|

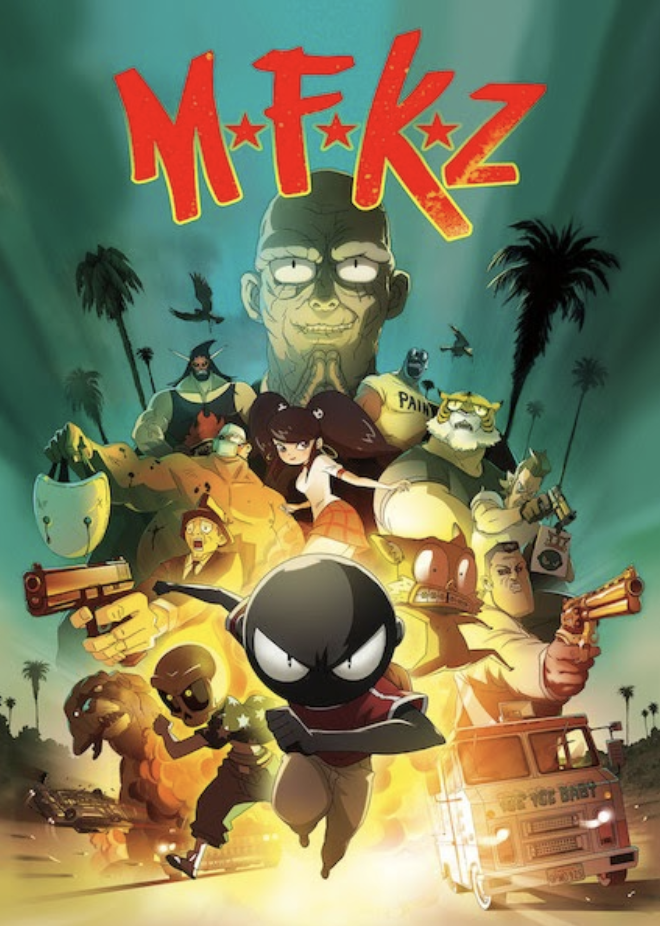

by Saprina Howard MFKZ, short for motherfuckers, is a tasteless anime film written, produced, and directed by a slate of non-American men. It follows the life of an African American alien character named Angelino, who is “ just one of thousands of deadbeats living in Dark Meat City. ” (IMBD Synopsis) Aside from the obvious ode to Los Angeles in the protagonist’s first name, this synopsis is LOADED with coded racial language like “deadbeats” and “Dark Meat City.” The film may be fantasy, but it is clearly a portrayal of non-Hollywood Los Angeles. One may argue that to critique a “fantasy” film on the terms of real life is unreasonable. Oftentimes where race is present in anime, a colorblind audience is quick to discredit any harmful meaning in the overtly offensive depiction of African American culture. However, to truly dissect a film we should put it into context-- into its place and time. Whenever a hideously drawn Black character makes their way onto the screen, Black viewers cringe. Too many times Black anime consumers must quell a sickening feeling as they watch caricatures perform violent, loud, or inhuman behaviors. Many of the Black characters in this film are racial caricatures lifted straight out of Jim Crow era Minstrel shows! They remarkably resemble a mix between a Pickaninny and a Buck. Even in anime, known for its limitless potential and imagination, Black people are not imagined outside of the confines of reality’s burdensome stereotypes. The directors of this film and their internalized anti-Black ideas are to blame. The professional team behind the creation of this film are from France and Japan; nations that refuse to acknowledge their Black population. Japan denies Japanese identity to half-Black citizens and France suffers so badly from colorblindness that it’s illegal to consider race! Anti-Blackness is programmed into the citizens of both of these societies. With small Black communities unable to represent themselves in French and Japanese societies, both countries remain largely persuaded by negative portrayals of Blackness in the media. If art is a reflection of one’s values, then this film reeks of the creators’ anti-Black sentiments. It is a highlight reel of every racist thing they have ever thought about Black people. Let us focus on the depiction of one neighborhood from the film: In the film a neighborhood named Palm Hill seems to be an interpretation of the Palmwood cul-de-sac and Baldwin Hills, both historically Black communities. MFKZ embraces the trope that Palmwood is violent, filthy, and that gun violence, drugs, and joblessness run rampant. In the movie the neighborhood is so chaotic that even people’s homes are falling apart. These myths about Blackness and Black neighborhoods have been popular since the Transatlantic Slave Trade. After emancipation in 1863, codes and vagrancy laws criminalized Black people who were unable to find work and justified terrorizing free black folk for demonstrating their human right to freedom. Since then, vagrancy myths that conjure stereotypes of laziness, deviance, and aggression were popularized by the western world’s media and have remained the main examples of African American culture for some homogenous societies to this day. The film's atrocious depiction of Black inner city life misses the mark, as well as an opportunity to creatively engage an anime version of the beauty that already exists in Baldwin Hills and the Palmwood neighborhood. Instead, the hideous Palmhill neighborhood in MFKZ serves as a cesspool of racial tropes and plotless violence. Japanese anime creators endlessly reimagine medieval Europe. With eurocentricity and whiteness so romanticized as part of anime’s visual appeal, this is evidence that anime is not colorblind. Race and reality are augmented within anime worlds and if white culture earns reverence by anime creators, then they can certainly find it in themselves to revere Black culture too.

Black people are famously consumers and lovers of Japanese pop culture who deserve more respect than anime currently alots its Black audience. When anime creators finally appreciate the richness and nuance of Black culture instead of demonizing or bastardizing Blackness, maybe Black audiences can breathe a sigh of relief instead of holding their breath for not knowing which racist portrayal comes next.

