ‘50s Jell-O advertisement. Jeanette puts work into her image, Mulligan playing the roll of pin up housewife perfectly for the film’s first 15 minutes. Her hair is huge and overdone, makeup spotless, dresses for cookbook family dinner like it’s a ball, in an appearance that would have taken hours to complete. While Jerry is putting hours in at work, jobless Jeanette is working hard for this image. She masks money trouble, excusing a check bouncing at her son’s school by explaining a bank switch that came with the move (sounds fake but ok, Carey). She understands the importance of upholding the household, helping her son with homework and encouraging her husband despite his job loss, playing her part in the picture perfect family. But this gets tiresome, and it’s clear Jeanette wants more. As soon as the opportunity arises, Jeanette offers to go back to work. She mentions her old job as a substitute early in the film, a hint of longing in her voice as she offers to the high school secretary how nice it must be to be surrounded by young people, “all that spirit”. As soon as Jerry loses his job, she mentions the possibility of her getting her own, a proposal framed as an offer that’s really a statement to Mulligan. She mentions it at least three times in half a scene, remaining her composure against her dejected, careless husband, housewife hair still perfect. She then sets out in a fancy fit to go push herself into the workforce, unrelenting in one office that gives her several “no”s until she finally gets a yes. Jeanette does find a sense of liberation in her work teaching swimming classes at the Y, discovering a social circle of young working women living independently at the “Helen apartments”, housing she speaks of with longing once her husband leaves. She finds a bit of room to breathe in working in the public sphere, but that begins to change when her husband up and leaves. Her husband’s running off to the fires leaves Jeanette fuming. The day he’s gone there is a clear change: she is cold, curt, distant. Joe awakes late the morning after his father leaves, realizing he’s late for school. He moves to the living room where his mother stands in an evening gown, leaning into a mirror to apply her lipstick. She offers Joe no explanation, only telling him she needs to care for the two of them now that his father has “abandoned” them. He’s still in shock, as if it’s a dream he’s still trying to wake from. “You’re wasting your life standing there watching me, sweetheart,” she tells him. This is not the woman who kissed his head and helped him with his homework, this is a woman working to adapt like a confused animal caught in a fire. She continuously reminds Joe that she is the one who’s stayed with him while his father up and left, even taking Joe to the hills too close to the fire to see the destruction while not allowing him a chance to look for his father among the fighters. Jeanette is itching with a slight jealousy, telling Joe “I think your father has a woman out here”. But her jealousy is more than that. Jerry had the freedom to up and leave, to explore his own path in the face of confusion without society judging him for it. Jerry, a man who got his college girlfriend pregnant and then corralled her into a family home, has now left his family to go live on the edge of life. And Jeanette cannot stand it, as she was forced to sacrifice her youth, her potential, to pull together the appearance of family that her husband is able to so carelessly leave behind. She is forced to stay, while there’s always been a longing for more behind her made up eyes. But in the same way a paranoid partner worries their lover is unfaithful because they have that tendencies within them, Jeanette projects the term “abandonment” onto Jerry’s actions countlessly, as if seeing her own insecurities and desires in what he’s doing. She lashes out in independence, shaking off her motherly responsibilities of making dinner for her son and waking him up for school to go live her own life amongst young working women and powerful men who want her. She’s unfaithful to her husband. Jeanette acts dangerously, something within her snapping that is more than jealousy and betrayal, but a mental illness that’s boiled over. Behavior exhibited by Mulligan’s young housewife is crazed. Jeanette flies between massive mood swings, dancing and flirting in her pageantry gown one minute before becoming “irritable” the next, speeding to the door. She is aggressive and paranoid, turning the corner after showing her lover out to find Joe and slap him, hard, an energy found in a moment of shock. The audience moves slowly through the halls with Joe, finding his mother’s clothes strewn about a softly lit room, unsure when his father will return as we hear the front door shut. Is it his father come to find her betrayal? We quickly realize it’s only her with her slap, but it’s clear she had the same concern. Jeanette drinks excessively, putting herself in uncomfortable positions with men she doesn’t care for but sleeps with anyway (it’s implied the older man provides her with a financial support), drinking to ease herself into the situation. A strange scene all too long - to make sure we’re as upset as Joe, who was dragged along - plays out where Jeanette goes to