|

by Lucas Fink

Abby Tlou2 GIF from Abby GIFs

I put down the controller and watch, hypnotized and shaking with anxiety, as the early-20s woman I’ve been playing as for the past 5 or so hours struggles to keep her toes on the bucket beneath her while the noose tightens around her neck. This is Abby. Her face, veins bursting forth from her forehead, is dimly illuminated by the warm glow of a burning car nearby. Another woman emerges from the dense redwood forest just beyond the car, lifts Abby’s shirt to reveal her stomach, and holds a knife up to it: “They are nested with sin”. These are the Seraphites. Before she can disembowel Abby, two men drag a young Seraphite girl into the clearing, whom, at the behest of the woman, shatter the girl’s arm with a hammer. An arrow then flies out from the foliage, followed by another, killing the two men. While the panicked woman shoots blindly into the forest, Abby sees an opportunity and wraps her legs around the woman’s neck. The girl with the shattered arm picks up the hammer and digs its sharp end into the woman’s eye. Abby removes her legs but now hangs freely, suffocating. A Seraphite boy with a bow-and-arrow runs out from the forest, whom the girl orders to cut Abby down. Abby collapses to the pavement, stands up slowly, rips the hammer out of the dead woman’s eye, and turns toward the treeline, from which demonic shrieks echo. “The infected are coming”, whispers the girl. “Stay behind me”, Abby orders. The camera, never having been interrupted by a single edit during this cutscene, centers itself behind Abby, and now, with no transition between the cutscene and gameplay, I’m playing as Abby, about to fuck up some mushroom zombies with a hammer. This is The Last of Us Part II, a video game written by Halley Gross and Neil Druckmann, directed by Druckmann, developed by Naughty Dog, and sequel to what is widely regarded as the best narratively-driven video game of all time, The Last of Us. The game follows a 19-year-old woman named Ellie on her brutal, increasingly hellish quest for revenge amidst a post-pandemic United States. Abby is also in the game(saying more would be a mega-spoiler). The game is really good. So good that I felt compelled to write an excruciatingly detailed summary of one of the game’s most riveting, and grisly, set-pieces. This grisliness, this shocking and often upsetting violence, has stoked significant controversy. In the first TLoU, protagonist Joel’s path of carnage never really feels unjustified up until the climax(the best final act of any piece of media ever), as both his life and that of a 14-year-old Ellie, who’s immune to the virus and potentially the key to unlocking a vaccine, are at stake. Furthermore, the game goes to great lengths to make the combat gameplay feel incredibly uncomfortable and gruesome; when you shoot an enemy with a shotgun and hear their bubbling, sputtering gasps as they hit the floor, you wince and shift your weight on the couch anxiously; you don’t scream “hell yeah epic gamer moment!!!”. In the second game, though, each murder Ellie mercilessly enacts is entirely avoidable, and Naughty Dog ratches up the violence’s gritty, disturbing realism to such an extent that I at multiple points ended up putting the controller down and refusing to play while I paced around my living room to re-center myself. When you kill someone, their friends and loved ones will cry their name in anguish. When you stealth-kill a dog with your bow-and-arrow so it doesn’t sniff you out and reveal your location, you’ll hear an absolutely GUT-PUNCHING whimper and its owner will turn around and cry “LUCY!”