|

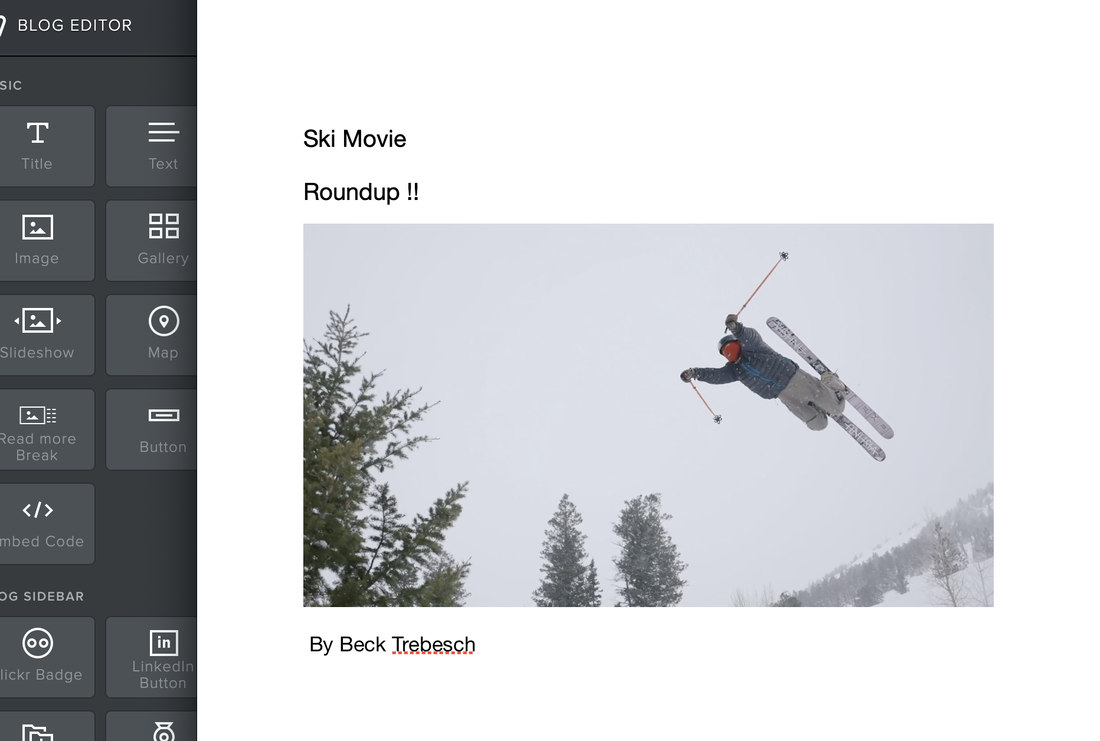

by Beck Trebesch This fall has been a distinctly democratic one for the ski movie industry, with a seemingly unprecedented number of flicks dropping for free on Newschoolers, skiing’s famed internet forum, or YouTube. I, the diligent skier I am, have been doing my best to keep up as the mid-sixties palm tree balm of Northern California intensifies my lust for waist deep snow, kinked handrails, and cork 3 safeties. With there being so many exciting, independently created films available, I felt it was only right to compile a compendium of the best the sport has had to offer ahead of the new season.