dinner with the rich and wrinkled Warren Miller, a man very powerful in town. She wears a dress that’s too nice and drinks his expensive booze, flirting with him while her son sits across the table and watches. Earlier, Joe asked his mother if she liked the man, a man she gave praise to for being “powerful, with powerful friends”. Her look told us she knew Miller as a revolting man who holds that power above the heads of others. And yet she goes back on this judgement from moment to moment, between disgust and desperation. Perhaps she does this because she is used to surrendering herself to male dominance, Jerry having called the shots and moved the family around for so long. In his absence she is angry and confused and works to fill his role with a man she uses for his money and power. This behavior is erratic and unchartable, the audience and Joe never sure what will set her off when, whether or not she’ll be home in the morning or be back for dinner at night, unsure if she’ll greet us with a smile or just look past us to the wall behind our heads. After a drunken mistake she sits in the car and works to breathe through her tears, holding her hands to her head and choking out “I feel like I need to wake up”. Joe, sitting next to her, asks “Mom?”. And she turns, blankly, as if she forgot he was there, before furrowing her brow and putting on a slow smile, juxtaposing the empty look in her wet eyes. Now, reviews love Carey, as do I, but some take issue with how quickly she turns. She wears a beehive and makes breakfast in one scene and then suddenly in the next it’s like she’s gone. But I think this is misunderstood as a “turn” at all. From the film’s beginning, Mulligan mastered a smile below sad eyes, masking an upset for a greater desire beneath curved lips painted red. Her eyes will tell us of her confusion, of her disappointment with her husband, of her want for work contrasting the way she asks if she should apply for jobs like a delicate question. But above all, the men will see her smile. Jeanette did not turn - for this illness has been within her all along, only now finding room to become unleashed. By Ryan Simpkins The day had been shit. I was in bed, angry with men and anxious about something, wanting some escape from a bad mood. My best friend, Cloe, was in a similar headspace. We usually worked to shake off the shitty days by watching some primo teenaged content, like Twin-Peaks-wanna-be Riverdale or sexless romance Twilight. So we decided to bunker down, drink some wine, and watch Megan Fox be hot and eat boys. Upon its release in 2009, Jennifer’s Body was written off as a money grabber without merit. Hollywood was not yet fatigued with Megan Fox, still shaping her into the sex appeal they wanted her to be as 14 year old boys drooling in their Transformers pajamas. Amanda Seyfried was fresh from her Mamma Mia fame, looking for an edgy role to oppose that of the “young and sweet”. The film was prime for Hot Topic promo as pop punk boy band Panic! At The Disco adorned the soundtrack, and a Fall Out Boy was poster prominently featured in the very first scene. Hollywood was tapping into emo girls’ dreams of vampire boyfriends and Paramore love songs. Critics shut Jennifer down before its release as a movie about girls made for boys who’d pay money to watch them kiss. It looked like just another teen movie. And director Karyn Kusama was keenly aware. The film centers on closeted gal pals Needy and Jennifer (played by Seyfried and Fox). The two mimic a stereotype like that found in Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me”, the short skirted cheer captain and the girl on the bleachers; the difference here being they’re best friends. The girls have a complicated relationship, balancing intense admiration with power play, one knocking the other down or picking her up depending on which ego craves when. This back and forth reaches its peak when eyeliner wearing indie band Low Shoulder comes to town. The boy band abducts slurring, drunken Jennifer and sacrifice her supposedly virgin soul to Satan in exchange for becoming “...rich and awesome, like that guy from Maroon 5.” The band is mistaken, however, as our high school queen bee isn’t even a “backdoor virgin,” and so their attempted sacrifice results in Jennifer’s return to the mortal world as a flesh eating demon. She enacts violence on vulnerable teenage boys, luring them with sex before eating them alive. Needy comes to understand Jennifer is now more than a teenage girl; she has become something of hell itself. And so Needy must work to save the innocent from her murderous girlfriend, a plight explored with the sensitivity of a teenage girl’s. The tone is angry and jealous and rash because it’s one of heartbreak as Needy and Jennifer’s relationship is strained against heteronormativity, sexual ego, and violence. The film casts Fox perfectly as a young girl sexualized by the grown men around her: her youth and sexual energy is taken advantage of by older men with authoritative status. In Jennifer, it’s the band or the deputy sheriff. In Fox’s young career, it’s men like Michael Bay. Kusama’s casting of Fox is vengeful. Jennifer uses male attraction lure them in, to devour them, to grow stronger, while performative heterosexuality allows