95 Comments

by Truly Edison image via mentalfloss Remember all those Daniel Craig Bond movies? No Time To Die is apparently still coming out...eventually. Evidently, not on any streaming platforms, according to the most recent news from producers. I myself am violently neutral on this newest Bond reboot (if maybe still a little annoyed from having to hear “Skyfall” on the radio ten times a day back in 2012). I could never put my finger on exactly why I didn’t find them particularly compelling; something about them just didn’t click for me, some unidentifiable but obvious element. But recently I came across an article from earlier this year that started putting the picture together for me just a little bit more—it proposed the idea that this newest reboot of the series struggles because it finds itself living in the shadow of parodies and other campy iterations of its genre. Namely, the Austin Powers films. Now, for the sake of putting any and all biases on the table from the get-go, I am an AVID fan of Austin Powers. The first film is easily one of my favorite movies of all time, and that’s movies, not comedies. My high school girlfriend almost broke up with me junior year because I got so obsessed that I started reflexively talking...Like That (groovy, baby ☹️). I read Surrey’s article first because of the selfish fan Schadenfreude that came from the idea that these stupid movies I love were tangibly screwing up a multi-billion-dollar cinematic universe (as well as the obvious dirty joke in Craig’s lament that ‘Austin Powers fucked James Bond’). What I got out of it was a perspective on the whole phenomenon I had never considered before. These modern Bond movies have undertaken an uphill battle: the quest of becoming the ‘serious’ Bond films. They wanted to create a Bond who was nuanced, who had more weight to him than previous incarnations of the globetrotting, womanizing spy. They feared letting the lingering silliness of the character—of the concept—seep too much into their new films. And they definitely didn’t want to get too close to the cultural legacy of Austin Powers. But where I personally think Surrey struggles a little is in his lukewarm expression of just how integral this campy approach is to Bond films—to spy films in general, to be honest. He’s willing to admit that camp might have been “occasionally the intention”, skirting around it in reference to the older films like it’s a bad word or something. I want to take it a step further. In my opinion, these movies HAVE to be campy to work at all; trying to overcome the inherent ridiculousness of the premise is a burden that not only can’t really be shed but shouldn’t be. Like, I can’t be the only person who finds something about all those classic Bond films kind of hilarious, right? I can’t even pinpoint exactly one thing; perhaps some part of it is looking at them in retrospect. After all, in a post-Bond world, they can have a tendency to run like parodies of themselves. Those over-the-top opening credits, all those tropes and cliches we know and love presented as-is in their original context with no self-consciousness or pretense of satire...poorly aged as they are, there’s an undeniable sort of charm there. Even if we go off the assumption Surrey makes that the humor here is incidental, you can’t name a character Dr. Goodhead on accident. I mean for fuck’s sake, one of those films is called Octopussy! That’s the title of a real Bond movie! It’s not a porn parody! Spy movies in the style of James Bond are dumb as hell, and I say this as the most sincere of compliments. If you’re still not convinced, just try and listen to the opening theme for 1974’s The Man With The Golden Gun with a straight face. And taking something like Austin Powers into account, parody is the most natural cultural response to films like these. There’s just so much perfect raw material! Nothing new even really has to be added—all Austin Powers does is crank existing tropes up to eleven and put them in a ‘real world’ to highlight the absurdity. Honestly, I feel like with less time travel and genre consciousness Austin Powers could have run as a fairly-straight series of spy films (and 16 year old me probably would have been just as obsessed with it). Perhaps the easiest way to illustrate what I’m trying to get at here is to pull an example from a more immediately obvious failure: the mid 2010s attempts to revive Superman, particularly 2016’s catastrophic Batman vs. Superman. If you're making a theoretical ‘gritty’, ‘updated’ Superman movie, you’re going to run into one major problem: Superman is, innately, a guy in a blue spandex suit who shoots lasers out of his eyes and dies if he touches a certain kind of rock. And that’s hilarious! If you lean too much into preserving these inherent qualities of Superman, you’ll wreck the intended tone of your film—but if you stay away from them, you won’t end up with a Superman movie at all, just the awkward and over-compensating shell of one. Spy movies, particularly Bond movies, work the same way to me. It’s the parts that are cheesy and dumb that are essential. So in these recent Bond movies, you end up with this almost Freudian return of the repressed as they work so, so hard to hold back the nature of their own existence. It’s how you get cultural oddities like Casino Royale (2006)’s infamous cock-and-ball torture scene (click at your own risk!). As the first of the modern, newly ‘serious’ Bond films, it had the most daunting challenge to overcome—the need to completely define out of the genre the very things that made it. The scene is off-puttingly, and yet hilariously brutal and unnecessary. You can just feel some poor writers going See? See? Bond movies are tough and gritty now. Please don’t laugh at us. Granted, some of that humor comes from the consciously written dialogue, but a hefty portion of it is completely situational. You want to laugh not just at Bond’s shrewd wise cracks but at the whole thing, while at the same time kind of knowing you aren’t supposed to. The need to differentiate inevitably cycles back into absurdity. The harder you work to hold that essential nature of the Bond movie back, the harder it’ll pop up to bite you in the ass for trying to ditch it. It’s inescapable. And why should we try to escape it? Why should we be afraid of a little camp now and again? It’s not a crime to make a stupid movie. If anything, we could use more stupid movies. I get so tired out by the same old cement-gray oh-so-serious vibe of (cue bitter old man voice) Movies Today™. Sure, movies today are ‘good’—but are they fun? That’s a bit of a trick question there; in my opinion, at least, a movie that’s fun is good, even if the movie is bad. And I’d rather have a fun ‘bad’ movie than a boring ‘good’ movie any day of the week. There’s this poor guy in the comments section of that Man With The Golden Gun clip who says “I have no idea why people think this movie is ridiculous. It's one of my favorites.” Take it from your local Austin Powers enthusiast: there’s no reason those things can’t both be true. In the case of Bond films, maybe they even both should be true. by Khaled Alqahtani It’s the 10th week of the semester, and I’m thrilled to announce that I haven’t had a breakdown (yet). Although I’ve been on the verge of many, taking the semester back home and being closer to everything I’m familiar and intimate with has managed to bring me comfort every single time. And I’ve been recently just observing and documenting them in an attempt to immortalize them, or at least fully appreciate and celebrate them as I'm constantly haunted by the idea of losing them.

Expressions of intimacy, both physical and verbal, have always been explicit around me: kisses, hugs, and all. But it took me too long to recognize and decode the implicit ones. My inability to recognize them was a result of me speaking only my love language, which I used with others without considering if it was enough for them or not. I didn't even slightly try to understand it because I thought my language was the only way to do it. I'm currently learning how to speak their languages and understand their definitions of love and intimacy, and how they like and feel comfortable to express them. My mother asks me every evening to share a cup of mint-tea with her. My dad touches my head and whispers a prayer every time he passes by me. My siblings share their favorite Sheeren's songs with me. I can list at least one sign every person I know uses to show their closeness to me and other people around them. Being homesick while in Berkeley was my only personality trait at one point: "home" and everything this term entailed was everything I talked about and yearned for. And it was these small moments that I always longed for while being away, and they're the ones that always kept making go back when I knew that home didn't always love me back. I'm facing the same issue of longing for people and Berkeley right now while I'm back home. Yet I'm instead trying to just appreciate them and bask in what I have now instead of constantly yearning for what I don't have between my hands. by Katherine Schloss First of all, Lulu Wang- the director of The Farewell- is life partners with Barry Jenkins (who directed Moonlight) and I just think that that’s so special. Also, this is a PSA: Kanopy is amazing and I wish that I’d known about the free access that Berkeley students have to so many amazingly artsy and touching films earlier on in my college career!!