. I could go on. I’ve heard criticisms that (A)the game is nothing other than a miserable, guilt-ridden slog through the darkness of humanity’s heart, that (B)the game just “wags its finger” at the player the entire time making you feel guilty, and that (C)its theme amounts merely to “revenge/violence bad”. I’ve also heard criticisms made by reactionary, misogynist assholes who think “Abby’s biceps are unrealistically big” and “queer folk shouldn’t be in this game because games should be apolitical ”; these should be immediately thrown out the fucking window. I’ll engage with the former set of grievances because, while I disagree, they are actually substantive and interesting and warrant a meaningful response. Firstly, the game is not a miserable slog. The horrific, absolutely gutting moments of tragedy and violence are far from the only content the game presents; countless funny, beautiful, and serene respites populate the narrative. Gross and Druckmann don’t brandish carelessly the emotional weapon of tragedy and violence; they use it sensitively and selectively. Secondly, “the game” is an abstract, inanimate noun; a text can’t “wag its finger at the player”. If anything, the game is wagging its its finger at its central characters; they are the perpetrators of these atrocities, not the player. The player is just along for the ride. I can understand, though, why it is so difficult to distance yourself from or to assess unbiased by empathy a character when you control most of her physical actions. The game, though, only allows you to control how the violence happens, not what happens or who gets killed. Often, the game even denies the player control over the how and just presents a small on-screen prompt: “press square to strike”. Naughty Dog didn’t set out to make a role-playing game and as such afford the player absolutely no influence over the game’s events; that’s the point. They’re telling a linear story here via an interactive medium. Thirdly, to argue the writing is lazy because “revenge bad” is the only thing the game has to say is wildly reductive and short-sided. Even if that singular message is the only thing the game communicates, who cares? Classic works of literature and film often boil down to absurdly simple central conceits, not to mention that there’s a vast reservoir of widely-loved texts for which “revenge bad” is really the only theme(Moby Dick, to mention one). TLoU 2 is about identity, perspective, nature and humanity’s existence within and/or apart from it, understanding the Other, cycles of violence, and, yes, revenge. I could’ve just written on all those themes, which probably would’ve produced a more original and insightful post, but a rant in defense of the game is probably more fun to read and I’m at 1,000 words. I'll totally lend you my PS4 so you can play this game.

1 Comment

by Lucas Fink pc creds: a Lucas sobbing in the middle of Work Song I get it; shit got crazy and you were nearly deafened when Tyler finally played Who Dat Boy. Now, having committed you and your friends’ hysteric screaming of “WHO HIM IS?!” to digital memory, that experience is re-visitable. Re-visiting is super cool; scrolling back through your camera roll to find that one video is fun and reveals the nuances of the moment that would’ve been lost to time. You can hear your phone’s speakers falter and hiccup as they attempt to regurgitate those smothering 808’s; you can remember the guy who elbowed you while moshing; you can, to an extent, re-experience the moment.

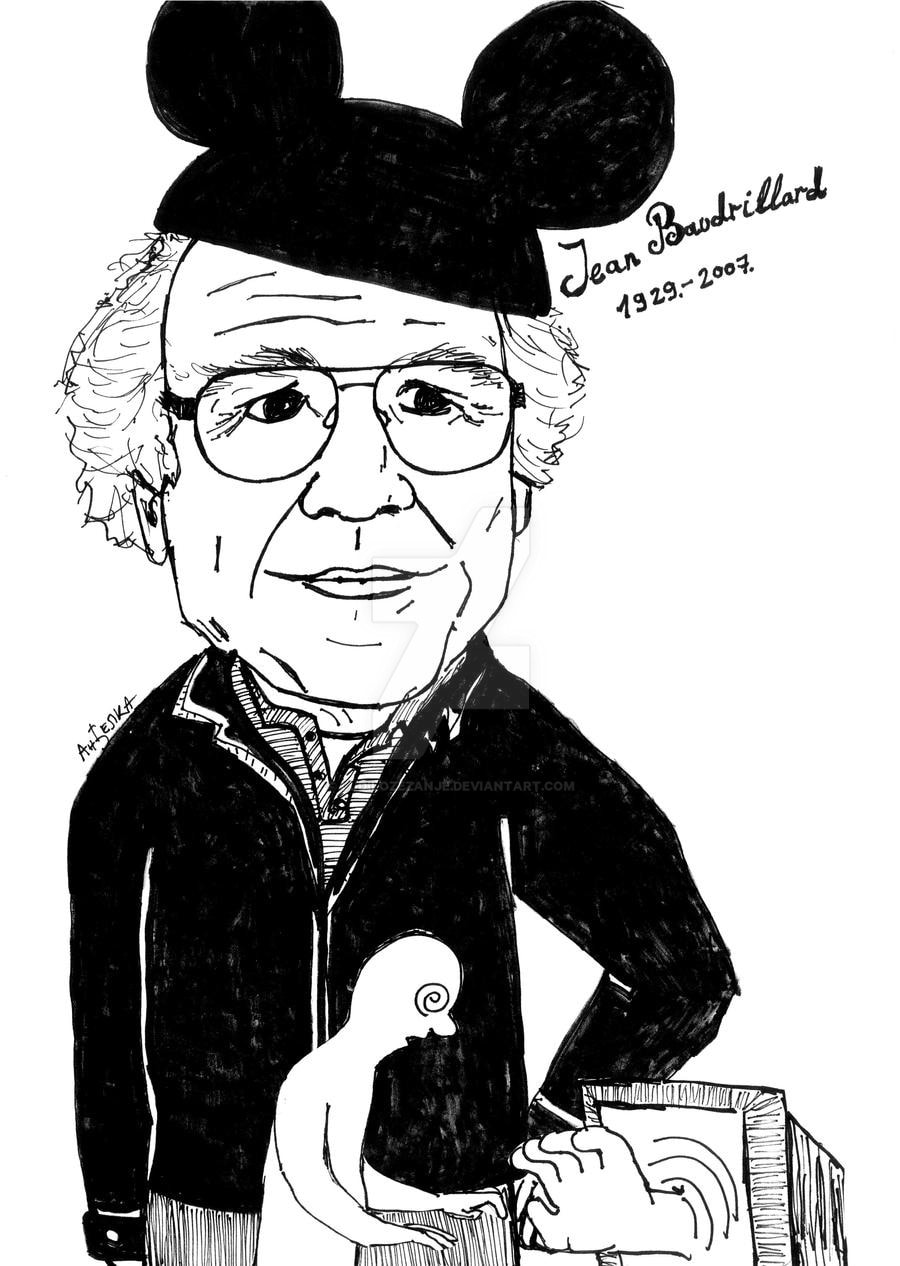

That's all well and good. What I take some issue with, though, is the commodification of memories that the digital realm encourages. I don’t like how social media transforms experiences into products, into mere things to be bought and sold. This phenomenon is specific to late capitalism and has been explained by many smart people - like Mark Fisher, Don DeLillo, and Jean Baudrillard. I’ll try to apply their analyses to those Snapchat stories of concerts you have to hurriedly tap through. Capitalism is really good at turning everything in the world into things that can be bought and sold and into spaces in which buying and selling can happen, and could not give two shits as to whether or not whatever it happens to be commodifying is a papaya or a human person. Deleuze and Guattari call this