|

by Quentin Freeman Some schools have snow days. So far this year, UC Berkeley prefers to spice it up with Our State is On Fire Days, Worldwide Epidemic Days, and All Our Grad Students are On Strike For Livable Wages Days. Whoever said school was boring? The UC Berkeley grad students voted to go on a full strike starting Monday, March 16, in demand of a cost of living adjustment (COLA) and in solidarity with the 4 other UC campuses currently on strike. Starting Monday, not only will our classes be virtual, but if your GSI is one of the students on strike, it’s no guarantee that they’ll happen at all. Wondering what to do with yourself to fill the time (besides support your GSIs and wash your hands)? Spring break trip to Italy get cancelled? A little freaked out by campus’s new pre-apocalyptic vibe? Consider the following:

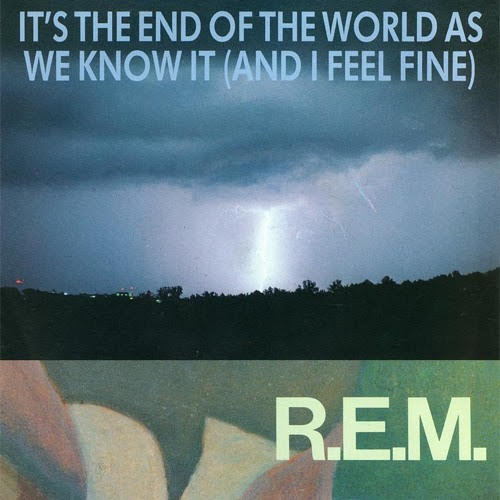

Get outside! Berkeley is home to some delightful hiking trails, and nature is only a walk, bike ride, bus, or BART away. Work out those lungs and get some Vitamin D, and word on the streets is that trees can’t spread the virus. Short of using our cancelled classes as an opportunity to live out your hermit-in-the-forest dreams, check out the Fire Trails for some local action, or take the 67 bus to Tilden, where you can stroll through redwoods and around lakes. Want to get out of Berkeley? Head to Briones Regional Park just over the Berkeley Hills for some beatific rolling hills, or make the longer trek to Point Reyes National Seashore-- accessible by public transit! Listen to Radioactive by Imagine Dragons. Yeah, it might not be the most uplifting song to go with the crumbling university, but what a banger. Get yourself fired up to take on whatever the world wants to throw at you, from glitching internet on your Zoom lecture to a full-scale, nuclear-fallout-style apocalypse. Teach yourself a new skill or hobby. Maybe you’ve always wanted to learn to play the guitar, or speak Gaelic! Learn to embroider, identify edible plants, practice your survival skills, or perfect your latte art. Maybe take up woodworking so you can build that off the grid cabin of your dreams! Now’s your chance to memorize all the lyrics to It’s the End of the World As We Know It by R.E.M.! Feeling romantic? Hozier’s Wasteland, Baby! is the ultimate album for when it’s the end of the world, but you’re also totally in love. Highlights from the record include No Plan, complete with driving beat and nihilistic discussion of how there is in fact no plan for the universe, and everything will at some point return to darkness-- but at least you’re watching the final sunset with your girl! A little more on the acoustic side of things, check out the titular track, Wasteland, Baby: a soft, delicate ballad with lyrics like poetry. I mean, “And the day that we watch the death of the sun / that the cloud and the cold and those jeans you have on / That you gaze unafraid as they saw from the city ruins /Wasteland, baby / I'm in love / I’m in love with you” -- nobody ever said the end of days had to be a turn off. The album is full of great date ideas for the end of the world, if you need any inspiration. Maybe don’t read The Stand by Stephen King unless you really want to lean into this whole pandemic thing. A nearly thousand page post-apocalyptic horror epic, The Stand is a fabulous way to kill a couple dozen hours. Its intricate web of characters, slightly disturbing world-building, and unfortunately very timely premise of apocalypse-by-disease keeps you riveted and a tad freaked out-- but very grateful that our own pandemic is not quite as horrifying and end-of-the-world-inducing as the fictional virus in the novel. However you decide to fill your time, don’t forget that in reality, COVID-19 isn’t the harbinger of the end of days; as truly unfortunate as this situation is, it’s only temporary. Wash your hands, be careful, go home if you want, but don’t fall prey to the panic. See you on Zoom!

