|

by Ryan Simpkins I love lady movies. About ladies, yes, duh. But directed by ladies? Wowzers. My heart flutters.

This list is critical, personal, and most certainly incomplete. Some films I intentionally omitted, due to either my lack of interest, my concern with their politics, or my not having seen them. I’m sure you will read this and find flaws, be it my selection being too western, too white, or that you’re simply not seeing your personal favorite on here. And that is 100% valid. I haven’t seen every film ever made, and while I’m working on it, I would very much love for you to express necessary considerations to add to my ever growing list of films by female directors! I am but an amalgamation of the films I’ve seen and my thoughts on them. I would love for you to help me grow. That being said, I hope you enjoy my thoughts on some of my favorites and check out at least a few. Little Women (1994) dir. Gillian Armstrong Winona Ryder is gay, and I’m in love. Zero Dark Thirty (2012) dir. Kathryn Bigelow I feel I must mention this force of nature of a film, while I cannot necessarily recommend anyone to watch it. It’s intention and themes are heavily debated. I personally see it as a film on the determination of the West to terrorize. The film stars Jessica Chastain as a government agent who does bad things that ultimately lead to a “justifiable good” (“good” defined by the state, for the state, a “good” one cannot justify as such given the context). Some biopics centered on a female lead dealing with war would sacrifice complexity for an idealized characterization. This creates a character who is perfect, "woke", a role model. This idealized role model is unfair and unjust, spreading a harmful logic on the nature of (white western) women involved in war while making a bad movie (i.e. Mary Queen of Scots). Zero Dark Thirty does not do this, but instead paints a brutal image of a brutal figure desperate to win a fight she cannot bear to handle the full implications of. (Note: I should say this was my interpretation of the film. I did not see Bigelow’s most recent film Detroit, but from what I’ve heard about the film’s confused and overtly violent content as well as it’s questionable intention coming from a white filmmaker, this makes me reconsider my initial understanding of Zero Dark Thirty.) Lost in Translation (2003) dir. Sofia Coppola Look. I’m not a big SofCop gal. Her movies are very white with themes that range from borderline to straight up racist. Plus, they’re often boring. I know that. I stand by and fight for that. That. Being. Said. Lost in Translation is one of my favorite films, quietly capturing a young woman observant and ignored. In Japan, she meets an older man who promises to see her for who she is. Two negative people fall in love because they understand their negativities as valid realities. Yes, a white romance with the backdrop of Japan serves a white girl’s feeling of overwhelming introversion, literally lost in translation. Still, I have never felt more seen by a movie as I did when I was 17 watching this one. Mustang (2015) dir. Deniz Gamze Ergüven Turkish film about sisters dealing with being sold off as child brides. Not only a well done take of a political conversation made entirely personal but aesthetically serene. Like Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation or Virgin Suicides, Ergüven uses hazey soft light and brightened natural colors to create a dreamy femininity, capturing a girlhood while the content is often somber. This is an aesthetic very popular among white women with Pinterest boards, perhaps due to Coppola’s influence. Ergüven applies this organic and feminine style taken by white women and uses it to make a film centered on Turkish politics. Little Miss Sunshine (2006) dir. Valerie Faris (and Jonathan Dayton) The invention of quirk. Lady Bird (2018) dir. Greta Gerwig Every single character featured in this film could have an entire film dedicated to them and I would watch each and every one. Leave No Trace (2018) dir. Debra Granik Easily one of the greatest films of 2018. Granik continues her legacy of discovering young female talent as Thomasin McKenzie is a joy. American Psycho (2000) dir. Mary Harron Men suck and women get that, dope. Clueless (1995) dir. Amy Heckerling Another one that’s morally complicated once you think about it, but hey, so is high school. Can You Ever Forgive Me? (2018) dir. Marielle Heller I’m a strong believer in Melissa McCarthy. She’s obviously brilliant in Bridesmaids and in her SNL cameos as Sean Spicer, but she also makes a lot of shitty movies. Most of these films are directed by men (often her husband), and they’re simply not good. That being said, McCarthy is always able to shine through, exhibiting moments of personal intimacy so bold you’ll be like “why is this woman crying in a film about Paula Deen teaming up with girl scouts who start a girl scout terf war, and why am I crying watching it?” Anyways, the bitch is brilliant and never gets a chance to show it. Heller recognized this, connected with McCarthy, and gave us one of the greatest performances of the last year (followed by Richard E. Grant’s in the same film, an underrated artist now finally getting his recognition). Wonder Woman (2017) dir. Patty Jenkins Say what you will I loved this movie and got emo watching the Amazonians. Me and You and Everyone You Know (2005) Miranda July Weird and great. The Babadook (2014) dir. Jennifer Kent I once considered this the scariest film I ever tried to watch. Great metaphors on postpartum, widowing, and being a single mother. But so so scary. Jennifer’s Body (2009) dir. Karyn Kusama This is feminist and I have proof. The Invitation (2015) dir. Karyn Kusama The hardest hitting slow burn thriller I’ve ever seen. Kusama slaps. Capernaum (2018) dir. Nadine Labaki Harsh and long, but worth the watch. Gorgeous and left alone, like Sean Baker’s fictional documentarian style. Labaki is able to pull some of the greatest performances I’ve ever seen from children. Big (1998) dir. Penny Marshall Okay okay okay, this film is obviously flawed in a lot of ways if you think about it too much (too much being at all). But it’s an absolute classic and so here it is. The Parent Trap (1998) dir. Nancy Meyers I literally do not even have to say anything you don't already know. Holiday (2006) dir. Nancy Meyers An adorable female centric romcom that will make you crush on Jack Black. I showed this to my boyfriend and he cried. Meadowlands (2015) dir. Reed Morano Olivia Wilde loses her grip on her sense of self after the loss of a child. Brutal watch. Outstanding debut by director/cinematographer Reed Morano (of Handmaid's Tale fame). Decided to DP her first project as a director. Damn. We Need To Talk About Kevin (2011) dir. Lynne Ramsay There’s honestly too much to unpack here. Postpartum depression; women deemed “hysterical”; male ego, entitlement, and violence; a gr8 cast; eerie as fuck; just watch it. Obvious Child (2014) dir. Gillian Robespierre Romcom about abortion. Fucking cute and fucking funny. This movie made me unafraid of the realities of reproductive health that once paralyzed me. Must see. Persepolis (2007) dir. Marjane Satrapi (and Vincent Paronnaud) Adapted from the autobiographical graphic novel written by Satrapi. A delightful, grounded story on punk girlhood as we watch Satrapi grow to become an independent activist with the facts of war torn Iran surrounding her. This film is badass. An Education (2009) dir. Lone Scherfig I’m a slut for female centric films about age gap romance. And Carey Mulligan. Shirkers (2018) dir. Sandi Tan Inspiring and nostolic. Teenage girls can rule the world, having the ability to make a historical dent without anything to show for it. Will make you want to see the film that never was so badly. Electrick Children (2012) dir. Rebecca Thomas Phenomenal debut by a director capturing an accurate and personal focalization of an innocent teenage girl who wants to grow. Thomas’ résumé has been filled with promising projects (Looking for Alaska, The Little Mermaid) that have locked her in pre production for years, only having directed a poignant episode of Stranger Things and a short since her feature. Free Thomas’ Career!!! The Matrix (1999) dir. Lana and Lily Wachowski This movie is fucking wild, absolutely goofy, and totally cool, opening up people’s minds to simulation theory, androgyny, and those skinny 90s fashion glasses. As you may have read on any fan forum site, the film’s character Switch was originally written to transition from female to male upon entering the real world. This plot point was ultimately cut from the script by the studio, but the actress cast and character designed were very intentionally androgynous. HONORABLE MENTION: Cam (2018) dir. Daniel Goldhaber Cam is a film about a sex worker written by a sex worker (the stellar Isa Mazzei). It’s funny, spooky, sex positive, and aware, completely tuned into its story, characters, and audience. Goldhaber is genderqueer, and I’ll do anything to recommend this super fun movie to people.