Entourage - YAKTV. (Bozeman, MT, USA) What the fuck is a YAKTV, you might ask? Is that some strange, out of pocket Barstool Sports reference that I’m just not getting? Thankfully, it’s not but unfortunately, it does stand for “You Already Know the Vibes.” And I did already know the vibes going into this one, following my scathing review of Entourage’s last film Collage. To my surprise and enjoyment, YAKTV. was a seriously notable improvement on the hodge podge, gimmick fest that was the last installment. The editing was more to the point, the filming made more sense, the skiing went harder; I couldn’t help but enjoy this 24 min helping from the crew. I would also like to commend Entourage’s successful pursuit of debuting the film at the Rialto Theater in Bozeman (theater debuts are a theme for this year). With our internet feeds being so saturated with content day in and day out, attaching a film to a public, tangible, lived experience, especially one where a large portion of the Bozeman community is participating, is seriously valuable in making this art meaningful, inclusive, and sustainable. Carnage - Wasted Potential (Bozeman, MT, USA) In my piece about Collage, last year I was going to cite Carnage’s last film, Subject to Change, as the beautiful, well-formed antithesis but time prevented me. A year on and the Carnage crew are still delivering gritty, unfiltered yet truly heartfelt productions to the absolute diehards of Bozeman’s freeride skiing population. Spitting with personality like Swift after a healthy hog of Copenhagen, this is the filmic equivalent to going to a Montana rodeo and successfully hijacking a bucking bronco or, more appropriately, Fritz’ snowmobile (sled in the local vernacular) erupting in flame at the start of the movie. Music is as important as ever in the extreme sport edit landscape and Wasted Potential exceeds with its eclectic employment of punk, metal, nu metal (let’s go), 2000’s hip hop, and alternative dance, pairing carnage to cacophony, smooth snowriding to silky synths, and Rage Against the Machine with the gnarliest sled segment in recent memory. There is such a consistent energy throughout this movie that materialized by the rough showmanship by the guys at the premier which I was lucky enough to go to in Bozeman the day before my 21st birthday. The after party was pretty fun, too… SNP MT - So Not Pro (Missoula, Montana, USA) To round out our Montana entries for this year is Missoula/Bozeman based crew SNP MT and their film, So Not Pro. With the other two Montana offerings fitting into a more classic ski film standard in regards to camera work and song choice, So Not Pro felt like it was more heavily informed by elements of skateboard/street culture. This was evidenced in stand alone shots, grungy but varied soundtrack, and the emphasis on urban skiing. For those who know William Strobeck’s style, characterized by slow frame rates, intense zooms, and straight forward angles, then Grant Larson’s undertaking becomes all the more recognizable as a tribute, worship even to that culture of videography. This was a super fun watch, with all the boys chipping in with big drops, precise rail sliding, big grins, and bone crushing slams across the 37 minute run time. They premiered this not once, not twice, but three times in Bozeman, Missoula, and Boulder, CO and for good reason. The public needs to see this. Deviate - Good Luck (filmed in Wyoming and Idaho) Here we shift gears from the up and coming amateur to the established pro. X Games medalists and famed stylers Jossi Wells and Torin Yater-Wallace teamed up with fellow pros Chris Logan, Birk Irving, and Cody LaPlante to put together an effortless package of backcountry booters, supple pillows, and jagged spines. It’s just a good, honest flick in ski movie terms. Nothing groundbreaking shot-wise, music-wise, vibe-wise. I can commend it for prompting me to say “wow, that’s big” on multiple occasions but in it being so clean (it is a Redbull sponsored project), so non-confrontational, so conventional, it didn’t quite stick with me like the other ones on this list did. There’s no doubt Chris Logan has the craziest cork 7 japan axis on the market right now but bottom line, I wish this one had a little more bite. Child Labor - Take 3 (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) Do you like watching grown men wearing beanies and smoking proper slam into asphalt streets and concrete walls covered with a vague amount of ice and snow? Do you need an education in style? Do you like Death Grips? Child Labor’s Take 3 has you covered in all departments in their new full length. The Utah crew are back with some of the best ACL-crunching, mind bending urban skiing in the amateur field. Cal Carson continues to be an absolute magician, Brolf got the Yung Lean makeover cut, Dakota is seen wearing a