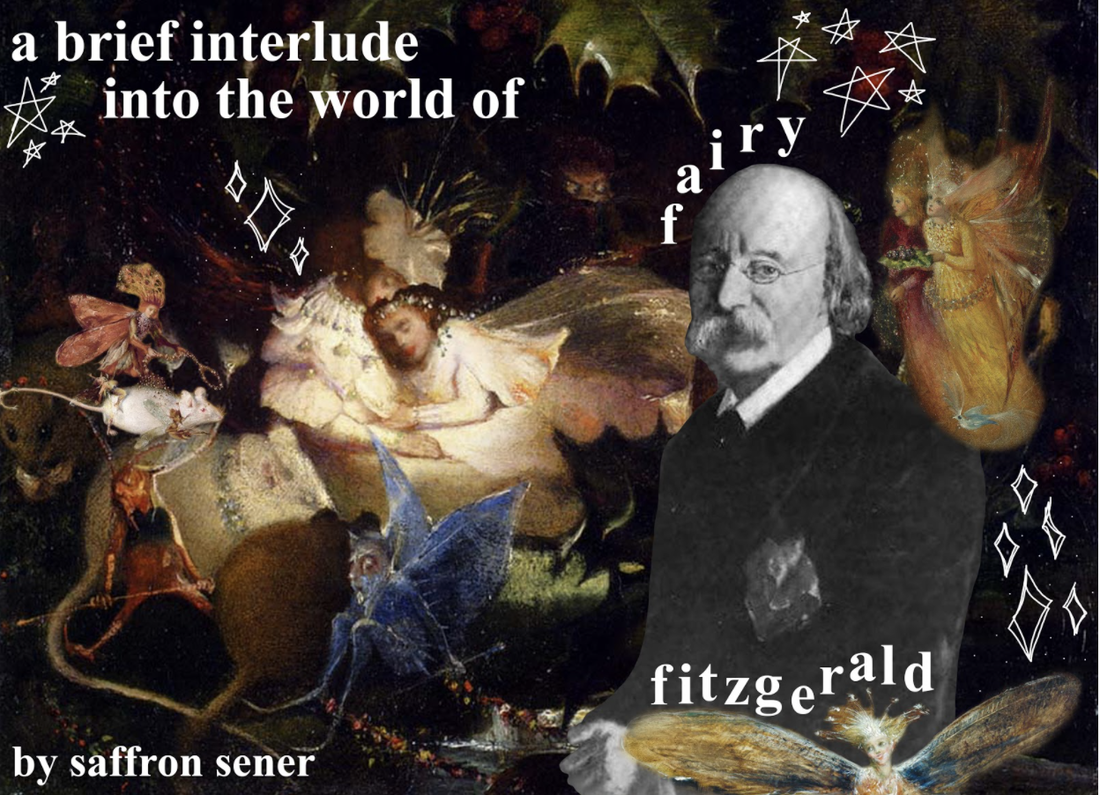

I watched The Farewell (on Kanopy) for the first time a few weeks ago. Ingesting a film that is inherently centered around death seemed like an odd choice at the time- especially because my viewings up to that date had been about the escapism that comes with rewatching comedies that are dear to me, such as New Girl (a show that truly never disappoints and makes me feel fine about my own quirks), or about diving headfirst into trashy reality television dating shows. After watching The Farewell, I felt reawakened and safe in caring about the drama that is whipped up in the squeaky halls of Grey’s Anatomy- despite the fact that the show has a death:episode ratio of about 1:1 (and that’s ignoring the episodes with the big, all-encompassing traumatic events). My time during this god-awful pandemic has been largely defined by questioning how I view big life events as they are slowly reduced to their barest bones. Holidays become an excuse to dress up, and birthdays an excuse to stuff my face with cake. In the film, Billi (Awkwafina) travels from New York back home to Changchun in northern China to attend her cousin’s wedding- which is a ruse to get the whole family together before they lose their beloved matriarch. Her grandmother is dying, and she can’t tell her. As the film explains, this is not looked down upon in Chinese culture, where the family members are seen as being responsible for taking on the burden of death. The supposedly joyous wedding ceremony takes on a whole new meaning and purpose, becoming cloaked in death. Death is treated as a taboo subject in the film, and yet it’s all that any of the characters can think about. Death has really been ever-present lately. The decaying of democracy. The death of plans. The death of certainty. And, more seriously, the threat of real, bodily death as we all face the virus that none of us can truly stop thinking about. Billi is a young artistically-minded gal who is struggling to find herself in New York- a mindset that I’m currently inhabiting despite my noted physical absence from that city that I want to eventually find myself in. She finds herself confronted with her own individualistic existence in the face of the impending death of her grandmother. I felt Billi’s crisis. I understood her willingness to pick up her life and avoid it all by moving to another country, far away from all of her own problems and ready to care for someone else. I know that I’d do the same for my own grandma. But surprisingly, I felt that Lulu Wang wanted audiences to focus on the family dynamics at play rather than to zone in on Billi’s identity crisis. As I’ve found to be characteristic of A24 movies, The Farewell is beautifully staged with its soft colors- but I was surprised at just how mellow and subdued the film felt despite its exploration of complex topics such as what it really means to pursue the American dream, what it feels like to return home, and how to keep a lie for the good of someone you love. Billi learns that, when entangled in a family, there are some things that you can’t plan, some things that you need to let slip into the hands of others despite a desperate need to have some semblance of control over your own life. She navigates her own role in a family that feels so unlike her in both action and attitude, finding that her own identity will always be an amalgamation of what she knows herself to be and what her family sees in her. Without revealing too much, when Billi finally walked down the streets of New York and suddenly broke into dancing and screaming, it felt like an embodiment of what goes through my head as I put my airpods in and drown out the world. And I was here for it. All of it. by Saffron Sener If you ask, I will tell you that the focus of my studies in art history is Flemish art. That’s untrue, though, for two reasons: 1) in my time here at UC Berkeley, I have never been able to take a Flemish or Northern Renaissance art course, because, frankly, they aren’t available and 2) my real interest is in weird art. By weird, I mean monsters, little beasts, witches, mythical creatures, allegories, fairies, angels - but mapped onto our world, or early modern perceptions of our world. Think the Bruegels, Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymous Bosch, Francisco Goya, Fra Angelico, John Martin. I don’t necessarily need my art to move me to some great emotional conclusion; I want to be endlessly interested by its strange characters and unique perception of reality, by a glimpse into a world more magical than my own. But I’m not writing this to ruminate on my internal turmoil about my art history concentration. I’m here to talk to you about Fairy Fitzgerald. A 19th century English painter of fairies, dreams, flora, and fauna, John Anster Fitzgerald embodied a very Victorian fascination with magical otherworlds. He became known as “Fairy” Fitzgerald by his contemporaries for his loyalties to the creation of fairy scenes. Strange, elvish creatures fluttering beside miniature peoples dressed in acorns and flowers, commiserating with kittens and baby bats (A Cat Among Fairies), or maybe a rabbit (Rabbit Among the Fairies). Long limbed, sharp winged things scratched across the canvas, fluttering over ocean waves that tumble over each other onto a seaweedy beach (Sea Sprites). The Wounded Squirrel, John Anster Fitzgerald, likely 1860s Works like that above feel like an attempt by Fitzgerald to reckon with the rapid industrialization of his native United Kingdom and the destruction of its natural landscape. We’ve all likely learned of the peppered moth, whose quick evolution from a white and black mottled coloring to a wholly black coloration was due to the intense exponential increase in industrial smoke in 19th century England. This pollution was so severe that soot blanketed the English countryside, enveloping trees so thickly that only the darkest moths could be sufficiently camouflaged and survive. The tangible effects of unfettered, destructive industrialization were growing into themselves during Fitzgerald’s lifetime, and the natural world of this period was much more suffocated, unstable, and under threat than that of a century prior. The