tendency deterritorialization, the process by which territories once considered sacred - like the human body - are stripped of that sanctity so the territory can be exploited to generate profit. Eventually, capital ran out of physical spaces and things to convert into markets and commodities, so it found new territory into which it could expand: the mind, our private subjectivities. How can it imperialize this new space? It must need nonphysical means by which to conquer nonphysical space. Cyberspace is the perfect tool for capital here, which is why communication technologies have accelerated in complexity at such blinding speeds. Thanks to the internet, your time and intellectual labor have been more thoroughly colonized and your thoughts, dreams, and memories have been newly colonized. This the “information economy”. The internet allows you to share your thoughts and experiences and, as those thoughts and experiences circulate through cyberspace in the form of Tweets and Tik Toks, they take on a life of their own and become commodities. All commodities are, as Guy Debord describes, invested with this spectacular nature, which is to say they try to convince us they’re way more awesome and cool and interesting than they actually are. Once you actually attain, say, the Yerba Mate, it is instantly “impoverished”, losing the spectacular aura and becoming just another canned energy drink dressed up in hip, socially conscious imagery. How exactly, then, do Tik Toks and Snapchat stories operate as spectacular commodities? What are Snap stories selling? They sell you, the idea of you as a hip, indie, cool, cultured, fun-having person that goes to Tyler, the Creator concerts. They also sell the experience of a Tyler, the Creator concert, and of concerts in general. Snap stories convert your experiences into things sold to others as affirmations of your coolness and into advertisements for those experiences. Thinkers like Baudrillard argue that all of culture is like this now, and as a result there are no real experiences, or real anything, anymore. Reality has been totally subordinated to the hyperreal, to simulacra that live independently of their ostensible referents. We care more about the Snapchats than whatever the Snapchats are of/whatever they represent; we care more about making a good Tik Tok than going to the concert and having fun. As a result, Snapchats have become simulacra, or representations that don’t really represent any reality. A beautiful example of the above is in Don DeLillo’s AMAZING book White Noise. In it, the protagonist Jack and his friend Murrary drive past a billboard advertising “The Most Photographed Barn in the World”. Jack and Murray find the barn-which is just a garden variety barn-and, observing as all the tourists frantically snap pictures, Murray remarks “Nobody sees the barn.” How fucking PROFOUND is that? Just as nobody cares about the actual Tyler concert, nobody cares about the barn. The actual barn is dilapidated and boring, and the actual Tyler concert was a stressful, sweaty, smelly, painful mess and after Glitter someone threw up on you. Instead, we elevate the barn to mythic levels of importance by photographing it; as Murray elaborates, “Each photo taken contributes to the aura.” The aura of the hip music scene is similarly bolstered by Snapchats of the Tyler concert, which are beautiful and perfect and only reveal what you want them to. I’m in no way saying concerts aren’t fun; they’re incredibly fun and I miss them intensely and I was just exaggerating the barn-concert analogy. I’m also very much guilty of techno-addiction and as a result struggle greatly with “being in the moment”. Instead of using the concert as an opportunity to fashion a digital fantasy thereof, though, we should just take a couple of pictures and then be there, amongst the sweat, vomit, and everything else. At the end of the Fyre Festival documentary on Netflix, an interviewee notes that a company is charging people to sit in a luxury