helmet, and Bennie is hippity hopping his way through Mormon country with ease; there’s a serious mystique about this crew embodied by Bennie emerging from a manhole cover to then hit a rail. The fisheye camera and nimble follow cams are serving these boys well too. My only gripe with this one is that while they took some really admirable risks with the soundtrack (Death Grips among multiple mashups and genre fusions), it did kinda kill the momentum of the film compared to their last one, Don’t Fret. But… Do I want them to change? Fuck no. Keep these children toiling away. Forre - Forrmula (Ruka, Finland) We round out with one of two international films I wanted to include in this year’s roundup and this one cannot, CANNOT be slept on. Probably the most strikingly beautiful film on the list, the Forre boys take to the grand streets of Finland and inject their own unique brand of technicality, style, and all out disregard for safety into the urban landscape. The amount of one of a kind features and spots they found in this movie might be a record breaking first for any ski movie I’ve ever seen. It’s not everyday you see someone grind a public sculpture made of abstract shapes or jump out of a 3 story graffiti-soaked, abandoned warehouse to near dead flat. Watching public urban form take center stage in this masterpiece was really refreshing. Also, the variety in everyone’s individual style which manifests in some seriously diverse trick selection leads to a dynamic yet compact experience. This really is the skier’s ski movie and there’s no doubt Forrmula was well worth the 10 dollars I paid for it. Suede - Rip in Pieces (Stockholm, Sweden) Rip in Pieces is not a mournful affair. Far from it. It’s celebratory. It’s innovative. It’s artful. Filmer/editor Emil Larssen combines one part patience, one part nimbleness to create a really, really fluid set of stunning skiing vignettes, spearheaded by our main cast of characters for the first 20 minutes. The introduction is truly something to behold. The Aegan blue ice graphic melts seamlessly into a slowly zooming shot of the Swedish backcountry, a temporal tribute to the environment, the molecules that make the sport possible. Filmic properties aside, the skiing in this movie is so fun to watch. These guys know their way around a ski. Nose, tail, edge, base; all parts got adequate attention on a series of urban features where just when you think the line or the trick is over, something else pops out. The Suede boys might not be going as big as some of their counterparts on this list but they make up for it with ingenuity and commitment to doing the right trick at the right time. I mean I don’t know I’ve ever seen a cork 7 lead safety look so goddamn good. Can’t wait for the next one. Entourage - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F25VakhuTgQ Carnage - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTG_j33QSow&t=1314s SNP - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ot0of6nuaTA&t=1303s Deviate - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPU1a9y1nNg&t=1152s Child Labor - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2mOtYThSAE Forre (not free) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VtLEczD4ZA&t=657s Suede - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4bUkTTr1iE&t=3s

0 Comments

by Natalia Macias weave stories

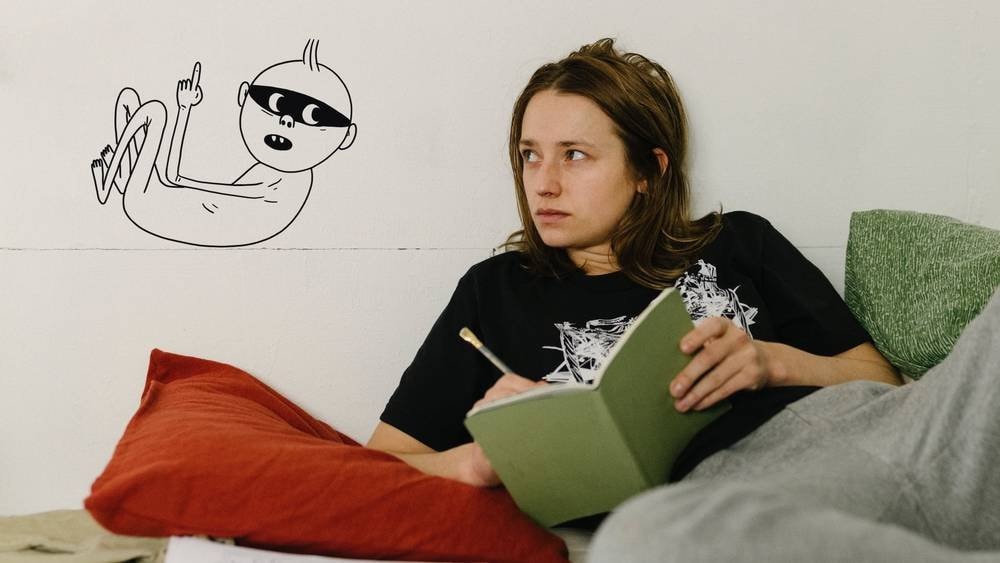

into my hair dark brown rebozo glitters red silk in the sun my protector carry the young to their destiny weave stories into their hair about their blood, their skin about the things they will never get to see cover their heads with the rebozo of your mother the one she claimed as her second skin help it find its way back to the soil where she knelt tending to the earth so weave weave stories into my hair my blood, my skin etch it into the backs of my eyelids let it warm me as the cloth of a thousand colors, a thousand lives silence envelops me i don’t hear so much as feel the smooth beating of your heart the sun peeks through the space in between the weave and i tug at a loose thread connecting you and me cover my head eyes closed my veil as the stories of those that have kept me company in solitude preserved by the stillness falls to pieces at my feet in lifeless puddles of night within the folds of the cloth smuggle pain across borders wrap this second skin tight tighter don’t let your blood find it’s way back into the soil my eyes, my skin, my blood you are not who i thought you were from hand woven stories to synthetic lies let it be my protector let it be my veil let it be mine porque el olvido is a dangerous thing so sit down beside me and weave your stories into my hair n.m. by Phil Segal The Mill Valley Film Festival recently wrapped. I was lucky enough to catch five screenings, four at BAMPFA, one (Ninjababy) online.