Wounded Squirrel depicts a far different human relationship with this world. Humanlike creatures (made more pure by their expansive, colorful insect wings, and humbled by their miniature size) heal an injured squirrel; there is no dominion of one over the other. The background of this piece extends into an untouched, idyllic meadow. There is no soot, no smoke - Fitzgerald utilizes mythical beings to imagine a reality much unlike his own in 1800s London. I attempted to learn about Fitzgerald’s upbringing or artistic background to better understand his great allegiance to the fairy genre. However, I found little information because there is little information to find; his biographers and the few art historical considerations I unearthed about him all agreed on his vague personal life. His birth date is unclear, sometime between 1819 and 1823. He is assumed to be a self-taught artist, but is known to have been exhibited in the Royal Academy of Arts in 1845, when he was likely in his mid-twenties. His father was a generally disliked poet by the name of William Thomas Fitzgerald whose poetry was rooted in English patriotism. Beyond that, though, his early life remains very shrouded. Fairy Hordes Attacking a Bat, John Anster Fitzgerald, 1860s Perhaps one of the more appealing aspects of Fitzgerald’s works to me, though, are their ominous undertones. Fitzgerald’s worlds appear beautiful, tender, enchanted. Yet, they are imperfect, almost sinister at times. Elegant fairy crowds watched over by fiendish things crouched in the canvas’ corner; they are whimsical, otherworldly scenes with an edge of danger creeping ever closer. His dream-related works feature impish creatures, hovering above sleeping subjects as they drift off into slumber (check out The Artist’s Dream for an example). Many tie his works to drugs like opium, a Victorian favorite, and the precariousness of psychedelic trips. Teetering between perfect wonderland and magical ruin, his scenes feign eccentric perfection. Yet, they are delicate fantasies; yes, in Fairy Hordes Attacking a Bat, there is a legion of little fairy people with wonderful flowery outfits and shimmery, iridescent wings. But they’re actively attacking a bat with broken twigs, forcefully pushing the wide-armed animal deeper into the background. What does this mean for Fitzgerald’s world? There is violent conflict - war, even. These scenes are no utopia. Fitzgerald melds the beautified ideal of a fairy - this half-human, half-butterfly thing - with Gothic, dark themes of his surrounding 19th century, of reconciling with the reality of nature being choked out by the grip of industrialization. He is very much a part of a somewhat disillusioned, fanciful movement; think Peter Pan (1902/04), by James Matthew Barrie, or Alice in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll. Whimsical, fantastical, but underpinned by a sense of deep instability and malevolence. Dripping with drug-induced, entranced imagery, tiptoeing between a sensational reality and hellish nightmare. A world that seems extraordinary and its dark, absurd reflection. In my opinion, one of his more captivating pieces is Fairies in a Bird’s Nest. Encapsulating that ever-present tension between the seemingly ideal fairy lifestyle and omnipresent threat of imps and devils, this painting calls upon Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights with its characterization of white, flowery people set against a populated, almost grotesque woodland scene. The body crawling into an eggshell at the bottom middle is a direct citation of the middle panel of Bosch’s triptych, where a crowd of bodies clamber out from a pool of water and into an eggshell. Light shines upon the head of the forwardmost woman in the nest, bathing her and her compatriots in a heavenly luminescence. The creatures encroach on this blissful twig shelter, crawling forward from edges of darkness - as if repelled by the radiance of these women and the flowers that lay across their bodies and nest, they do not enter. Fairies in a Bird’s Nest, John Anster Fitzgerald, 1860 I find, too, that there is a certain ability to map queerness upon this work; the closeness and tenderness of this moment, of these three women sheltering from the devils and imps that abound beyond the limits of their twig nest, feels particularly queer. Maybe I’m projecting my own queer desires (of living in a bird’s nest with my partner, not so much the devils surrounding us), but I do really struggle to believe these little fairy ladies drape themselves across each other and that twig shelter platonically. That’s so much more boring to me than if they were lovers, waiting out the night and the devils that reside within it. If I may really lean into a queer reading of this work - perhaps the devils and imps represent the hate-filled, monstrous perception of “sin” regarding homosexual love, and the soft, safe nest embodies a sort of queer refuge. I have no reason or evidence to believe that this is what Fitzgerald intended. I also understand that he was a man, so tracing a woman-centric queer love narrative onto his work is not particularly realistic. Does it really matter, though? This painting is meaningful in that way for me. Maybe I’m making Fairy Fitzgerald turn over in his grave. But, fairies, sprites, and their magical realm holds so much queer possiblity for me. My housemates and I all agree that Pixie Hollow Online was a communal gay root for us. Fairies in a Bird’s Nest just takes me further down that rabbit hole.*

* Oh, and it has an absolutely amazing twig frame - original to the 19th century. I swoon. by Sam Kurtz I don’t know what it is, but lately my social media explore pages have been showing me aesthetically pleasing screenshots of the movie Showgirls, a 25 year old movie that has been described as a “cheap porn film”. “Why is this movie that is 5 years my senior suddenly filling up my timeline?” was the question I was asking myself when a Youtube video relating to Showgirls came onto my recommended page. It was a great video by Broey Deschanel entitled “The Showgirls Redemption,” and I highly recommend it. One important thing this video did for me was it brought up the point of whether Showgirls was camp or not.