0 Comments

by Katherine Schloss Where the heck did memes come from? Open any social media app and you’re immediately hit by memes about everything from politics to celebrities. Every public event is slyly condensed into a little joke that is a commentary on the unraveling of our society. I feel that memes somehow become an ironic portrayal of the darkest fears of Millenials and Gen Z. Through memes it is acceptable to absolutely decimate someone’s character or make a very serious topic into something that somehow commodifies it into a comedic bit for the entertainment of the “woke” masses. Memes bring people together, just as our own university’s Facebook meme page unites the edgy teens for miles around in their common goal to craft poignant pieces on the culture that they mutually take part in.

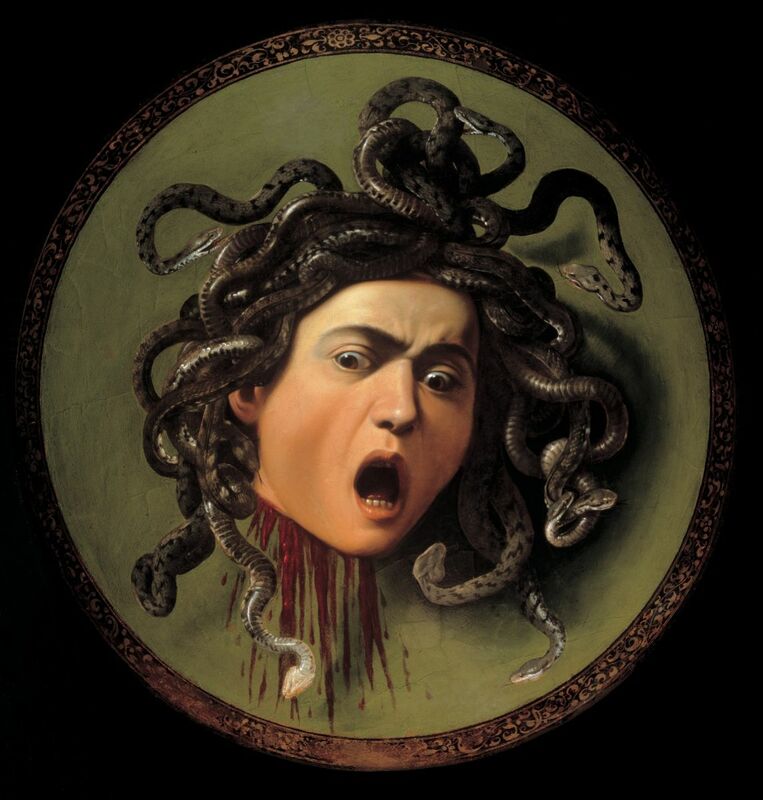

This condensed commodification certainly reflects an ever-decreasing ability to focus on something. Everything must be cut down into digestible skits… like SNL on steroids. On social media, our lives are conveyed by a few words, some strange emojis, and carefully curated content. We create our own little art exhibits, raw and vulnerable and on full display 24/7. What does all of this say about our culture? Are we more aware? Is our ability to curate the things that are happening around us into such a stylized, clean look a reflection of our shallowness, or an increased productivity? I think that memes can be different in that they display a certain agency. While it is true that they can become mainstream, they’re not made to feed their creator’s ego, but rather to facilitate a connection between young people that aren’t willing to take any more bulls***. We are creating our own curated worlds, taking what is relevant to us as young people and crafting a new world within the realm of technology and likes and retweets. This brings about a danger of suddenly becoming unable to care about things that aren’t carefully curated to our taste. Our Facebook feeds spit out what we want to hear, targeted ads hit us at every turn, and our Instagram feed projects the “best,” most aesthetically pleasing and socially acceptable points of our days. Memes, on the other hand, are defined as, “a humorous image, video, piece of text, etc., that is copied (often with slight variations) and spread rapidly by Internet users.” Therefore, this massive amount of consumption that is occurring also allows for a new art form to emerge. The urban dictionary says that memes, “are a lifestyle and art used by teens and adults who are willing to actually live a life that doesn't include depression.” That definition in itself is rightfully meme-worthy. I often hear people say “that’s such a meme” which makes me wonder when people aren’t doing things just so that they’ll be worthy of being commodified on social media into a small picture/text combo. Regardless, I do see memes as a way that we can fight back with comedic relevance against the ever-stressing world that we’re being pushed into. If we can’t laugh at ourselves, we certainly can’t face the confusion of the world that was created by all those preceding us. I talked to two of my friends who make memes for The Free Peach, a satirical publication produced online by students from UC Berkeley. One, my roommate, said, “I find my inspiration from current events, media trends, and the many meme accounts I follow, but also from my friends. Some of the most relatable content is just a result of listening to what people around you are saying.” When asked how meme culture has become so rampant, she replied, “I feel like memes are so loved by our generation because they remind us not to take life too seriously, that everything is a joke, and also of the importance of ~~Free Speech~~.” The other social media editor told me, “I find meme inspo from situations that I am in or have experienced! I'll take a photo and then usually see it's meme potential right away. Or, something will come up in conversation, a person will say something funny or unique, and it will instantly trigger a meme response.” Therefore, memes can be seen as a reflection of capturing spontaneity, in comparison to when one carefully chooses an Instagram photo out of a long string of carefully-staged moments. She said, “I think memes are rampant because they create a sort of standardized and digestible joke. One meme format can be applied to a ton of different circumstances so it's easy to create a middle ground for people. Someone says something and instantly a couple people see it through the lens of memes. Also, memes are spread so fast and there is always new content so it's a form of humor that anyone can dabble in and find something that makes them laugh.” I hope that this post was easy and breezy like the memes that we hold so dear. Sweet memes my friends! by Saffron Sener I’ve never been comfortable with the Greek/Roman tradition surrounding the rape of Medusa by Poseidon in Athena’s temple. As the story goes, Athena became so enraged that Medusa was attacked in her temple that she punished Medusa by turning her hair into snakes. Essentially, she blamed and cursed Medusa for her rape.