Memoria Apichatpong Weerasethakul has always been happy to let audiences’ eyes and ears wander around the frame at their leisure rather than controlling their attention (he likes minds wandering, too). Despite some worries I had about an “English language debut” featuring, at least compared to his previous work, a superstar, putting Tilda in the movie hasn’t changed anything: she’s just occasionally one of the things in the frame that you can choose to focus on, a useful tool compositionally because her body is a powerful set of lines. In the earliest days of film, shots would be composed to utilize lots of diagonals to create something visually dynamic in spite of a frequently stationary camera; frequently here Weerasethakul does the same, holding stationary shots that nevertheless keep your eyes in motion, and he has painter’s eye for arrangements of color and light as well. Even the shots that went on for minutes I felt like I hadn’t finished looking at and hearing. The purpose of shots is not to advance what little plot there is but to create visual and aural arrangements to be appreciated in the moment; if you can approach it in that way, it’s a generous, welcoming experience. Lingui, The Sacred Bonds Two sisters, long estranged, have a tense meeting in which one is unwilling to budge. Until, that is, the other sister mentions trouble with her husband, providing a catalyst for the two women to unite. This Chadian drama celebrates women watching out for each other in a world where men can’t be relied on or trusted and makes the case for the necessity of safe access to abortion. It’s well-performed, incredibly timely, and uplifting. What it isn’t is very cinematic, with veteran director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun sticking to the standard realist style of modern message pictures, but the lack of distinctive film style is ultimately inconsequential compared to what he does right with his screenplay and his handling of tone. The film doesn’t downplay the struggle its characters face or how serious the risks they take are, but focuses on resilience and resistance, resulting in an ultimately energizing film rather than the noble downer you’re likely expecting from a film about abortion rights. Ninjababy Rakel, the heroine of Ninjababy, also wants an abortion but finds out she’s much farther along in her pregnancy than she realized despite showing no signs. She frustratedly declares that it must have been some kind of “ninjababy” in order to sneak up on her like that. An aspiring graphic novelist who’s constantly scribbling on the scenes around her in her mind (one of the inventive blendings of animation and live action throughout the film), it’s not long before she’s drawn the “ninjababy,” which immediately takes on a life of its own, popping up on papers and walls to argue and make demands, much to her chagrin. Yngvild Sve Flikke’s film is an unusually raunchy, strange, and frequently hilarious look at an unwanted pregnancy, a film with characters called things like “Dick Jesus,” a sequence featuring stop-motion sperm, and one of the more charmingly irresponsible mothers-to-be in film history. In the end things get more heartwarming and sincere, and that’s all handled well, but it’s the crude and comical (in multiple senses) journey to get there that’s the original and exciting part Bergman Island Mia Hansen-Løve’s latest is another confirmation of her impeccable skill as a filmmaker. Her films are some of the most fluid being made right now; every scene ends a little before you expect it to, hard cutting the moment someone finishes talking or comes to rest, so that there’s a ceaseless momentum to her films, and the frames always include exactly what is necessary to convey information about her characters and no more for only as long as it takes to absorb that information, so that your attention is continuously stimulated and carefully controlled. It’s truly auteurism in that it creates the same effect as literary narration, the world described with a distinct voice and point of view, through visuals and cutting. An identifiable “prose” style runs through her work, the filmic equivalent of the brisk, well-constructed sentences of a Hemingway or Didion. I was slightly disappointed by what she wrote this time out, with the qualification that I’ve never had any attachment to Bergman, although as the film goes on and adds new layers it becomes more interesting. If her previous films like Things to Come hadn’t set the bar so high I would probably be more impressed by this one, which is quite good but no Things to Come. Graded against anyone other than herself, though, it’s an unqualified recommendation. Drive My Car Drive My Car is three hours long, with a narrative that unfolds in a relaxed, winding manner, and yet I never felt my attention flag or that anything Ryusuke Hamaguchi opted to show wasn’t adding to the film. A lot happens in the lives of the characters we meet over the course of the film without it ever quite feeling like a plot. The interest is not so much in seeing how one thing will lead to another; instead, it’s