Now, deciding whether or not something is camp is a slippery slope because camp isn’t exactly definable. However, it generally falls into two categories: deliberate or naive. Deliberate camp is what it sounds like, a purposeful wink to the audience about how over the top and flashy what they're about to see is, and naive being an unintentional contribution to the oeuvre of camp. While there is definitely an argument that Showgirls is camp or satire of the harsh world of show business that chews girls up and spits them out, I just think it's a really bad movie. Now to be fair, I am not a film person by any means. I don’t know film terms or anything like that, but what I do know is when a movie is so bad it makes my skin crawl or time slow down, and that's exactly what this movie did. I have a lot of problems with this movie, both with the movie itself and with some elements surrounding the movie as well, so let's just dive into my hate piece against the trainwreck that is the movie Showgirls. One of my biggest problems with this movie is the way they used people of color solely to progress the white lead actress’ plot line. There were only two black people who had more than 10 lines, and they were both treated poorly or portrayed like an asshole. There was a temporary love interest, James, and Nomi’s best friend, Molly. While Nomi is a stripper, James calls her a hooker multiple times and is honestly just a dick to her. His main purpose was to try and teach Nomi how to “really dance”. But instead he awkwardly fingers Nomi to see if she's on her period, and then goes and gets the new girl at the strip club pregnant. The only other actor of color is Molly, a costume designer at a show in Vegas who is also in school for fashion, is flatly portrayed as the doting friend until Nomi pushes the lead girl down the stairs to take the spot for herself. Molly is very upset, justly so, but then Nomi tries to convince her to go to a party where her celebrity crush will be. Molly decides to go but is then beaten and raped by her celebrity crush and his goonies. While she is in the hospital, Nomi straight up abandons her and leaves Las Vegas without telling Molly. So both of the only people of color with lines are used solely for the progression of Nomi’s plotline and are treated with unnecessary violence and hate. Also there's a white girl with box braids and that just doesn’t sit well with me either. The next problem I have with Showgirls is the very unhealthy queer relationship that it depicts. In the beginning of the movie, Nomi goes to visit Molly at work as the costume designer for the dance show at the Stardust Hotel. That's where she meets the illustrious Cristal, the star of the Stardust dance show. While Molly is working on a piece for Cristal she introduces Nomi, where she informs Cristal that Nomi is also a dancer. When Cristal asks where she dances and Nomi replies The Cheetah, a seedy strip club, Cristal tells her she's not a dancer, thus starting their weird, toxic relationship. Cristal and her boyfriend Zack go to the Cheetah and then asks Nomi to do a private dance for both of them, which is essentially done just to embarrass Nomi and show her completely naked and flopping around like a fish on top of Kyle MacLachlan with aggressive bangs. Nomi then does one of the weirdest tryouts for a dance position I’ve ever seen, and manages to get a part at the Stardust, despite throwing two tantrums. Once Nomi starts working at the Stardust, Cristal takes every opportunity she can to embarrass or undermine Nomi, unless she's flirting with her or saying some of the most uncomfortable lines I’ve ever heard in a movie about doggy chow or boobs. In the end, Nomi pushes Cristal down the stairs to take her lead part, and before Nomi abandons her recently abused bestfriend, they share a bedridden kiss. Not only is this relationship extremely unhealthy, it's also just extremely uncomfortable. Whether it's their weird lines, awkward interactions, or the contrast of Cristal’s smugness and Nomi’s eagerness, this relationship, if you can even call it that, feels very uncomfortable and extremely forced. There are plenty of other problems within how this movie deals with how POC characters are treated or how gay relationships are depicted, but now I just want to rant for a hot minute about my opinions on this movie. There are so many aspects of this movie that A) just don’t make sense or B) make anyone watching it cringe to an ungodly level. Within the first 10 minutes, there are some of the most uncomfortable line delivery and acting choices I have ever witnessed. Whether it be something like Nomi slamming their fries on the table in front of the person who bought them for her or Nomi pulling a knife on someone like a child would in a cheap production of Rent, everything just feels so uncomfortable and so artificial. There have been arguments about how the over-the-top delivery of the lines in this movie is what makes it camp.But in my opinion, it's part of what makes it such a bad movie, but I don’t blame Elizabeth Berkeley (the woman who plays Nomi) for that. On another note, this movie also has a really weird focus on nipples, almost on the same level as a poorly written fan-fiction. Like don’t get me wrong, I love seeing boobs as much as the next bi person, but the amount in this movie almost feels exploitive, especially when you consider that this was Berkeley's first major role after she played a goody-two shoes on Saved By The Bell. While she was 23 and technically considered a fully consenting adult, the fact that she did full frontal nudity in her first major role just feels like she was taken advantage of in some way in her pursuit of stripping her title as the good girl. Another thing I don’t like concerning the treatment of Berkeley is the fact that the box office failure of Showgirls was blamed completely on Berkeley. After it flopped, she was dropped by her agent and ever since she's only been able to land small roles on TV shows. The most disappointing part is that her spastic acting was because the director told her to act that way, but yet it was Berkeleys career that suffered and not his. I mean don’t get me wrong, her overly energetic, borderline unhinged, acting and body motions was hard to suffer through, but if she was directed to act that way her head shouldn’t be the one on the chopping block. I have so many problems with this movie that writing full sentences about them would take up another 5 pages but I would like to share some of the highlights of the notes I took during this movie and give absolutely no context for them cause I think that just more fun:

In the end, it is still debatable whether this movie is camp or not, but in my eyes giving this movie the out of being camp completely overlooks the fact that it is a disjointed, nonsensical trainwreck that exploits people of color, slut shames sex workers, and has one of the worst scripts I’ve ever heard. I give it a 0/10 on the making sense scale and a 1/10 on the general movie scale. Overall, the only good thing to come out of this movie is the fact that it helped inspire the make-up for Euphoria, and that's about it. by Shine Lee I like the way that Vietnamese-American writer Ocean Vuong describes art — as public transportation. How whatever you create is always bound to go somewhere, to some station, and so even if you take the wrong line by accident you’ll still end up somewhere worth your time.