0 Comments

Most of the work I do for my architecture classes is essentially just a very extra version of arts and crafts: a plan or a section? Literally a more technical drawing. A model? More like paper and cardboard.

Drawing and crafting are two things I love to do. But why is it so much more painful when it’s for an architecture studio? At first, I thought the dread and stress was a result of being graded on the things I produced. After all, as one of my GSIs wisely stated the other day in office hours: “everything would be more fun if there were no stakes.” But then I thought back to high school (a period of time that I have blocked out most memories from) and remembered the four years of art classes I took, which were the least stressful classes I ever took in those four hellish years. And sure, sometimes I was worried about what my teachers thought of my work and whether that work merited a coveted “A.” But the majority of the feelings I associate with these art classes are positive and very relaxed-- laughing with friends, experimenting with different media, listening to music, getting messy. I was getting to make things that I enjoyed making, where the end result was the result of a creative exploration that wasn’t stifled by a barrage of technical requirements and critiqued into a jargon-laden oblivion. I was creating, not producing. The idea of production in architecture, the way I understand it, voids the creation of architectural work-- which is basically a form of art-- of any actual creativity. Designers in an architecture firm are literally part of a department called “production.” You’re resigned to drawing the same things over and over again: insulation, floor finishes, concrete slabs, glazing units. But somehow in the workplace it’s still more tolerable than it is in academia. Because in architecture school even mastering those details is not enough. You have to have an argument for everything, a technical aesthetic rationale behind every stroke and lineweight on your drawing or piece of paper in your model. You are hardly ever allowed to say you designed something because it “just looks better” (unless, of course, you have a moderately empathetic professor.) And, look, I get it. The study of architecture can no longer be the early Bauhaus pre-hippie trip into expressionism and radical thought. It has a reputation to maintain. But why must that reputation come at the cost of any creativity in the study of architecture? Why is every creative idea critiqued into oblivion? (And if it hasn’t been yet, it will be, so much so that you’ll never want to try anything radical again.) Assignments are given under the guise of freedom, yet when you try to take advantage of that freedom, a critic will find something wrong with what you’ve done. Because unlike in art, the designs you produce as an architecture student must comply with the laws of physics and construction, most of which, frankly, you have little to no real knowledge of.* And because of that, it becomes incredibly difficult to produce any work without strict guidelines, because the fear of being criticized, of the unknown is utterly crippling. Fear doesn’t breed creativity. *I’m not saying that art school is easy either, folks. The comparison is based on my own personal experience having taken art classes for over ten years before college. So what exactly am I looking for instead? It seems unlikely that the pedagogy of architecture school (or the study of any other subject in which “learning” is pretty transparently fear-based) is going to change anytime soon, especially since most architecture teachers subscribe to the “well that’s the way I learned it, so now you have to suffer through it too” philosophy. Maybe this is just part of the process of pursuing something you thought you always wanted to do (I’ve wanted to become an architect since I was eight). But I also feel like there’s a point at which academics really need to step back and question whether or not their methods are actually working. Is forcing students to work 18-hour days on little sleep without time to properly feed themselves really fostering an environment in which students are actually producing good work and learning? Based on how the quality of my work has declined since I started junior year, I think not. And if someone comes at me with the classic “well, they’re just preparing you for the real world” nonsense-- well, maybe the “real world” doesn’t need to be based on fear and workaholism. I don’t know. Just a thought. by Lucas Fink [spoiler alert!]