just what these characters will do in each situation they encounter, where their conversations will take them, because they come across as rounded people full of contradictory impulses and motives that aren’t always clear, even to themselves. Adapted (apparently loosely) from a Haruki Murakami story, the film deals with the world of theatre, large parts revolving around rehearsals for a multilingual staging of Uncle Vanya. It’s in part a film about the power of art to bring people together, to help people process things that happen to them, and to reach across time and space to speak to us. Mainly, though, it’s a film about people, the steady accumulation of detail over the three hour runtime reminding us that there are few things richer and more mysterious than what goes on within and between human beings. by Phil Segal Ahead of the CineSpin event on November 12th when they’ll providing an original live score to Kote Mikaberidze’s Russian silent film My Grandmother, I had the chance to talk with musicians and composers Gabriel Sarnoff and Miles Tuncel. You can check out music by Gabe and Miles here (Miles appears on track 2, “Satisfaction”). Our talk covered improvised music in the Zoom era, what makes accompanying a film particularly exciting, and what they hope people will get from the CineSpin experience.

BAMPFA SC: Why don’t we start with an introduction and go over what led you here? Miles Tuncel: Hi, I’m Miles, I play primarily saxophones. I’ve been playing saxophones for ten plus years now, since I was in middle school, and I met Gabe in an ensemble at Berkeley-- Ben Goldberg’s class, who’s a big hero and teacher of ours. We sort of took off from that, improvising and composing together, playing a lot of different genres of music, a lot of different settings. We also played in Myra Melford’s group on campus, which is an improvisational based music class. I’d say those two classes and those two people have been huge inspirations for us in terms of how we approach composing and improvisation and playing with each other. Gabriel Sarnoff: To go off that, I came at music starting in ninth grade. I started playing guitar, played in a pretty “hard rock” band throughout high school with some buddies, and then towards the end of high school got into playing upright bass. I was the electric bassist of this band, and then wanted to play upright base, joined the school’s small orchestra (I went to a tiny school), and that’s what got me into reading music and classical music. Then I came to Cal, studied music as one of my double majors, and met Miles in that class in our junior year, and from there kinda found myself in this corner of the music department at Berkeley, and just generally music in the Bay Area, of improvised music primarily. Ben Goldberg and Myra Melford are pretty well known in that area of music, very respected, and they’ve become mentors for us. We’re following in their footsteps but doing our own thing. We approach music I think a bit more from— at least I do, and I think Miles as well— Miles has more of a jazz background whereas I have more of a rock/folk background, but we both appreciate that other style of music, and so we come together and create a synthesis of the two and pair it with improvised music to get something really special that we think will go well with the silent film. We’re excited for this opportunity because it’s super-unique, to say the least. BSC: How did you end up getting this opportunity to do CineSpin? GS: I think I got an email. I’ve known about this event, I went to it two or three years ago, and I was like, “Wow, I really wanna do this! This is so cool.” So I saw the email and we sent in a song that we had made for a new jazz ensemble. We actually sent in a song that we made over Zoom, because we were doing everything over Zoom during COVID. BSC: Were you improving over Zoom? MT: Yeah, it was a big part of our lives for a year or so. It was a really different experience trying to play music over Zoom. It’s a difficult prospect but it led to some interesting results. We would never really have thought about playing music or composing in the ways we did before everything happened. GS: For example, the song we sent in, we were playing along with a friend of ours, Evan, who was in this ensemble with us. He was playing bass clarinet I believe, [Miles] was playing saxophone, I was playing guitar, all over Zoom. I think it was completely free improvisation, there might have been some melodic structure that we were basing it on, but Evan was using a pedal that pitch shifted what he was playing, and that wasn’t coming across to us. He was hearing himself play completely different than we were hearing him play, and it led to a crazy sound that wouldn’t have been possible had we been playing together live without that filter between us of Zoom. So the Zoom/COVID era opened up a lot of doors for musicians doing free improv music. I think for musicians working in more rigid forms where everything has to stay in time, they were probably kind of screwed, but since we’re not based in a time signature or tempo, things are looser