jet parked on a tarmac and take selfies, and that the company is successful. Baudrillard came up with all the “hyperreal simulacra” stuff in the 1970s, and DeLillo wrote White Noise in the 1980s. They fucking time-travelled. by Lucas Fink (Image via NPR, sourced from EPK. The Bling Ring is now streaming on Netflix) The Bling Ring is an incredibly frustrating 2013 film written and directed by Sofia Coppola. Sofia Coppola, the daughter of Francis Ford Coppola, also wrote and directed the very good 2003 film Lost in Translation. I am choosing to not celebrate her successes as a filmmaker here and will instead foreground elements of The Bling Ring I found to be crass and problematic. We need not be positive all the time. Sometimes movies are not good. Such is life.

The Bling Ring, based on actual events, is about a group of teenagers who break into the lavish homes of celebrities and steal their things. There are three the film wants the viewer to pay attention to. Mark, solidily acted by Israel Broussard and the only character in the film with some semblance of a moral compass, is the audience stand-in. Rebecca, imbued with disturbing callousness by Katie Chang, is an obsessive, borderline-sociopathic kleptomaniac. Nicki, elevated to the level of pure caricature by Emma Watson, is absurdly conceited and obnoxious. They steal from celebrities, enjoy doing so, and are then caught. Such a premise seems ripe for social critique. How does a culture dominated by spectacle, by celebrity, images, and commodities, a culture in which - to plagiarize a smart French dude Guy Debord - direct experience has been replaced entirely by mere representation and appearances; how does such a culture affect the youth who inhabit it? It’s a really good question. Thankfully, the film never concerns itself with it. Instead, the film spends an hour and a half relishing in how ridiculously stupid and vain its characters are. Look at these stupid and superficial teens! YUCK! Doesn’t their behavior repulse you? Aren’t you nauseated and appalled by the detestable behavior of these stupid teenagers? Can you believe that some stupid teenagers actually did this stuff? Isn’t that insane? Imagine being such a stupid, vapid TEENAGER. I’m sorry if I belabored the “stupid teenager” thing. I just felt the need to make it clear how heartless the film is. It’s not just that its characters are “one-dimensional,” it’s that the film ratchets up the one-dimensionality so much that the characters become literal incarnations of all that is evil and abhorrent and then takes sadistic pleasure in highlighting that evil and abhorrence. I should note here I’m not at all against satire or hyper-exaggerated characters. But satire uses its hyper-exaggerated characters to reveal the contradictions or absurdities of the world those characters live in. The Bling Ring doesn’t do that. Its non-characters aren’t used to criticize consumerism or digital capitalism. Instead, they just exist for you to laugh at and be disgusted by. A VICE News Special in 2014 profiles Alexis Neiers, the member of the “Bling Ring” portrayed by Emma Watson. Alexis had an abusive father in her childhood and was addicted to heroin in her teenage years, when the events of The Bling Ring took place. Alexis now writes for VICE about addiction amongst youth and is a certified substance abuse counselor. As should now be apparent, Neiers is a decent person with nuance and depth and trauma. Most people are. Hence my major qualm: the film individualizes responsibility instead of politicizing it. The film’s answer to “why does everyone seem so superficial and vain now?” is “because they’re just like that.” In the final shot of the film, Emma Watson turns to the camera and says something superficial and vain so the viewer can laugh and go “yeesh; people suck.” People like her are the problem, certainly not larger socio-economic forces. The movie is pretty to look at, though. Watch Lost in Translation. by Lucas Fink [spoiler alert!]