I hope I don’t look too pensive gazing out the window of the rickety time-stained NJ Transit Bus. I do wish I could be better at appreciating things right as they unfold in front of me — like the shreds of gum sticking to that young professional’s hand on the bus strap, or the pit-stained bearded middle-aged man dozing off on my shoulder as we’re all clumped together. It’s just that whenever I see those three words put together — “New” and “Jersey” and “Transit” — I often think about the people who’ve transited land and sea to New Jersey. Palisades Park, which is around the area that I spent my early childhood, is the only town in the United States with an Asian-majority (specifically Korean) population. It feels so close to South Korea that sometimes I even forget which country I’m in when I’m there, in spite of the fact that I spent nearly half my life in Seoul. Well maybe that just means that I’m directionally challenged. Regardless, growing up, the question of what this town represents didn’t cross my mind all too much; I think I had more important things to grapple with, like wondering why there wasn’t a rainbow Power Ranger or how in the world Pikachu’s thundershock could defeat a whole Onix. Yet later I began to notice just how unusual somewhere like Palisades Park was, that a group of people could construct a place for themselves that truly feels like their native home. Intercontinental transit. Maybe this is an easier way of saying the word “diaspora,” or the dispersion of any people from their homeland. “Diaspora” is a word that underlies Joseph Juhn’s documentary Jeronimo. Nearly eight million Koreans live outside of Korea (one of those eight million being me), which makes over a tenth of the entire population of both North and South Korea. Diaspora is one of those words that really doesn’t have any good synonyms. But that just means there’s something universal to be found in it, just like all the other best words in the English language: who, what and where. There is such a thing as a Korean diaspora, and there is even such a thing as a Korean diaspora in Cuba. Of course, never would I have even imagined there to be such a thing. In 1905, out of the 7,000 Koreans being moved to Hawaii to work at the sugarcane plantations for cheap labor, one ship left for the henequen plantations in Yucatán, Mexico. And the first ethnic Koreans to arrive in Cuba came from Yucatán in search of a better life. Jeronimo follows the life and history behind Jeronimo Lim Kim, a central figure in Korean-Cuban history. Jeronimo Lim Kim, or Lim Eun Jo, was the first Korean to attend university in Cuba and one of the leaders of the Cuban Revolution alongside Che Guevara. To be quite honest, I still can’t fully wrap my head around one of the earlier scenes in the documentary, which shows two strikingly juxtaposed photographs: one of Jeronimo surrounded by his Cuban comrades of the Communist Party, and the next of him wearing a traditional Korean hanbok and playing the Korean drums. In 1909 the contract for Korean immigrant workers in Mexico ended; but in just the following year, Japan took over Korea, meaning that the former Korean workers now became stateless. That four-letter word “home” had always been so close to that other four-letter word “hope,” but now with no homeland to return to, nobody really knew what either word meant anymore. Is home still a place? And hope the image of it? I’m inclined to answer no, that home can be anywhere and anyone and anything, that home is simply being able to feel safe, welcomed and included. But what if hope was contingent on the existence of a concrete, physical home? The very word “homeland” implies some kind of return or reunion. But what happens when you become so physically removed that the once-familiar soil, trees and mist become clouded in memory? One of the most memorable scenes from the documentary for me was when Jeronimo’s daughter points the director to a historical gathering site for the Korean community in Cuba, made to replicate how they lived back in Korea. No matter how abstract and unclear the image of one’s homeland — or returning to the homeland — might be, maybe there is some undeterrable desire in all of us to at least try to retain or come up with an idea of home anyway. This scene reminded me that it’s when parts of our identity are under the most pressure that our tethers to them become the most strong. It’s when we feel most distanced from something, someone, or someplace that we feel the most drawn to them. And ironically it’s often the people who are outside of the homeland — the Koreans outside of Korea — who are most protective and passionate about their Korean-ness, because it’s constantly being tested. This scene also reminded me of a passage from Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West, a novel that follows the intercontinental journey of two refugee migrants: “He was drawn to people from their country, both in the labor camp and online. The farther they moved from the city of their birth, through space and through time, the more he sought to strengthen his connection to it.” It amazes me that the idea of (a) home can possibly be even more powerful than the land of one’s home itself. I suppose it’s no wonder that there are places like Palisades Park, where a lot of the people are only able to speak Korean. Though in much different contexts, I think both Palisades Park and the Korean gathering site in Cuba point to an innate need to assure a completeness in our lives, through finding people with similar histories written on us. Our bodies are inscribed with maps, and like James Baldwin said, “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.” And so whether they realize it or not, those who have become separated from their origin are tracing their way back to where their histories came from whenever they assemble as a group. I used to always dread self-introductions — especially the classic “Where are you from?” question. I could never come up with a good answer for myself or for others, and sometimes I just ended up confusing people. I was born in Dallas, Texas, and grew up in Bergen County, New Jersey, and then in Seoul, South Korea. I went to high school in a tiny town in Connecticut, and now I go to college in Berkeley, California. I realize that the search for a home — to want to belong to and come from somewhere — often becomes a futile, unending journey. In Exit West, Mohsin Hamid mentions that “We are all migrants through time,” or that nowadays migrancy and “homelessness” is a common experience because every place in the world is always dramatically changing. But part of me wants a better answer than this. Because when I ask myself where I am from, I think I’m actually trying to answer a slightly different question for myself: “What is the history that you come from?” What stories of transit have my people passed down? I think this is a question that awaits every one of us. by Truly Edison horror-comedy legends Sam Raimi and the late George A. Romero - via Reddit