in free improv, it led to interesting results. We realized that you don’t have to hear everything that everyone’s playing at once to create something beautiful. You only hearing what one person in the ensemble is playing, and that person only hearing what a different person is playing, it creates really interesting results. BSC: I’m interested in your approach to working with film because Gabe, I actually had the chance to view a talk you gave (viewable here) on representational aspects of music and how that affects composition. Could you explain a bit about that, and maybe that can lead us into how you worked with this film? GS: Yeah, so my theories on composing and music are pretty abstract and mainly exist in my head, so they’re probably not too logical, but I guess the basic idea of how I see music, how I hear music, is as a narrative form. A good example is when you’re listening to classical music, like an orchestra playing, there’s usually a lot of people playing but only a few melodic lines going on at a time, because if you do more than four or five at a time no one’s gonna know what’s going on. I hear each of those voices as kind of characters in a story. If I’m listening to a piece of music and it’s guitar for a while, and then the bass comes in, it’s analogous to when you’re watching a movie and following a one person for a while, and then a new character walks in and joins the storyline. I think it’s a very valuable perspective, because when you’re working with music it’s very abstract. People can get caught up with doing too much and adding too many elements just because you can, especially in our digital age when you’re working on computers and have the option to add hundreds of tracks on top of each other. Some people do that, a good example being Jacob Collier, who’s a composer and musician that’s pretty well known. He’s big on that, putting three hundred vocals on one song, all on top of each other. That’s its own thing. That’s not my approach. My approach is that if you’re writing a story, you’re not going to have three hundred characters, or no one will know what’s going on. I prefer music with fewer elements, with each element more developed. That being said, the movie My Grandmother, we just watched it for the first time, and it’s a very hectic movie [laughs]. There’s a lot of… It’s more of that Jacob Collier side of things with a million different things happening. In this project, for us, one thing I was thinking about when we were watching the movie, is that we can’t match that with two people playing live. We’ll have to create something that can have a contrast to the movie. If we were doing a film score where we recorded everything and were able to compose meticulously, that would be one thing, but live we won’t be able to match the superfast cutting and rapid changes of events. For example, there’s a scene of a guy sliding down a railing on a staircase, it’s a recurring thing, and I’d love to go [imitating slide whistle] to mirror him, but I think we’re going to try and exist in a separate dimension, where we’re not necessarily mirroring everything that’s going on but the instead aiming for the contrast of the music to give meaning to the movie and the movie to give meaning to the music. That was a lot [laughing]. BSC: Miles, do you share Gabe’s theories of music or do you take a different approach to thinking about it? MT: I’d say that reflected my sort of way of approaching music pretty well in terms of storytelling and character. I think the music to me that is the most interesting, and I guess this expands to all art, is where it’s not something perfect, where you can hear the artist struggling to achieve something. It’s not perfect, but it’s what they have, and they’re putting all they have into it. I think in terms of scoring things, that’s where our experience in improvised music pairs well with scoring a movie, because in improvised music you can have so many kinds of interactions between people: between the performers, a conductor, the audience, so there’s a great fit between interacting with a movie and improvised music performers. BSC: How does that play out for you? The film is something rigid, locked in, it’ll be the same every time. Is it freeing for you to improvise against because you always have that baseline, locked in thing to return to no matter how far out you go, or do you find that restrictive, that you can’t go out as far? MT: I think that can be freeing, and that’s something important in music, to have some kind of structure that the listener can lock onto and say, “Oh, I know what’s going on here.” So I think it’s a good baseline to build off. And there’s all kinds of baselines in music that you can build off and take form from, so I think this is just another one of those structures to add music to. GS: If I can add, I’m taking one on one lessons with the clarinetist Ben Goldberg we mentioned earlier, who teaches improvised music at Cal, and in these one on one lessons we’re basically working on melodic improvisation over chord changes. So the music we’ve done with Ben and Myra in the past, and what