|

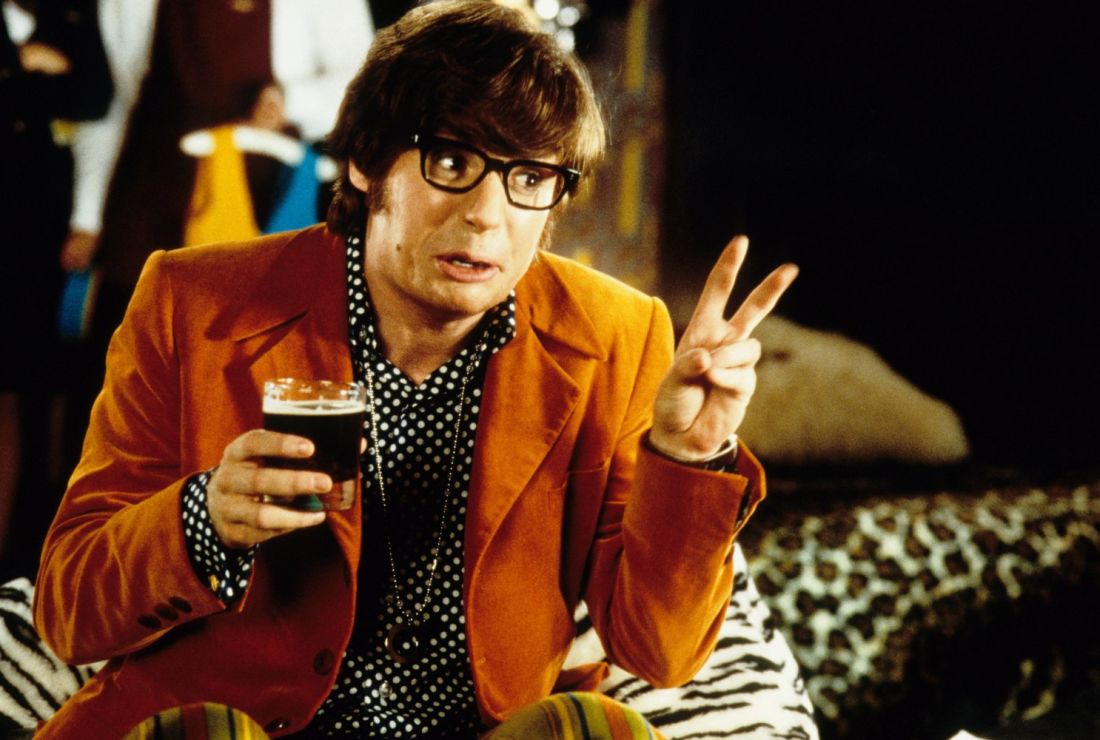

by Truly Edison image via mentalfloss Remember all those Daniel Craig Bond movies? No Time To Die is apparently still coming out...eventually. Evidently, not on any streaming platforms, according to the most recent news from producers. I myself am violently neutral on this newest Bond reboot (if maybe still a little annoyed from having to hear “Skyfall” on the radio ten times a day back in 2012). I could never put my finger on exactly why I didn’t find them particularly compelling; something about them just didn’t click for me, some unidentifiable but obvious element. But recently I came across an article from earlier this year that started putting the picture together for me just a little bit more—it proposed the idea that this newest reboot of the series struggles because it finds itself living in the shadow of parodies and other campy iterations of its genre. Namely, the Austin Powers films. Now, for the sake of putting any and all biases on the table from the get-go, I am an AVID fan of Austin Powers. The first film is easily one of my favorite movies of all time, and that’s movies, not comedies. My high school girlfriend almost broke up with me junior year because I got so obsessed that I started reflexively talking...Like That (groovy, baby ☹️). I read Surrey’s article first because of the selfish fan Schadenfreude that came from the idea that these stupid movies I love were tangibly screwing up a multi-billion-dollar cinematic universe (as well as the obvious dirty joke in Craig’s lament that ‘Austin Powers fucked James Bond’). What I got out of it was a perspective on the whole phenomenon I had never considered before. These modern Bond movies have undertaken an uphill battle: the quest of becoming the ‘serious’ Bond films. They wanted to create a Bond who was nuanced, who had more weight to him than previous incarnations of the globetrotting, womanizing spy. They feared letting the lingering silliness of the character—of the concept—seep too much into their new films. And they definitely didn’t want to get too close to the cultural legacy of Austin Powers. But where I personally think Surrey struggles a little is in his lukewarm expression of just how integral this campy approach is to Bond films—to spy films in general, to be honest. He’s willing to admit that camp might have been “occasionally the intention”, skirting around it in reference to the older films like it’s a bad word or something. I want to take it a step further. In my opinion, these movies HAVE to be campy to work at all; trying to overcome the inherent ridiculousness of the premise is a burden that not only can’t really be shed but shouldn’t be. Like, I can’t be the only person who finds something about all those classic Bond films kind of hilarious, right? I can’t even pinpoint exactly one thing; perhaps some part of it is looking at them in retrospect. After all, in a post-Bond world, they can have a tendency to run like parodies of themselves. Those over-the-top opening credits, all those tropes and cliches we know and love presented as-is in their original context with no self-consciousness or pretense of satire...poorly aged as they are, there’s an undeniable sort of charm there. Even if we go off the assumption Surrey makes that the humor here is incidental, you can’t name a character Dr. Goodhead on accident. I mean for fuck’s sake, one of those films is called Octopussy! That’s the title of a real Bond movie! It’s not a porn parody! Spy movies in the style of James Bond are dumb as hell, and I say this as the