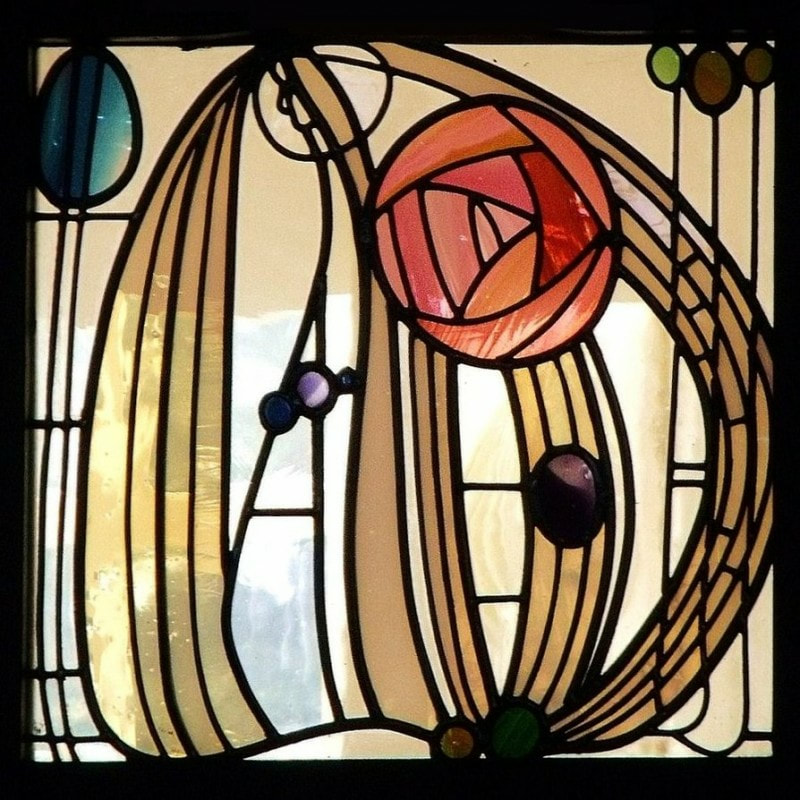

It’s almost like Poseidon himself thought that up, this narrative is so disgustingly male. Ruined by Ovid’s retelling of the Medusa tale and the repetition of this in the centuries following, the story of Medusa that I ascribe to is not one of female betrayal. It’s one of unification, protection, rage, and solidarity. So, I’ve reimagined it here, in this poem: “It was on this stone, your temple, here. Him, Poseidon.” Stand with me. Stand. We must always be standing. Do not bow to me. You may never bow again. The ground is not the place for you or for anyone like us. Raise your head, and look at me. It will be the last time you can, sister. Grabbing, taking, consuming, ruining. The violence upon you is often felt by those like us. (at the hands of my own uncle who is like my father and my brothers and the others. it runs in the family, or is it just their nature?) They pierce. Froth at us. Violate. Walk away with our bodies strewn on ground, See us as open, as the ready sufferer of their desires, entitlement, violence. This is not us. We are not flowers to be picked, lambs to be caught, bodies to be taken. I am giving you a gift Like my helmet, Like my spear. You, too, will have a weapon against those whose existence is protection enough. This head of snakes, biting writhing full of rage and wrath and venom. Not punishment, but security. Not a burden but a blessing, sister. A warning, A curse, A symbol for the pain you must carry for the pain we all must carry. They will run, friend or foe, enemy or lover. This is the gift I am giving you. I am sorry, sister. Go. Look into the eyes of those who pierce and trap them in their disgrace. Remind them from whose body it was that they came and from what body they have forsaken. Relegate them to stone. I’ll shatter them, their ashes will blow across the Earth, forgotten, sent back to a natural place. Where we will walk on them. They will be the dirt where we grow our flowers and raise our lambs. Go, sister, and look. “It was on this stone, your temple, Here. From you, Athena, I become myself, Medusa.” by Akshata Atre The letter K and an apple. When it boils down to it, those are the two degrees of separation between the two images above. But that’s not exactly the whole story. The turn of the nineteenth century was a critical moment for architecture and design. All throughout the 1800s, since the Industrial Revolution, architects and artists were grappling with how to deal with and interpret a newly mechanized society. For the most part, these designers remained trapped in the past, relying heavily on Classical design elements to cover up the nuts and bolts of the machine age to maintain some sanity amidst all this change. Ultimately, however, this masking of steel, iron, and glass became less and less feasible. And, slowly, architects and artists began to embrace the machine age and let go of Classicism. Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1929) was one such designer. Part of the Art Nouveau movement, Rennie began experimenting with new design elements such as bold lines, the whiplash curve, and bright colors. He turned to nature for inspiration and ultimately created work such as the stained glass depicted above. This change in design ideology lay on the cusp of what would become known as modernism - although Mackintosh himself was not necessarily a modernist. However, there is no doubt that his work was influential. Just compare his stained glass work to the iMac computers in the right hand image. These 1990s computers and Mackintosh’s early 20th century art are, arguably, two sides of the same coin. It’s not that much of a stretch to make this claim - just start with the colors. The palette is almost identical. Teal, purple, orange, green, pink. I mean, sure, colors are just colors, but design before Mackintosh was pretty much devoid of these kinds of hues. The most famous European and American architectural monuments from before this era were usually white, occasionally trimmed with gold, dark reds, and oxidized greens. The transparency of the colors too is quite similar, a new quality for both of these pieces in their respective eras.

