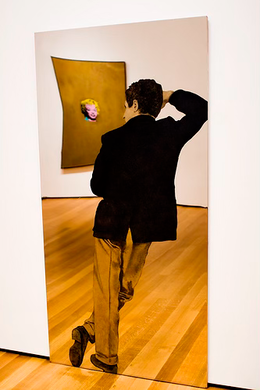

by Sophia Limoncelli-HerwickIn Artifact and Art, Arthur Danto writes that “What makes … artwork is the fact that, just as a human action gives embodiment to a thought, the artwork embodies something we could not conceptualize without the material object which conveys its soul” (Danto 31). I agree that artistic intention and conscious symbolism play an integral role in the creation of “artwork,” but I take issue with the implied notion that artifact, and therefore craftwork, is not artistic. Why should we strip handiwork of its cultural and historical significance because it doesn’t possess deliberate spiritual meaning? Symbolic import may be what makes something a work of art, but symbolism is so intrinsically open to interpretation that anything handmade with the purpose of being at least somewhat aesthetically pleasing can be art. What’s more, as a unique, handmade product of a specific period, every individual piece of craftwork inherently possesses Walter Benjamin’s concept of the “aura” (Benjamin 23). Tenderly brought into existence under particular cultural and historical circumstances, craftwork denies the mechanical reproduction of objects that kills traditional and ritualistic value. Mexican weaving, for instance, produces elaborate textiles that can be worn and used, but the designs of the items also exemplify the specific cultural heritage of each community that the works were made in. Danto’s philosophical experiment in which baskets and pots from different cultures can look precisely the same yet retain different values as art versus artifact further fortifies my point that craftwork can be art. Though distinguished as art objects versus artisanal objects contingent upon their spiritual significance in each respective culture, the fact that they have the same visual, aesthetic properties means that utilitarian objects can be called art. John Dewey and Albert C. Barnes assert that the distinction between craft and art is sufficiently weak and elastic (Danto 27). If we treat art as formal design, as an appreciation of not just intention but simultaneously physical appearance, there is absolutely no reason to exclude craftwork from the realm of art. Denis Dutton asks, “If we treat utilitarian objects as works of art, is it not a mistake because they are mere tools” (Dutton 2)? Though practical use is their primary value, I question the need to make such a harsh division between craftsmanship and art. Does Chinese pottery not serve a similar visual purpose as a Piet Mondrian painting in terms of geometry? Simply because something has a functional purpose does not mean that it cannot be art; many modern art pieces incorporate items that have practical purposes into their work. Consider Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Man with Yellow Pants; he uses a mirror, a utilitarian object, as the canvas for his piece. The practical use is an element of the work, but not the defining aspect. The painting of the man is. This same argument can be used for studio crafts; yes, they have practical use, but they also possess an element of beauty and handiwork that can classify them under the term “art.” Art and craftwork are not mutually exclusive. Why must we perpetuate such a strong boundary between a Pablo Picasso and an intricately woven Yup’ik basket? As Michel Foucault writes in Death of an Author, an artist’s name often applies significance to a piece, but if we forgo the fame of the creator and compare a post-it note sketch to a knit scarf, why is the drawing “art” yet the scarf is a simple utilitarian object? A sketch that took perhaps thirty minutes to complete may be stuck above a friend’s bed, proudly displayed, but the scarf is neatly folded in a wardrobe, hidden away from view until it’s necessary to be worn and used. We fail to consider that baskets, glassware, ceramics, clothing, and countless other studio crafts all incorporate similar amounts of time, dedication, effort, and even aesthetic consideration to construct as any given painting, drawing or sculpture. Let’s say that the scarf took longer to produce than the sketch; just because it’s not a figural or symbolic image, it’s not art even though far more physical effort went into creating something beautiful? Hands created the scarf just as they created the sketch, and to distinguish the scarf as less valuable is to disregard the human nature inherent within anything handmade. Employing the most fundamental level of formal analysis, it’s indisputable that the design and physical production of craftwork makes it art. Sources: Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, 1935.

Dutton, Denis. “Tribal Art and Artifact.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 51, no. 1 (December 1, 1993): 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540_6245.jaac51.1.0013. Stevens, Phillips, Arthur Danto, R. Michael Gramly, Jeanne Zeidler, Mary Lou Hultgren, and Enid Schildkrout. “Art/Artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections.” African Arts 22, no. 1 (November 1988): 18–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3336683.

1 Comment

|

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|