Central to Mark Fisher’s theorizations of late capitalism is his emphasis on cultural stagnation and the resultant increase in reliance upon resurrected cultural forms. Nowhere is such a dearth of genuine novelty more apparent than in J.J. Abrams’ Star Wars: The Force Awakens, a film that strays a bit too close to being little more than a beat-by-beat retelling of A New Hope. A force-sensitive teenager on a desert planet is uprooted when she meets a droid carrying sensitive information and is swept up into a galactic civil war, meeting a surrogate father who dies at the end and aiding in the destruction of a massive spherical space station which is blown up after a trench run. I love this movie, but not for its originality. I also really love The Last Jedi, which respectfully and thoroughly inverts the predictability of its predecessor, unabashedly exploding convention and leaving in its wake new vistas of possibility I never thought I’d see in the Star Wars universe. Once every blue moon, the system will glitch and release something so self-aware and subversive that its very existence is one of schizophrenic tension. Why in the hell did Disney produce a movie whose fundamental themes call into question the system on which Disney subsists? I don’t know, but when these glitches in the matrix happen, I get happy. Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi is disillusioned and curmudgeonly, denouncing the elitism and bourgeois hubris of the old Jedi Order as a result of which Emperor Palpatine came to power. Poe Dameron learns it’s okay to defer to a female authority figure and that his self-worth and identity should not be predicated on a toxic conception of masculinity that consists of reckless, selfish, fame-starved individuality. Finn learns from Rose that there is an overclass of absurdly rich war-profiteering assholes who supply weapons to both the bad and good guys and presumably have been doing so for a while, thus helping to produce and perpetuate the cycle of conflict to which the Star Wars galaxy has been condemned for thousands of years. And then Kylo Ren fucking kills Supreme Leader Snoke (also known as Walmart Palpatine) and for three of the most exhilerating minutes in all of cinema we get to witness a fight scene - so well shot and choreographed it’s unfair - between the new Rey-Kylo alliance and Snoke’s Praetorian Guard during which we, while admiring the spectacle, contemplate astonishedly and frantically what in the fuck is going to happen next. Will Kylo turn good? Will Rey turn bad? What do the terms good and bad even mean anymore in this new realm of moral blurriness in which we suddenly find ourselves? Watching that moment in theatres, I felt something I never thought I would feel while watching a winter blockbuster produced by Disney that’s the eighth installment in a franchise: the promise of something genuinely new. Something interesting and thematically rich and shockingly subversive that all the while manages to enhance my appreciation for and enrich my understanding of the characters I’m already familiar with. I felt giddy and surprised and incredibly happy. Mark Fisher was a brilliant anticapitalist philosopher, cultural critic, and continental theorist. He took his life in 2017. Before his abrupt and deeply tragic death, Mark gifted us with some of the most lucidly and passionately articulated theorizations of life in modernity, of life in late digital capitalism. His writings are honest, personal, sad, scathing, funny, and often pessimistic, and yet are subtly - but unmistakably - underlined with optimism, a hope that Mark found harder and harder to sustain. For Mark, life in modernity is characterized by a nebulous malaise, in part engendered by the inability of culture to produce anything actually new. Because capitalism presents itself as the last form of social and economic organization, as the end of history, it evacuates the future. There is no future, because capitalism is eternal and inevitable; it is the way things have always been and the way things always will be. In such conditions, art becomes starved of novelty and as such is forced to become parasitic, leeching off of the trends of the past. If a time-traveller played Arctic Monkeys or The Drums or The Strokes at a party in the 1980s, no one would notice. Nirvana and Joy Division t-shirts are easier to find and purchase than any merchandise from a contemporary artist. Only 4 out of every 10 movies released between 2005 and 2014 had wholly original scripts. The Last Jedi did not have an original script; it was the eighth movie in a franchise now owned by a megacorporation. And yet, somehow, the movie constitutes a rupture in the fabric of the possible. It constitutes the exact thing Mark calls for at the end of his seminal work