And then there’s the simple boldness of the curves. As mentioned earlier, Mackintosh makes use of the classic Art Nouveau whiplash curve. The iMac is also defined by a strong curve (what we affectionately used to call a bubble butt back when these computers were the norm), a curve that was absent from computers that came before it. This curve made the iMac friendlier, easier to grasp. Similarly, the whiplash curve was an energetic departure from the severity of Classical design, although it was imbued with a sense of violence. But here’s the kicker: the “Macintosh” was not, in fact, named after Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It was named after an apple, the McIntosh (an apt choice for a company named Apple). But the Mac might as well have been short for Mackintosh - the resemblances between the two design concepts are uncanny. And from a design perspective, there could not have been a Mac without Mackintosh (unless, of course, you think the creators of “The Jetsons,” the actual inspiration for the iMac design, could have started such an art movement on their own). Were it not for the Art Nouveau movement and its proliferation of new, colorful, and dynamic designs, architects and designers might have continued relying on Classical motifs for their work as they had been for the past three centuries. And if that were the case, computers would probably look a lot different than they do now. But that’s not what happened. And thus we are left with a wonderful historical occurrence in which the Macintosh happens to be a descendent of Mackintosh. by Jack Wareham Godard’s films are particularly directed toward proof, rather than analysis. Vivre Sa Vie is an exhibit, a demonstration. It shows that something happened, not why it happened. It exposes the inexorability of an event… Vivre Sa Vie seems to me a perfect film.

— Susan Sontag Here, I want to sketch out and diagnose an aesthetic characteristic of American cinema that I term “American Masterpiece Syndrome.” AMS is not a rare condition. In fact, it affects a diverse and talented group of directors, always male, including Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson, Joel and Ethan Coen, Stanley Kubrick, David Fincher, and Martin Scorsese. Usually contracted later in their careers, these directors become convinced it’s time for them to make a masterpiece of epic proportions – a ‘deep’ meditation on American capitalism, the male ego, representations of violence, or worst of all, humanity itself (whatever that means). The sickness infects their films, which become bloated with pretensions of artistic genius. My goal in this piece is not to criticize these films per se. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Raging Bull, are fascinating. Others, like There Will be Blood and No Country for Old Men, I find vapid and even insidious. I also don’t wish to contest that films like Inception or Apocalypse Now have some moments of brilliance and inspiration. Instead, I’m interested in the urge that these directors have to make ‘epic’ films that cover multiple large topics, vast spatial expanses, and many decades. And correspondingly, I’m interested in the uniquely male obsession with these films in pop culture. What drives men to produce YouTube video essays about the ‘philosophy’ of Fight Club or mansplain the quantum mechanics of Interstellar to you at a house party? Women don’t make these films. They usually don’t write thousand-page novels like Infinite Jest either. There is something undeniably masculine about the imposition of the epically scaled film upon the viewer – a penetrative act that immerses one within the mind of the male director for an extended period of time. Again, I would never holistically deny the value of this category of films. Sometimes, there is a supreme aesthetic object – case in point, 2001. And I couldn’t sketch out a complete alternate framework of what film should be. But I would suggest the answer lies in following Sontag’s evocation of what makes Godard so simple and beautiful. Instead of tackling a massive subject head-on, perhaps film should “[expose] the inexorability of an event,” the essential this-ness of reality, films that only cover a few characters over a few days: Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7, Robert Bresson’s Mouchette, Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie. These are films that don’t over-extend themselves. They begin with the reality of immediate experience, which, after all, is the only thing the artist can truly work with. by Ryan Simpkins I dunno if you’ve seen Uptown Girls, but it’s got everything: early 2000s nostalgia, sassy 9 year old Elle Fanning, peak Brittany Murphy, cute boys, teacup pigs, everything. I grew up watching this film. I idolized Elle Fanning, a young girl who knew what she wanted, who was dedicated to getting it, who wasn’t afraid of telling people off. Plus, she has really cute sunglasses. I kind of assumed this film was a staple in coming of age chick flicks, right up there alongside 13 Going On 30 and Clueless. But I recently discovered so many people that I know and love haven't even heard of this shit. Bitch, we’re changing that right now! It’s free on YouTube! I recently rewatched the film, and not only did I fully enjoy it, I recognized a theme I had never processed before that becomes key to my development as a person: Both leads struggle heavily with their own forms of mental illness, and it is explicit.