Sam Raimi has been one of my favorite directors since I was in high school, so I was really excited to finally sit down and watch The Evil Dead for the first time a couple of days ago. If this makes me sound like a poser, let me set the stage: when I was maybe seventeen years old and flirting with the idea of switching from pre-med to film, I stumbled across this interview he did on Youtube, probably related to some crappy WatchMojo video. In it, he was talking about The Evil Dead, which I’d heard of at the time, but never seen; my mom was a major horror buff in the 80s, so of course she’d talked about this great iconic horror comedy from when she was a teenager. I can’t actually find the link to this interview again, so hopefully I didn’t just spontaneously generate this somehow, but I remember it super clearly because Sam Raimi said that he really hadn’t intended for the first Evil Dead film to be funny at all. He was just as surprised to hear audiences laughing their heads off as were all of the Detroit citizens who had invested a total of $90,000 into the movie (and were more than a little angry with the results, having been promised a straight, bonafide horror movie). So what does he do? He sits on that for a couple of years and then he makes Evil Dead 2. And Evil Dead 2 becomes revolutionary and genre-defining in the realm of horror-comedy—it becomes a horror-comedy on purpose, a redo. Sam Raimi was nineteen when he directed The Evil Dead, the same age I am now. Maybe this is just me, but if I went to a screening of my first feature film (my very scary and genuine horror movie) and people started laughing at it, I’d probably burst into tears. I’d probably never want to make a movie--any movie—ever again. I think that there’s always something inherently vulnerable about making and sharing art; at the risk of sounding cliche, you’re sharing a part of yourself and offering it up for speculation and critique. Art is something that came out of you, that you produced, and even a cheesy genre film like The Evil Dead is art. But Sam Raimi didn’t burst into tears and swear off filmmaking forever—he took notes. He saw how people reacted to his film, he took that in, and he made Evil Dead 2. To me there’s something very humble about that, that I have a lot of respect for. It speaks to a sort of awareness of the other truth about sharing art, one that’s a little harder to stomach: when you share art it stops being yours, even though it's something you created, a part of yourself. The version of The Evil Dead that exists in my head is different from the version of it that exists in Sam Raimi’s head, which is different from the version that exists in my mom’s head, which is different from the version that existed in Stephen King’s head when he wrote the 1982 review that got it a U.S distributor. When you share art you give up your control of it completely, and it takes on not just one life of its own but innumerable lives. Usually that’s not as dramatic as finding out you accidentally made a comedy, but it's still something any artist has to be able to live with, and which I think is a little harder to live with than anyone wants to admit to. All of this is just my observation, of course, and my own feelings on the topic. But Spiderman trilogy or no Spiderman trilogy, Sam Raimi is one of those directors who has an unshakable place in the cultural atmosphere, and one that I think is well-deserved. I really admire him as an artist by virtue of how he seems to be able to reflect on how his own work is perceived, and how he seems to have come to terms with how little control he has over that perception. That kind of skill doesn’t always come naturally, and it's a skill I think is necessary for anyone dreaming of someday getting their work out there. by Clara Sperow Florist’s The Birds Outside Sang album cover

I don’t usually write about music. I also don’t really practice it—in spite of the fact that, over the course of my twenty years of life, I have attempted piano, trombone, guitar, recorder (?), and singing (all for varying lengths of time, with piano at the longest—6 years—and trombone at the shortest—2 months). I don’t even go to concerts now; to be completely honest, a lot of days I don’t leave my house (but that has everything to do with quarantine and nothing to do with my innate, intense impatience and perfectionism). Anyways, I do listen to music, but on top of being an impatient perfectionist, I also have an Aquarius Moon and thus I must be completely original and unique at all times. And I’m sure this factors at least partially into why my favorite band is Florist. If you haven’t heard of Florist, it’s cool. Whenever I look them up, Google thinks I’m looking for flower arrangements, and when I bring them up in conversation, most people blink at me blankly. This normally satisfies the part of me that desperately longs to be original, but recently (in the age of limited human interaction, on the days when I spend the majority of my time making intense eye contact with my roommate’s human-like cat) this has kind of bummed me out. Because although part of me likes Florist because they aren’t mainstream, most of me likes them because I think they’re just really genuinely great. So, this is me writing about music. The last concert I went to before the pandemic really hit was a Florist concert on February 29th at the Swedish American Hall in SF. My roommate of the past three years (who is also my high school friend) went to the concert with me. We did then-normal now-scary things like stand close to strangers in line and laugh without masks on. The venue itself was quirky and fantastic. I walked in expecting to find teenagers standing near a stage but instead found a large wooden room filled with folding chairs, a stage containing a single stool, and lots of different people wearing long dresses and beards. When the opener came on stage, my roommate and I realized it was the band Boy Scouts—an Oakland-based band I became obsessed with my freshman year at Cal and my roommate and I have accidentally seen three times in concert since. In the break between Boy Scouts and Florist, I ran to the bathroom, only to find the lead singer of Boy Scouts (Taylor Vick) directly in front of me in line. I’m an extrovert, but this does not mean I do not get overwhelmed. I opened my mouth, Oh my god hi this is the third time I’ve accidentally seen you perform in the past year I saw you at the Soccer Mommy concert then Chastity Belt now here but I don’t mean accidentally in a bad way I really do love your music the rendition of that uh one song you sang was great I hadn’t heard it like that before and I loved how you *bathroom door opens and Vick hesitantly enters* Oh, how effortless and comfortable communication used to be in the pre-pandemic world. Florist describes themselves as a “soft-synthesizer-folk band and the friendship project of Emily Sprague, Rick Spataro, and Jonnie Baker,” but when it was Florist’s turn to perform, Emily Sprague was the only one who came on stage. She situated herself on the stool with the tenderness of a hummingbird and the energy of my high school English teacher. I immediately felt deeply connected to her. Then, she started talking about an episode of the NPR podcast On Being. I adore On Being, and I had listened to the exact episode earlier that day. Wow, I half-whispered, and my roommate half-chuckled in response. Sprague’s performance was everything I could have hoped for. She sat on the little stool and told soft-spoken stories intermittently between singing songs that I knew by heart. She would introduce songs with statements like This is about how it feels to me to...be in love and I would feel like crying. Overall, it was a beautiful experience, and it’s a nice way to remember how I spent my time when I could go places and do things without the feeling of overwhelming fear and guilt. I would argue a Florist concert isn’t even the best way to enjoy their music, though. They have a Tiny Desk Concert that I watch on a regular basis to calm myself down, to feel a little more connected to the parts of myself I feel at peace in. I also just listen to their music at all times of day, and I have for the past four-plus years. I’ll listen to it sometimes to fall asleep, sometimes when I first wake up in the morning, and sometimes when I’m driving home from the grocery store. It feels right to listen to when I’m taking walks and when I’m cooking dinner. Essentially, it’s exactly what I want the soundtrack of my life to sound like, and if you’ve related to anything I’ve said so far or if you just want a little more softness and calm in your life, their music might be a good life soundtrack for you too. It feels comforting to fill my brain with lyrics that soothe me. When I find myself obsessing, or with a song stuck in my head, it’s nice to default back to lyrics and sounds that I listened to in the first place because they made me feel okay. Listening to their songs feels like you’re simultaneously listening to a nature documentary, a spoken word poem, and a TED Talk with actually good advice. Maybe you’ll listen to some Florist songs and think I have extremely overhyped them, or maybe you just don’t want to spend your time listening to music that feels like nature documentaries, but this is me sharing one of my best techniques to be the most gathered, connected version of myself I can be. I’ve found I need their music more now than ever before. I’ll leave you with some of their lyrics that permanently dwell in the caves of my brain. Light comes from A time already gone If I could see the future I would lay down Eat a tangerine And make a cup of tea Watch it all happen the same way Watch it all happen slow (from “Shadow Bloom”) Please come quick, I've stuck my head in the banister again I've slid and pulled and chafed my neck and I'm freaking out Please come quick, I've stuck my head in the banister again But I just wanted to know what it would feel like With one part of my body alive (from “White Light Doorway”) The mountains around my eyes set on fire before I could even swallow my own spit I was born a boy with many opinions And now I'm a girl who doesn't really care about anything This beautiful thing happens every day It's called the sun It's called my blood And it's the only thing making us want to be alive (from “Thank You”) by Zoe Forest I, like many Roman senators, am someone that would make Cierco roll his eyes, shake his head, and ask what will become of humanity because I’m ready to agree with just about any well-presented idea. I’m especially prone to unquestionably jump on any idea presented by writer and podcaster Malcolm Gladwell, with whom I just can’t bring myself to disagree.