Central to Mark Fisher’s theorizations of late capitalism is his emphasis on cultural stagnation and the resultant increase in reliance upon resurrected cultural forms. Nowhere is such a dearth of genuine novelty more apparent than in J.J. Abrams’ Star Wars: The Force Awakens, a film that strays a bit too close to being little more than a beat-by-beat retelling of A New Hope. A force-sensitive teenager on a desert planet is uprooted when she meets a droid carrying sensitive information and is swept up into a galactic civil war, meeting a surrogate father who dies at the end and aiding in the destruction of a massive spherical space station which is blown up after a trench run. I love this movie, but not for its originality. I also really love The Last Jedi, which respectfully and thoroughly inverts the predictability of its predecessor, unabashedly exploding convention and leaving in its wake new vistas of possibility I never thought I’d see in the Star Wars universe. Once every blue moon, the system will glitch and release something so self-aware and subversive that its very existence is one of schizophrenic tension. Why in the hell did Disney produce a movie whose fundamental themes call into question the system on which Disney subsists? I don’t know, but when these glitches in the matrix happen, I get happy. Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi is disillusioned and curmudgeonly, denouncing the elitism and bourgeois hubris of the old Jedi Order as a result of which Emperor Palpatine came to power. Poe Dameron learns it’s okay to defer to a female authority figure and that his self-worth and identity should not be predicated on a toxic conception of masculinity that consists of reckless, selfish, fame-starved individuality. Finn learns from Rose that there is an overclass of absurdly rich war-profiteering assholes who supply weapons to both the bad and good guys and presumably have been doing so for a while, thus helping to produce and perpetuate the cycle of conflict to which the Star Wars galaxy has been condemned for thousands of years. And then Kylo Ren fucking kills Supreme Leader Snoke (also known as Walmart Palpatine) and for three of the most exhilerating minutes in all of cinema we get to witness a fight scene - so well shot and choreographed it’s unfair - between the new Rey-Kylo alliance and Snoke’s Praetorian Guard during which we, while admiring the spectacle, contemplate astonishedly and frantically what in the fuck is going to happen next. Will Kylo turn good? Will Rey turn bad? What do the terms good and bad even mean anymore in this new realm of moral blurriness in which we suddenly find ourselves? Watching that moment in theatres, I felt something I never thought I would feel while watching a winter blockbuster produced by Disney that’s the eighth installment in a franchise: the promise of something genuinely new. Something interesting and thematically rich and shockingly subversive that all the while manages to enhance my appreciation for and enrich my understanding of the characters I’m already familiar with. I felt giddy and surprised and incredibly happy. Mark Fisher was a brilliant anticapitalist philosopher, cultural critic, and continental theorist. He took his life in 2017. Before his abrupt and deeply tragic death, Mark gifted us with some of the most lucidly and passionately articulated theorizations of life in modernity, of life in late digital capitalism. His writings are honest, personal, sad, scathing, funny, and often pessimistic, and yet are subtly - but unmistakably - underlined with optimism, a hope that Mark found harder and harder to sustain. For Mark, life in modernity is characterized by a nebulous malaise, in part engendered by the inability of culture to produce anything actually new. Because capitalism presents itself as the last form of social and economic organization, as the end of history, it evacuates the future. There is no future, because capitalism is eternal and inevitable; it is the way things have always been and the way things always will be. In such conditions, art becomes starved of novelty and as such is forced to become parasitic, leeching off of the trends of the past. If a time-traveller played Arctic Monkeys or The Drums or The Strokes at a party in the 1980s, no one would notice. Nirvana and Joy Division t-shirts are easier to find and purchase than any merchandise from a contemporary artist. Only 4 out of every 10 movies released between 2005 and 2014 had wholly original scripts. The Last Jedi did not have an original script; it was the eighth movie in a franchise now owned by a megacorporation. And yet, somehow, the movie constitutes a rupture in the fabric of the possible. It constitutes the exact thing Mark calls for at the end of his seminal work Capitalist Realism: “The long, dark night of the end of history has to be grasped as an enormous opportunity. The very oppressive pervasiveness of capitalist realism means that even glimmers of alternative political and economic possibilities can have a disproportionately great effect. The tiniest event can tear a hole in the grey curtain of reaction which has marked the horizons of possibility under capitalist realism. From a situation in which nothing can happen, suddenly anything is possible again.” The Last Jedi is that glimmer, that tiny event which shatters the imposed limits of capitalist realism and thus renders anything possible. I wish Mark could have seen it. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|