we’re going to do for this movie, for the most part, is the opposite of what traditional jazz is. There, you have a sheet of chords, and for four bars it’s a C Major, and then it’s a G, and then yadda yadda yadda. In our kind of free jazz improvised music, we’re only following our ear with no predetermined chord structures, which leads to a huge realm of possibilities. But, in these lessons I’m doing the opposite, I’m working on going through these chord changes and creating a mental map that you can use to anchor what you’re playing. What I think is cool about this movie project is that the movie takes on the same role as the chord sheet in a jazz standard, and we can use that to anchor our playing. In the course of the next few weeks we’re really just going to learn this movie as if it were chord changes. It’s going to be impossible to memorize every single action in the movie, but generally we’ll know, “Oh, this is going to happen next.” If we have that really under our fingertips so we don’t have to think about it, that’s when it frees you up while you’re playing. The biggest thing is that we’re improvising and we won’t be talking, so we have to have something— usually it’s our ear— keeping us together. If we both know what’s coming next in the movie, though, that’s going to create wild possibilities. We’ll both know a crazy scene is coming up, and that will influence our playing, and so we’ll… I don’t know! I don’t know what’s gonna happen, but I think it’s so unique. So my answer is that I don’t think it’s limiting. Quite the contrary. BSC: If I could bring us back a bit to your talk, you mention there that normally the audience doesn’t have direct access to the images or feelings the composer means the music to represent. Here, we in the audience are going to be looking at the image you’re trying to represent at the same time you’re looking at it and trying to represent it. What effects do you think this will have, will it be more challenging for you, does it take away something by limiting possible interpretations? GS: I was thinking about this. We watched it last night, actually, and we were just brainstorming. I was thinking about what I mentioned earlier, that we can’t match everything in the movie as two people playing live, it has to be a freer connection between the two, but since the audience will be seeing the movie and us simultaneously they’ll create connections we weren’t even imagining. That’s my plan. MT: Yeah. GS: I think the audience’s brains will play a big role in creating the meaning behind the music, in an abstract sense. BSC: So everyone will get their own experience of it. It’ll be totally open in that way. GS: Yeah. BSC: So to prepare for this, is there any music or anything else you’ve been drawing on? Have you been listening to film scores, or jazz/improv, or looking for inspiration anywhere in particular? MT: Yeah, I think we’re always playing what we’re listening to. I’ve been listening to a lot of Wayne Shorter recently, he’s one of my favorite saxophone players. There’s this record that’s fairly recent, in the last ten years, called Without a Net, that I think is very good at representing a story. I think that record is some of the saxophone playing that I’m always striving to match in terms of storytelling and being a character and having your own voice. GS: Definitely we should be listening to more film scores. To speak for you [points at Miles], he’s been listening to a lot of… I’m not sure where it’s from, but this flute music. MT: Oh yeah, it’ s a Turkish ney, it’s a kind of flute. GS: Miles influences me a lot because he shows me a lot of world music with instruments I’ve never heard of. A lot of times in the US, and Western popular music, songs are pretty rigid and three to four minutes, so it’s nice to hear something a bit more fluid. Film scores are like that as well. A film score is probably where people living here, like students at Berkeley for example, get most of their long fluid music. It reaches them through movies. I definitely think I’m inspired by the music Miles has shown me, as well as finding a way to merge some of the other work I’m doing right now. I’m creating folk songs, or like Bob Dylan-y singer-songwriter-y songs, wondering if there’s a way to bring stuff like that, maybe some singing, to the film score table, but we’re still parsing together everything. BSC: Do you think film scoring is something you’ll want to explore more after this? GS: Definitely. As a musician— I just graduated Cal and now I’m trying to pursue music full time— a career in film scoring is one of the more stable careers for a musician to have, if you can make it in that area, so that’s really appealing to me. I think as an artform, I still haven’t explored it enough. That’s why I’m really excited for this project. I see this as an artform that no one’s really doing, pairing this kind of improvised music with silent films. If it goes well— I think it’ll go well— I’d like to do more of that specifically moreso than just film scoring in the traditional sense. MT: Agreed. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|