Capitalist Realism: “The long, dark night of the end of history has to be grasped as an enormous opportunity. The very oppressive pervasiveness of capitalist realism means that even glimmers of alternative political and economic possibilities can have a disproportionately great effect. The tiniest event can tear a hole in the grey curtain of reaction which has marked the horizons of possibility under capitalist realism. From a situation in which nothing can happen, suddenly anything is possible again.” The Last Jedi is that glimmer, that tiny event which shatters the imposed limits of capitalist realism and thus renders anything possible. I wish Mark could have seen it. by Lucas Fink I love Disneyland. I have assembled here a loosely cohesive array of hot-takes on the hallowed theme park, in an attempt to convince myself I can be the next Baudrillard. Here they are.

Fake rust eats away at the fake walls of fake airplane hangars in the area surrounding the legendary Soarin’ Over California, a ride so steeped in nostalgia that the actual ride itself - a raised row of seats floating before a massive rounded IMAX-style screen that convincingly renders the many wonders of our state - ceases to be the primary source of our enjoyment. No longer are my veins filled with giddy, infantile excitement upon seeing the spires of the Cinderella castle towering below my feet at the ride’s conclusion as I turn to my mom and exclaim “That’s Disneyland! That’s where we are now!”. Instead, my veins are filled with a far more potent strain of that excitement, an excitement distilled and intensified by the magic of memory. Disneyland runs on nostalgia. When they brought back the Electric Light Parade, they used the classic synth ear-worm in the commercials promoting it, and only for a few seconds at the tail end of the ad. This is nostalgia weaponized. The selective, restrained usage of the parade theme, other than being proof that these masterminds know just how powerful that weapon is, is designed to merely arouse those memories gently, to pluck them delicately from your subconscious and let your own romanticization of your childhood do the rest. These people are loath to assail their audience with too much tasteless pandering, as they know the Disneyland brand retains that which sets it apart: prestige. Cleanliness. Professionalism. Whatever you care to call it, something about Disney feels high-brow. You go to Disneyland because you know you will be well taken care of and that everything you see and eat and do has been refined to the point of utter perfection by boardrooms upon boardrooms of “Imagineers” infinitely more gifted creatively and intellectually than yourself. Disneyland and its neighboring park, California Adventure, feature several themed areas, each boasting ridiculously impressive levels of detail. Again, this is why we go there. Yet this attention to minutiae does not stop at the terracotta roofing of Buena Vista Street or the creole townhouses of New Orleans Square. Fake rust eats away at the fake walls of fake airplane hangars in the area surrounding the legendary Soarin’ Over California. FAKE RUST. Imperfections are deliberately constructed in a park whose entire reputation is predicated on its perceived perfection. Fake rust at Soarin’ Over California was joined by leaky piping, flickering lights, and dank basements in a decrepit hotel at the Tower of Terror. Disneyland allows its visitors to engage with decay and danger safely. We know it’s not actual rust that has appeared as a consequence of the passage of time and neglect; we rest assured knowing that “the outside world” is far away, out in the sprawling suburban hellscape of the greater Los Angeles area. The approximations of reality Disneyland offers don’t exist to be “convincing” or “authentic”; they function as reminders of the world from which Disneyland offers you sanctuary. They are reminders of the park’s infinite beneficence. Look at the imperfections and horrors from which we shield you! Be thankful that we offer respite in the imaginary and shelter from the “desert of the real”. These imperfections also illustrate the extent to which the forces of capital have appropriated and monetized the appearance of wear and dispossession, both of which are states that people and buildings alike reliably come to occupy under late capitalism. One might justifiably have a difficult time seeing how presenting reminders of the failings of the current socio-economic state of affairs could actually serve to perpetuate that state of affairs. Basically, things that are outside of/exist in opposition to the established order (radical social movements, reminders of the system’s failings like abandoned lots, decay, and rust, etc...) are absorbed by the established order. In the process, they are