her to enjoy her romance with Needy privately and intimately. Jennifer takes advantage of the heteropatriarchy in place, letting it empower her while enacting a subtle but deadly queer resistance. I do not know if Kusama is queer herself, but she sure knows how to make a movie gay as hell. Jennifer lives and breathes Camp, an aesthetic of exaggeration and difference prominent in proudly gay movies. The film fully embraces young homosexuality with iconic Diablo Cody one liners on “going both ways” (murdering boys and girls) or being “totally lesbi-gay”. The film handles queer sex in a different light than that of straight couples. A strange scene plays out where Needy has sex with her boyfriend, Chip, for the first time. This is edited alongside a scene where Jennifer lures in her latest victim, the school’s resident emo and Needy’s perhaps closer-than-friends pal Colin. Needy’s sex starts innocently enough with an awkward condom fumble and creaking mattress box springs, lights fully on. Creaking floorboards and squeaking rats surround Jennifer and Colin as she seduces him, stabs him, and eats him alive. Visions of this come to Needy mid-copulation, seeing Jennifer atop Colin, eating his throat out, her chin wet with blood. Needy screams in horror, and while Chip reacts, he doesn’t stop, an almost proud look on his face, as though PornHub taught her painful noises signified pleasure. The hetero sex scenes are awkward and violent, ending in either pain or death. The moments shared between Jennifer and Needy, however, are sensual and intimate. Lights are dimmed and the camera is close while catching skin against skin or a hand running through hair. The moment between them doesn’t happen because it’s supposed to (as a boyfriend and girlfriend will eventually have sex) or because it has to (as Jennifer’s life depends on consuming her male partners). They do it because they want to. Critics misunderstood the film by seeing it from the male perspective, expecting smut for teenage boys rather than the antithesis of that: a genuine exploration of gay girls. While the film’s marketing may not have targeted such an audience, Kusama knows she is making a movie for women. She understands their paranoia and desire, working to represent them in a genre that usually throws them away. One liners welcome a female knowingness as Jennifer is impaled with a pole and retorts by asking for a tampon. Other moments are darker, playing on female anxieties. The image of a foggy field where a man stalks a woman is familiar. Kusama flips this, depicting an unknowing Chip alone at night with an out-of-focus Jennifer emerging behind him from the fog, her white dress billowing behind her. The camera implements a female gaze here aligned with a teenage girl, giving a certain satisfaction with the fear. A teenage girl knows never to walk alone at night. We know not to follow strange men into forests or abandoned houses or their dark vans; we know what’s on the other side. Even if pre-demon Jennifer knew this too, a famous man she admired took advantage of her intoxication and led her to what waits there. He and his band abduct her, driving her to the middle of the woods to take advantage of her virginity. The fear of sexual assault is as real to the characters in the film as it is to the women watching it, Jennifer even asking if r*pe is their intention. While the intention of the band differs, the intention of the director is to invoke this primal femme fear, all too familiar with warnings against strange men in vans. Jennifer is tied to a tree, alone with only her assaultants. The men laugh and joke as she screams for help. They even sing as they stab her to death before her body drops into a ravine. But Jennifer’s impurity saves her from death, yet another horror trope Kusama turns on its head. And so we watch as she wreaks havoc on a society of men who cornered her into the hot girl role, exploring a type of reverse rape-culture (a term coined by critic Kristy Puchko). Jennifer has developed a bit of a cult status since its flat 2009 release. I remember rolling my eyes at it then when I was only 11, turning any curiosity around Jennifer and her body into resentment towards “airhead” hot girls. That began to shift when I got to high school, the cool queer girl I looked up to talking about the film like white boys talk Mission Impossible. I became cautiously possessed for a moment, checking stills and reading the Wikipedia plot synopsis like I did for most horror movies I was too scared to see. I proudly watched the official “New Perspective” music video where Brendon Urie walked through the halls of my very own high school, intercut with clips of Megan Fox strutting the fictional halls of her’s. I don’t know why it took me till this October to decide to watch the film itself, post my misdirected Megan Fox hatred, post my pop punk phase. Vox recently published an article on the film’s newfound cult status, claiming the people of 2009 weren’t ready for Cody and Kusama’s feminist zom-com. I disagree. I just think the hate around the film was “invented by the boy-run media to make us seem like we’re crazy” for wanting to watch a hot zombie kill dudes and kiss ladies. But maybe that’s just me. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|