In one of his episodes of Revisionist History, Gladwell explores and defends an alternative form of elections that I couldn’t stop thinking about. At first, I had hundreds of doubts as it goes against everything we’re taught about merit and hard work and success. But the more I pondered it, the more I thought it had the power to revolutionize society for, hopefully, the better. It is… lottery voting (or sortition if you want to sound smart). It’s essentially what it sounds like. All candidates who wish to participate in an election toss their name into the ring and a randomly selected ballot determines the winner. It’s an ancient practice that goes back to Athenian democracy, where this was the primary method of selecting political officials. Though it has been practiced occasionally in other locations and time periods, sortition has yet to take serious hold in any other part of the world. Gladwell was inspired to consider the implications of sorition after reading about a political activist who tested the system in a few schools in Bolivia with incredible results. These schools eliminated the great battle of student council elections and instead invited all students who wanted to join the student council to submit a ballot. The members of the council were then randomly selected and put to work. The councils that emerged from these lottery elections formed some of the best teams the schools had ever witnessed and highlighted some of the advantages to this system. Collectively, the councils comprised much more diverse students than those elected in a traditional voting system and as a result, the student council was made aware of a myriad of previously unseen issues facing the various students. It also encouraged students too afraid to run the opportunity to participate and one of the best council members in a certain school turned out to be a very shy, quiet student who would have been slaughtered in a normal election against far more charismatic and popular students. There was no bias in the selection because there was no selection. No student, no matter how wealthy or popular or charismatic, had an advantage, which gave opportunity to traditionally overlooked students. With various skill sets and backgrounds, these students proved to perform just as well, if not better, than the students traditionally elected and the schools involved benefited immensely. Now, this might appear to go against everything democracy teaches us. These students are being rewarded with no hard work at all! What about their qualifications? What about having a voice in who governs your school? The speeches! The list goes on and on. It’s so fundamentally contradictory to our system. But think about elections and those who tend to get elected. Elections are all about charisma and marketing. Sure, there are platforms and promises but even then the presentation of these ideas often influences voters more than the ideas themselves, especially in school elections. The students with the most charisma or the most friends or the most time to promote themselves are the ones that win, for the most part. Yes, they might be incredible people and they may do a fine job, but the actual responsibilities of a student council member, or a government representative, are not about charisma or having friends. Electioneering and actually governing require different skill sets, and yet we only test the one before making our decision. This prevents highly qualified and skilled students who may be more soft-spoken or less connected or just not interested in the campaigning process from participating in student government. Gladwell adds another point to his support of sortition. People are very poor at predicting success. In a different episode where Gladwell attacks the LSAT, which overwhelmly determines who goes to which law school, he interviews a hiring consultant at a major law firm whose job includes accessing lawyers’ success after they are hired. In his time the hiring consultant has found that the things employers think matter, such as where the applicant attended school, do not actually reflect the employee’s competency or success and yet employers continue to base hiring decisions on unimportant factors. In this episode about sortition, Gladwell interviews the director of the National Institute of Health, a government agency that awards generous and prestigious grants to a limited number of scientific research project each year, and discovers that the ranking system used to rate various grant proposals does not reflect the impact of the research projects once they are completed. The same phenomena occurs within college admissions. High SAT/ACT scores and other factors important in college admissions do not always predict who will be the most successful college student. It may be difficult to hear that us voters fail at predicting who will actually be a good representative or senator or even president, but it’s true. Gladwell proposes how sortition may be effective in various sectors of life, such as grant awards, college admissions, and student councils but stops short of fully exploring the possibility of applying sortition in local and national politics . However, there are several benefits to sortition even when it comes to electing people to congress or the senate. The first is the elimination of party politics. A major reason politicians belong to parties is to aid in elections. But with no elections, politicians no longer need party support. This frees more politicians to voting by their own conscience and judgment, rather than based on what the party supports. Politicians could also avoid falling into the pockets of lobbyists, since they don’t need help in elections. A major concern when it comes to sortition is placing someone incompetent in office. But a few alterations to sortition can reduce this. There could be a preliminary selection process prior to the actual election where candidates would have to meet a set of requirements or voters could select a handful of candidates they would be content to have in the lottery. Or it could be a partial sortition, where some people are selected by lottery and others by traditional voting. The possibility of average citizens aspiring to a political position may also encourage greater study of politics and economics, leading to a greater number of qualified candidates. It may seem far-fetched but many political scientists have written books and research papers exploring the possibility of implementing sortition on a larger scale, showing that it could be possible. People are disillusioned with the current political system. They’re disillusioned with party politics, the influence of big corporations in government, career politicians, electioneering, a lack of diversity. Sortition has the potential to solve those problems. I don’t personally see this ever being implemented on such a big scale as congressional or senate elections, but it’s interesting to think about the positive changes it could bring. And don’t worry, it won’t cure democracy of all its flaws. This system of government still killed Socrates. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|