Set in early 2000s New York, Murphy plays Molly, an orphaned heiress of her father’s rock star fame and fortune (think Frances Bean but less punk and more Barbie). Dressed in glittering sequins, she's lived her entire life upon a cushion of privilege outside any realm of harsh reality. That cushion is suddenly yanked from beneath her when she discovers her fortune’s been stolen, her penthouse is foreclosed on, and the majority of her social circle begins to push her out of their lives. She is a 20 something child with no work experience. This leads her to nanny for the most impossible child: lil’ baby Fanning. Fanning plays Ray, a child with a track record of disposed nannies, an absent mother, and a father in a coma. She loves organization, hates germs, and must be in control. She has been in therapy since she was 3 and practically raised herself without any consistent guardians. So this fucked up woman child is now tasked with caring for this fucked up old soul baby. Hilarity ensues as these polar opposites discover *~they aren’t so different after all~*. But the film goes deeper than surface level character development of the “odd couple” trope. Both girls have suffered from neglect, and therefore have unexplored afflictions rooted deep in their being. These illnesses are written off by friends and family as “quirky” rather than major ailments that keep them from functioning. Through their relationship, these two young women are able to unpack lifetimes of mental illness via much needed affection, attention, and love. Molly suffers from a serious dissociative disorder. Part of this is likely to stem form her strange fairy princess reality: her parents raised her like royalty only to die and leave her alone with their riches. There's never any mention of who continued to raise her after her being orphaned at 8, though she mentions having lived in her penthouse since she was 2. She has existed in this comfortable privilege since she was young, and it seems as though no one has thought to care for the girl who seemingly had the world. So, she’s used to this surreal isolation and lack of genuine connection. When she discovers her father’s manager has fled the country, taking her entire fortune with him, Molly dissociates. Murphey’s face becomes slack, eyes glaze over. The audio fades out those around her talking reality and logistics. When she comes too and the audio snaps back, she carries a calm smile and ensures everyone that this man will return, even though she knows from previous experience that when people leave, they stay gone. She deals with tragedy via this dissociation, denying a reality she cannot come to understand. She later tells Ray of her reaction to her parents death, a scene I took as outlandish as a kid that I now find very familiar. She staggers to explain how everyone's “voices became a blur” how she “couldn’t even recognize their faces… they became blobs, and then they grew fangs.” Young Molly could not connect with the reality presented and so went into a panic, losing a grip on reality and, as we’re able to see from her outlandish behavior as an ‘adult’, never fully got it back. This is only one aspect of her emotional ailments as her mood swings lead her irrational behavior to drastic situations. Molly sways back and forth between hippie child happiness and enraged desperation. Early on, Molly meets singer-songwriter-sad-boi Neal at a party and believes it’s love at first sight. She takes him home and loves him to pieces as they spend 48 hours in the same room. When he tells her he needs to leave to “rejoin the human race,” she breaks. Moments before their breakup, Molly tells her friend on the phone she needs out, that she’s “not a love machine.” But now he ends it, and despite her statement seconds before, this sends her into a spiraling obsessive depressive episode. She sobs in a couch surrounded by take-out boxes and rotting food. She shows up to his apartment uninvited in the middle of the night. She buys him gifts worth thousands of dollars despite the fact that she is broke. He falls in and out of this relationship, taking her attention until he begins to realize her “obsessive compulsive irrational behavior”. Fast-forward, Neal’s song inspired by his romance with Molly becomes a hit, he's super successful while she’s in the midst of a mental-breakdown. Molly has an episode, running past scenes of connection she has never had (romance, fathers, etc) while Neal’s hit single blares in her mind. She runs to the center of a bridge and climbs the railing, the music cutting abruptly before she jumps to the depths below her. Yeah, Molly just tried to fucking kill herself in this chick flick about babysitting and boy bands. And yet the film flips this into a funny moment as Molly’s head never falls below the surface. The lake is more like a pond. The severity of her suicide attempt build up is done respectfully; genuine for Molly whose characterization has built up to the moment, and the sound mix having us empathize with her anxiety. But what follows is relief met with laughter. Thank god she jumped into a pond of sewage water, thank god she’s not dead. While we’re able to laugh we also stop and recognize the severity of Molly’s state: she is totally alone while she loses her grip on reality. Cue Ray. While far younger, Ray seems to have recognized the world’s realities years before Molly. As she states so clearly, tiny soulless glasses atop her tiny nose: “It’s a harsh world”. And so she copes: trust no one, fend for yourself. If someone bails on you, get angry and move on. Stick to routine and let no one or thing get in your way. Not the most healthy way of coping with an absent mother and “vegetable” dad, but no one has cared enough to correct her. She’s used to controlling her life and tidying things in it so that she doesn't have to focus on the underlying mess of her lack of childhood or abundant loneliness. She compulsively cleans (she carries around her own personal soap bar) and rejects companionship (be it leaving ballet class early or firing any nanny who tries). But once she meets Molly, she eventually accepts change. The two learn to cope. When Molly jumps off a bridge, Ray takes her seriously, nurse her back to health, encourages Molly to heal her issues responsibly. Molly gives Ray the attention she deserves, validating her feelings of loneliness Ray previously rejected. The film balances tone phenomenally, presenting a serious moment where the audience stops for a moment to process what these young women are saying, forgetting that we are watching a chick flick (negative connotation carrying the rotten tomatoes score). And then the moment ends with a laugh- a swinging door to the face, a realization that the protagonist is standing in sewage. This is the reality of mental illness, at least one I can relate to: one moment there's not enough air in your lungs to process the mess in your mind, the next you realize you’re hyperventilating in a Ben & Jerry's bathroom. And that's kind of just funny. I’ve talked too much about this silly film apart of a genre I’ll defend to the ends of the earth, so I’ll leave you with this Brittany Murphy line (rest in fucking elegance, girl): “You know I saw this show once...about all these sick people. And the ones where their friends and families talked to them, they held on ten times longer than the ones left all alone.” And fuck. I really felt that. by Katherine Schloss I’ve never been one for horror films. Sometimes I get unpredictably queasy at the sight of blood, and I often laugh disappointedly at the overly emotional responses from female characters boxed into the limiting role of the victim. Why would I put myself into a situation of simulated stress for two (plus) hours only to find out who the killer was when I can so easily look it up?