most sincere of compliments. If you’re still not convinced, just try and listen to the opening theme for 1974’s The Man With The Golden Gun with a straight face. And taking something like Austin Powers into account, parody is the most natural cultural response to films like these. There’s just so much perfect raw material! Nothing new even really has to be added—all Austin Powers does is crank existing tropes up to eleven and put them in a ‘real world’ to highlight the absurdity. Honestly, I feel like with less time travel and genre consciousness Austin Powers could have run as a fairly-straight series of spy films (and 16 year old me probably would have been just as obsessed with it). Perhaps the easiest way to illustrate what I’m trying to get at here is to pull an example from a more immediately obvious failure: the mid 2010s attempts to revive Superman, particularly 2016’s catastrophic Batman vs. Superman. If you're making a theoretical ‘gritty’, ‘updated’ Superman movie, you’re going to run into one major problem: Superman is, innately, a guy in a blue spandex suit who shoots lasers out of his eyes and dies if he touches a certain kind of rock. And that’s hilarious! If you lean too much into preserving these inherent qualities of Superman, you’ll wreck the intended tone of your film—but if you stay away from them, you won’t end up with a Superman movie at all, just the awkward and over-compensating shell of one. Spy movies, particularly Bond movies, work the same way to me. It’s the parts that are cheesy and dumb that are essential. So in these recent Bond movies, you end up with this almost Freudian return of the repressed as they work so, so hard to hold back the nature of their own existence. It’s how you get cultural oddities like Casino Royale (2006)’s infamous cock-and-ball torture scene (click at your own risk!). As the first of the modern, newly ‘serious’ Bond films, it had the most daunting challenge to overcome—the need to completely define out of the genre the very things that made it. The scene is off-puttingly, and yet hilariously brutal and unnecessary. You can just feel some poor writers going See? See? Bond movies are tough and gritty now. Please don’t laugh at us. Granted, some of that humor comes from the consciously written dialogue, but a hefty portion of it is completely situational. You want to laugh not just at Bond’s shrewd wise cracks but at the whole thing, while at the same time kind of knowing you aren’t supposed to. The need to differentiate inevitably cycles back into absurdity. The harder you work to hold that essential nature of the Bond movie back, the harder it’ll pop up to bite you in the ass for trying to ditch it. It’s inescapable. And why should we try to escape it? Why should we be afraid of a little camp now and again? It’s not a crime to make a stupid movie. If anything, we could use more stupid movies. I get so tired out by the same old cement-gray oh-so-serious vibe of (cue bitter old man voice) Movies Today™. Sure, movies today are ‘good’—but are they fun? That’s a bit of a trick question there; in my opinion, at least, a movie that’s fun is good, even if the movie is bad. And I’d rather have a fun ‘bad’ movie than a boring ‘good’ movie any day of the week. There’s this poor guy in the comments section of that Man With The Golden Gun clip who says “I have no idea why people think this movie is ridiculous. It's one of my favorites.” Take it from your local Austin Powers enthusiast: there’s no reason those things can’t both be true. In the case of Bond films, maybe they even both should be true.