neutered, so to speak, or stripped of their power to force the established order to yield meaningfully, whether that power may involve reminding the alienated masses of the negative externalities of the market system or expanding tolerance to minorities who have been exploited by the established order. Whatever the case may be, the thing that could be perceived as a threat to the system is rendered “safe”, is defanged, is sapped of political or social potence. All the preceding, which just amounts to a clumsy attempt to imitate cultural theorists much smarter than myself, doesn’t mean that I don’t thoroughly enjoy myself whenever I go to Disneyland. I love it. I revel in the opportunity to experience it, the aura, the atmosphere, the waves and radiation. by Lucas Fink We are in a car with two teenagers and an overwhelming flood of cacophonous music. The camera rotates 360 degrees around a stationary axis in the center of the vehicle, which is speeding down the highway; glimpses of a bright blue sea and sky are seen through the open windows. I knew at this moment that Trey Edward Shults, the writer and director of this flooring, astonishingly beautiful film, was not interested in the notion of “motivated” camera movement, or, at least, not in the traditional sense. Shults’s camera is motivated - just not by the movements of characters or objects of importance through space as is traditional of typical narrative cinema. Shults has opted instead for a camera that doesn’t necessarily show, but evokes. If the goal of the camera is solely to show, to act as a mere relay for visual information regarding the happenings of the story world, then Shults is clearly doing something wrong. Fortunately, Shults knows that the “rules” of Hollywood narrative cinema are arbitrary and restrictive and ripe for breaking. It is to the infinite benefit of the audience that Shults is able to perceive and transcend these limitations and, in doing so, tell a story with a camera whose movements reflect the emotional world of the characters. The wanton exuberance experienced by these two teenagers flying down a freeway, with feet out windows and lips on cheeks, is also experienced by the camera as seen in its perpetual movement; its restlessness and excitement mirror the feelings of the characters. Shults’ strategy is not limited to “positive” moments of emotional intensity; anxiety, confusion, and hysteria are also all “felt” by the camera; these instances of extreme pathos motivate, or animate, the camera just as much as the literal movements of objects through space.

“Narrative” is another notion Shults’ seems somewhat less interested in than his contemporaries. There is a story here, one that is a profoundly moving and important and relevant and beautiful. One might argue, though, that the narrative is subordinated to the style, that the story is a mere alibi allowing Shults to deliver a 2-hour-long sequence of breathtaking shots accompanied by equally breathtaking music, of indulgent audio-visual stimulation. I would argue in response that style here is inseparable from the story. A forward progression through the plot is less obvious in the film, and it often does abandon all sense of narrative momentum entirely. Yet these moments of visual poetry, of slow, wistful contemplation, do further the narrative as they acquaint us more intimately with the characters. This is a film about people, and it sees sound and cinematography as a means by which to provide insights into those characters that traditional modes of storytelling and shot-reverse-shot dialogue wouldn’t allow for. Digital behavior is a tough thing to depict cinematically. Watching a screen on a screen can produce a certain distancing boredom, as I don’t pay to watch something digitally produced, distributed, and displayed to endure even more digital distantiation; such is the effect of “screenception,” as it were. Some films add in post-production CGI (computer-generated imagery) text bubbles that materialize next to the character texting; others situate the viewer in some entirely animated space through which the camera flies that’s meant to embody the digisphere (think Avengers: Age of Ultron). Though these attempts are commendable for their creativity, no depiction of digital life had ever really captured for me the essence of growing up in a digital media-saturated world until I saw Waves. Rather than just pointing the camera at someone’s phone, Shults takes us literally inside the world of social media by employing a transition in which the camera, after situating us in a prom party, slowly pulls back and soon through the cracked screen of the protagonist’s iPhone, at which he glares longingly and furiously. No other moment in contemporary film so elegantly captures the feeling of “wanting-to-be-there,” of missing out, that excessive engagement with social media invariably engenders. Waves is a work of surpassing beauty and brilliance. I left the theatre bruised and cleansed, profoundly sad and profoundly joyous, exhausted and rejuvenated, floored and hopeful. The soundtrack is beautiful and prominently features Frank Ocean and Blood Orange. I loved this movie. by Lucas Fink Sincerity scares me. When the music cuts out in a movie, and I’m to observe the quietly sobbing face of the protagonist, marred by countless rivulets of tears, I get antsy. I get uncomfortable. When the music comes in, and the camera zooms out on the protagonist and their love interest embracing, as the screen fades to black, I get antsy. I get uncomfortable. But when the protagonist cracks a little “wink-to-the-audience” joke to undercut the emotional potency of scene, I feel relieved. Why is that? Metamodernism is a really cool word that refers to the convergence of a modernist sincerity and a postmodernist cynicism in movies, television shows, books, and video games today. The term metamodernism was first used by Mas'ud Zavarzadeh in the 1970s and was substantiated further by Robin van den Akker and Timotheus Vermeulen in their 2010 essay on the subject. The crux of their argument is essentially that the modulation between elements of modernism and postmodernism in contemporary art is suggestive of a departure from postmodernism, and as a result, we need a new term to more aptly describe the current cultural scene. Let’s take, for example, the first Bryan Singer X-Men and the first Sam Raimi Spider-Man films, both of which are unapologetically sentimental and at no point engage in some meta-commentary on such sentimentality. Then we have the Marvel Cinematic Universe of the late 2000s and 2010s, which is, to an extent, predicated on rejecting and undercutting that overt sincerity with Robert Downey Jr.’s signature sarcasm. And, finally, we now have films like Star Wars: The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi, which rediscover an infectious earnestness while retaining that postmodern maturity of their Marvel predecessors. This return to sincerity, mostly unadulterated by a tongue-in-cheek attitude, has not gone unchallenged; a vocal minority of angry man-children on 4Chan have made it their mission to deride every aspect of the new Star Wars films as a response to this tonal shift in their treasured franchise. Many of my peers share sentiments unsettlingly similar to those of the internet trolls, which to me indicates that sincerity is, in the current zeitgeist, no longer the default mode of communication. I notice this phenomenon in myself: in many discussions with friends, the literal meaning of what I say is the exact opposite of the actual meaning; I often use sarcastic inflections to vocalize thoughts or suggestions that I want to preemptively ensure won’t be taken seriously regardless of if I want them to be taken seriously. Sincerity scares me. I want to change that. Postmodernism, I must be careful to point out, is in no way an innately bad thing; it, as a broad philosophical and cultural movement, does not endorse the substitution of Toby Maguire’s Spidey-Sentimentality with Ryan Reynold’s deadpan delivery of fourth wall-breaking witticisms. But the more we see this shift in our art, the more we’ll adopt irony as a primary means of communication. Or it could be that our art is merely responding to an increase in irony in the social scene. Does life imitate art, or vice versa? I have no idea. It does appear, though, that a metamodern shift is our only hope at eradicating this aversion to earnest expressions of emotion, as it may allow us to have the best of both worlds: in metamodern art, like Rick and Morty, a relentless, vitriolic, misanthropic pessimism is balanced by disarmingly sentimental reminders of its characters’ humanity. But, again, I don’t know the solution, or even if a solution to this phenomenon is needed. What I do know, though, is that I miss when moments of collective catharsis, of emotional intimacy with others, weren’t something to be warded off by means of a snarky, self-aware remark. I long to see in the next Marvel movie a scene like Maguire’s Peter Parker suiting up for the first time: the score crescendoing euphorically as the image of Parker admiring himself in the mirror swells with unapologetic and unembarrassed pathos. I’ll end with a quote from the late David Foster Wallace, who says everything I’ve been trying to articulate in the last 690 words or so in just two sentences: “Irony’s gone from liberating to enslaving. There’s some great essay somewhere that has a line about irony being the song of the prisoner who’s come to love his cage.” |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|