But I’ve started to realize that there is a sweet spot between thriller and horror. Create just enough violence and sprinkle in just enough nail biting suspense and you’ve got a perfect concoction. I thought it was worth a try to watch Gaspar Noé’s Climax purely because it was tantalizingly French. Watching Climax was like stumbling through a beautifully lit haunted house, minus the jump scares. There was an uneasiness in that lack. Besides a playful title, Climax was a lot of things. Highly intimate, jarring, nauseating…it was like we were on a drug trip ourselves, with a sensory overload of dancing figures paired with the constantly droning electronic music that became overwhelming in its consistency. The filming style was a couple of long, mesmerizing takes, and it became clear that the film is focused less on forcing viewers to attempt to solve a psychological puzzle and more on presenting life as an ongoing, chaotic dance that we’re all wrapped up in. Cinematographically, the film was beautiful. It retells a (mostly) true story of a French dance troupe that discovers that the sangria bowl which they’ve been drinking copious amounts of at a small party has been spiked with LSD. The film, which was shot in fifteen days and based off of a three page script outline, is enticingly raw with a supersaturated color scheme. Noé’s decision to cast dancers instead of actors-- save for Sofia Boutella-- created very accessible characters and exposed universal truths, despite the language barrier and sparse dialogue. Their dance background allowed for a freedom in which they weren’t overly conscious of their performance character-wise and were instead able to give into their bodily aesthetic. I felt this movie presented a sort of microcosm of the world within which the seven deadly sins were present. Certainly lust, but also envy and the like. The characters all seemed to be insanely aware of power dynamics, and then slowly their social positions began to break down as the drugs set in. Reading some articles about the film, which are bound to be mixed with the good and the bad, I realized that there’s a confusing gray area in relation to the fact that the film is presented as “French made,” in congruence with the presence of a huge, sparkly French flag playfully displayed over the DJ’s turntables. Is the movie presented as notably French? I honestly walked out of it feeling that the disturbing messages were universal, and that the flag was somehow ironically placed and discussed. However, upon closer examination one finds that the first one to be accused of lacing the sangria bowl and to be thrown out into the snow was a Muslim man. Is this a commentary in conjunction with racial unrest in France? The fact that all of the characters are insanely different and that their supposed civility at the beginning of the film devolves and degenerates into a hellish-but highly aesthetically pleasing in the red moody lighting- combination of death drops (dancing term), voguing, and bone breaking intermixed with nervous breakdowns, shaky trips down long hallways, and sex, sex, sex further presents the idea of tensions amongst diverse groups of people. The movie doesn’t have a high point of tension. The line between sanity and whatever else lies on the other side is perpetually blurred with prolonged traipses down hallways, upside down shots, and close-ups of wild eyes. As a viewer you are never truly grounded, as the camera is almost constantly moving and the main character is in a state of paranoia punctuated by bodily outbursts and screams. The camera’s tendency to slowly pan from character to character means that we never quite learn enough about any of them or fully trust any individual character, and are thus presented with the unique ability to make value judgements on our own. The performances are insanely physical and somehow Noé manages to coax out a reveal of the darkness that lies beneath human nature through them. An interesting trope throughout the film was that of the men as a negative presence, giving into their sexual desires and disregarding how the women actually feel. David’s main goal is to sleep with all of the women. Taylor essentially rapes his sister because…incest. The film essentially breaks down male sexuality into a meaningless search for dominance and pleasure, resulting in their reveal in harsh lighting at the end of the movie as a mass of exhausted bodies. The men are presented as primal and crass, and the women are often manipulated despite their strong personalities. Lou is cornered, Gazelle is raped, and Selva is harassed. In the end, Psyche is the one who spiked the punch and watched unharmed, so perhaps a female prevails? However, she ends up giving in to her supposedly regretted past by applying acid eye drops. It is clear that, in Climax, dance is presented as a reflection of life itself. This idea can even be found in the opening bird’s eye view shot of a woman screaming in a bloody, snowing, writhing panic. It is especially apparent when Ivana’s response to, “If you couldn’t dance what would you do?” is simply, “Suicide.” I’ll leave you with one of the intertitles from the film: “Life is a collective impossibility,” which hopefully leaves you spinning around like the fruit in their endless cups of sangria. by Asri Alhamdaputra I’m sick and tired of being the token queer person of color in every space I go to. Here’s an insight to my experience living as a femme non-binary person of color: every time I walk into a room, in an academic setting or otherwise, I feel the need to prove my worth. Namely, there’s always an urge for me to make a statement to the people I share space with that just because “I look like this” does not mean I am incompetent. I feel a constant need to ensure everyone in the room likes me in order to set an example for folks about what it means for a multifaceted complex individual to identify as non-binary. I fear for my safety walking down the street when I am femme-presenting. These are just the tip of the iceberg. Intentional or not, every day I experience some form of discrimination or micro-aggression. But taking that into consideration, my plight as a person of color identifying as non-binary femme is nothing compared to the racism and transphobia faced by Black trans women, to the discrimination and exclusion faced by Black students attending Berkeley, to the racism and sexism faced by Black women.