0 Comments

by Truly Edison horror-comedy legends Sam Raimi and the late George A. Romero - via Reddit

Sam Raimi has been one of my favorite directors since I was in high school, so I was really excited to finally sit down and watch The Evil Dead for the first time a couple of days ago. If this makes me sound like a poser, let me set the stage: when I was maybe seventeen years old and flirting with the idea of switching from pre-med to film, I stumbled across this interview he did on Youtube, probably related to some crappy WatchMojo video. In it, he was talking about The Evil Dead, which I’d heard of at the time, but never seen; my mom was a major horror buff in the 80s, so of course she’d talked about this great iconic horror comedy from when she was a teenager. I can’t actually find the link to this interview again, so hopefully I didn’t just spontaneously generate this somehow, but I remember it super clearly because Sam Raimi said that he really hadn’t intended for the first Evil Dead film to be funny at all. He was just as surprised to hear audiences laughing their heads off as were all of the Detroit citizens who had invested a total of $90,000 into the movie (and were more than a little angry with the results, having been promised a straight, bonafide horror movie). So what does he do? He sits on that for a couple of years and then he makes Evil Dead 2. And Evil Dead 2 becomes revolutionary and genre-defining in the realm of horror-comedy—it becomes a horror-comedy on purpose, a redo. Sam Raimi was nineteen when he directed The Evil Dead, the same age I am now. Maybe this is just me, but if I went to a screening of my first feature film (my very scary and genuine horror movie) and people started laughing at it, I’d probably burst into tears. I’d probably never want to make a movie--any movie—ever again. I think that there’s always something inherently vulnerable about making and sharing art; at the risk of sounding cliche, you’re sharing a part of yourself and offering it up for speculation and critique. Art is something that came out of you, that you produced, and even a cheesy genre film like The Evil Dead is art. But Sam Raimi didn’t burst into tears and swear off filmmaking forever—he took notes. He saw how people reacted to his film, he took that in, and he made Evil Dead 2. To me there’s something very humble about that, that I have a lot of respect for. It speaks to a sort of awareness of the other truth about sharing art, one that’s a little harder to stomach: when you share art it stops being yours, even though it's something you created, a part of yourself. The version of The Evil Dead that exists in my head is different from the version of it that exists in Sam Raimi’s head, which is different from the version that exists in my mom’s head, which is different from the version that existed in Stephen King’s head when he wrote the 1982 review that got it a U.S distributor. When you share art you give up your control of it completely, and it takes on not just one life of its own but innumerable lives. Usually that’s not as dramatic as finding out you accidentally made a comedy, but it's still something any artist has to be able to live with, and which I think is a little harder to live with than anyone wants to admit to. All of this is just my observation, of course, and my own feelings on the topic. But Spiderman trilogy or no Spiderman trilogy, Sam Raimi is one of those directors who has an unshakable place in the cultural atmosphere, and one that I think is well-deserved. I really admire him as an artist by virtue of how he seems to be able to reflect on how his own work is perceived, and how he seems to have come to terms with how little control he has over that perception. That kind of skill doesn’t always come naturally, and it's a skill I think is necessary for anyone dreaming of someday getting their work out there. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|