Last week, I was in the midst of lecture in my film class when a discussion about racism come up. My professor brought up some very interesting points that led to a very engaging discussion with my classmates. Of course, through listening to what people in my class had to say I felt like I learned a lot about the material and how it relates to racial dynamics. However, throughout the whole process I felt two things that are in opposition with each other: 1) I felt compelled to say something to prove my worth to the rest of the class, and 2) I felt uncomfortable and discouraged to participate in the discussion. This oxymoron of emotions came after I took a second amidst lecture to look around; I see that over 90% of the class is made up of white and Asian students. Not a single Black student in my class and I was the only femme presenting queer. Something about that demographic disturbs me to my core. Specifically, how can a group of middle to upper-middle class white and Asian students discuss racism? None of these students have ever experience discrimination in the same way Black people do, nor have most of them ever experience what it means to be the token POC in a room. Thus, faced in a situation where I’m discussing racism in a room full of people who would not understand my experience as a minority, I would feel equally uncomfortable and compelled to educate. The situation I faced in my class is inherently hypocritical because what we are discussing in class does not reflect the condition of the class itself. What use is it to talk about racism if we are excluding Black and Brown students’ access to education? What use is it to talk about racism if it’s not specifically geared toward dismantling and acknowledging your white privileges to a room of white students? How much knowledge of racism can a white professor teach, knowing that they would never experience real-life racial discrimination and prejudice? 3%, that’s how many Black people make up Berkeley’s student body. That’s not at all reflective of how many times racism is discussed in our classes. For me and other Black and Brown folks, the thing about race is: race is not something that is only talked about within the confines of a class discussion. We don’t only think about race when a professor prompts us to discuss it. Race is our reality and we think about it every single day for the rest of our lives. What does this have to do with art? For the people reading this, I want you to know that the curators of BAMPFA are predominantly white. I want you to know that POC’s are doing extra emotional labor in our classes every time the subject of race is discussed. Please understand that Berkeley’s demographic does not reflect the communities it displaces. If you are white, understand that BAMPFA is a white space made for white people to preach about diversity in the art world. The next time you are in a class discussion, look around you, be cognizant of the space you are in. Ask yourself: am I taking up too much space? Understand that students of color interact with the space differently than you do. And lastly, don’t forget to support artists of color, especially those who gave up a lot to be an artist, whose skin color or gender identity or sexual orientation or ethnicity and nationality put them in a disposition where being an artist is improbable, yet against all odds they remain a creative being that makes the world a little less boring. by Saffron Sener Hans Memling, Last Judgment, triptych, oil on wood, 1466-1473 One of the most prominent (and my personal favorite) scenes in Northern European 14th to 16th century art is that of the ‘Last Judgment’. A Biblical story derived from the more apocalyptic portions of the text, the narrative of the ‘Last Judgment’ or ‘The Day of the Lord’ decrees that following Christ’s Second coming, all on Earth will face evaluation at the hands of God. Each person will be determined “good” or “bad”, and from this judgment be sent to Heaven, Purgatory, or Hell. Look to Pieter Bruegel’s 1558 engraving or the ‘Last Judgment’ half of Jan van Eyck’s diptych for examples of the gothic, dark, moody Northern depictive style. Perfectly odd, grotesque, dark, excessively detailed, and absolutely amazing. This isn’t to say that Lower Europe, specifically Italy, France, and Spain, failed to pay attention to this cataclysmic unfolding. Michelangelo’s mid-1500s Last Judgment pays a sunny, heaven-centric homage to the scene. Fra Angelico’s 1431 interpretation is similar to that of a triptych, with Jesus Christ floating above the rest on a throne of gold. La Gloria by Titian in 1554 is a perspectivally-unique, communicative piece that forces the viewer to look upward towards the glory that was Heaven. The divide between the two regions, as it often is, lays within their respective bright or dark natures, in the gaudiness of one versus the brutality of other, their overall styles as according to the sort of period eye (as Michael Baxandall would say) of either place. We can see collective attention placed on narrative across Europe, with a transition from Heaven to Hell often occurring from up to down or left to right, centered by Mary or Jesus Christ. We can also see an adherence to the concepts of the story, with a clear divide and communication of good/bad between Heaven and Hell maintained in both the North and South. However, in the interest of speaking to one Northern European artist’s rendition of the Last Judgment rather than drawing a developed comparison and contrast between the scene’s treatment in the North and South, I’ll point this towards Hans Memling. Born in the 1430s, Hans Memling hailed from the Middle Rhine region. Little is known of his early life beyond his apprenticeship in Mainz or Cologne and subsequent training under Rogier van der Weyden in Brussels. This is where Memling integrated himself in the Netherlandish art scene. By 1465, he was a citizen of Bruges in Flanders. In 1477, he married a woman named Anne and fathered several children. Successful in his career and popular with Italian patrons, Memling enjoyed relative wealth via his artistic endeavors for the duration of his lifetime. He died in 1495. Typically, despite his Germanic background, he is grouped into the Early Netherlandish tradition and movement due to his location throughout the majority of his life as well as stylistic dealings with perspective and spiritual/mythical narratives. The Last Judgment by Memling is one of the artist’s most-well known. A triptych displaying the entrance into Heaven, judgment by Christ, and descent into Hell respectively from left to right, this piece affixes the Biblical narrative into one - a framework of an almost mythical majesty. About ten feet by seven feet, this looming artwork overpowers its audience in its intense grappling with the apocalypse of life on Earth. On the far left is the first panel, which depicts the ascent of those deemed “good” into Heaven. Saint Peter helps the naked, white bodies of the saved onto the silvery, almost crystal stairs that snake up to the entrance of paradise. Immediately in front of the gate, a group of angels clothe the people in deep-hued dresses similar to their own. The gate itself, surrounded by a stormy wreath of clouds, is in a Gothic architectural style and is adorned with reliefs sat in attendance of those entering. Balconies carved into the passage hold angels in bright clothes and with bright wings playing a litany of instruments. If one looks closely, they can see that the Pope and other high-ranking Church officials are leading the procession into paradise; further analyzing the identities of those supposed worthy in the eyes of the Lord, one may notice the seemingly special facial features, implying their potential representation of patrons to Memling. On the central panel, one can see the beginning of this judgment narrative develop. Seated on a rainbow and draped in a red cape, Jesus Christ stares directly at the viewer. His feet - crucifixion wounds on display - rest on a golden orb. Out of his right side grows a flower (a lily) while a red-hot sword points inward at his left. Behind him is a golden light that appears to emanate outward from his body. Kneeling on the same stormy clouds that surround Heaven are the twelve apostles, who extend in placement behind the son of God. At the end of either line of apostles is Mary, who looks to her son, and John the Baptist, who looks to the audience. Above them all, in the upper corners of the panel, are four angels holding the Instruments of Passion (which Jesus utilized to overcome Satan): a column, representing where Jesus was flagellated, the cross where he was crucified, his crown of thorns, and the Holy Lance driven into his side. Below this floats three angels blowing the horns of the apocalypse point inward at Saint Michael. His figure, as well as the rainbow upon which Jesus rests, separates the realms of Heaven and Hell in the location of the Last Judgment, the valley of Josaphat. On his right, there extends far into the background green grasslands, where people are rising from their graves, angels are fighting with demons over individual souls, and the line into paradise begins. On his left, on the dead, brown land crowds of people are being driven backward by the dark, smoky bodies of demons. Saint Michael stands tall above this, using a balance to determine the goodness or badness of an individual. He wears reflective gold armor, a red cape embellished with designs, and a pair of creamy-black wings that flow into that of a peacock. Using his crosier, the Saint jabs any person tipping towards evil and expels them to Hell. Moving to the final panel, one can see the realities of Hell as imagined by Memling. Grotesque, animalistic bodies with tails, taloned feet, and somewhat dog-like faces torture the souls damned to this realm. Their black bodies represent a hybrid between human and creature, juxtaposed upon the writhing, white bodies of the humans sent to Hell. Fires lick upwards in the backdrop of this panel, with flying demons carrying loads of souls into their reaches, almost like they were kindling. Every face of the damned displays an acute sense of suffering, and most gaze away (potentially in shame) or keep their eyes closed. Notice the disjointed amount of people on the two side panels; far more people were sent to Hell than granted passage into Paradise. Above this scene of torture floats the final angel of the trio in the central panel, blowing the last trumpet of the apocalypse. This piece is gripping, intense, and weird. I love it. In a similar strange, whimsical, fashion is Hieronymus Bosch’s 1482 work of the same name. In both, Jesus Christ sits upon a rainbow ring flanked by the pristine glory of Heaven on the left and the everlasting fires and monstrous demons of Hell on the right. The Lord reigns above a land of naked people and brightly clothed angels, running about during a catastrophic sorting of good and bad and medium. For both Bosch and Memling, the story of the Last Judgment provide a narrative by which the limits of illusionism, curiosity, and symbols are explorable. It’s not often that I, as a student of art history, get to just jump into something distinctly in my interests. I find the classes on the Renaissance abounding, courses about contemporary art a constant availability. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing (though I will contend that Art History, on the whole, is a very Western, very White, very elite field). It’s not a great or good thing either, though. I understand that my now extensive experience with Italian art through its ages has helped build the analysis you just read. But I also understand that this analysis is flawed, incomplete, rooted in a knowledge that is almost entirely self-researched and self-taught. Where the institution has failed me, though, I must grow -- it has and is on me to put the extra effort in to explore what I love and what traditional art history tries so hard to hide (I’m coming for you, Picasso and Pollock). To completely conclude this treatise on ‘The Day of the Lord’, Hans Memling, and the strange darkness of Northern Renaissance art, I would like to acknowledge a somewhat more contemporary rendition of the Biblical scene that may or may not be my personal favorite to date. John Martin’s 1853 Last Judgment is wispy, expansive, and quietly captivating. Unified by an endlessly deep void and flowing in a varied, asymmetrical way, this piece is, in my opinion, breathtaking. Noticeably, the perspective is that of someone above Christ and the unfolding of the apocalypse, rather than some positioned below the hierarchy of Heaven and Hell. John Martin, Last Judgment, oil paint on canvas, 1854

|

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|