|

by Nash Croker What has Critical Theory ever done for us?

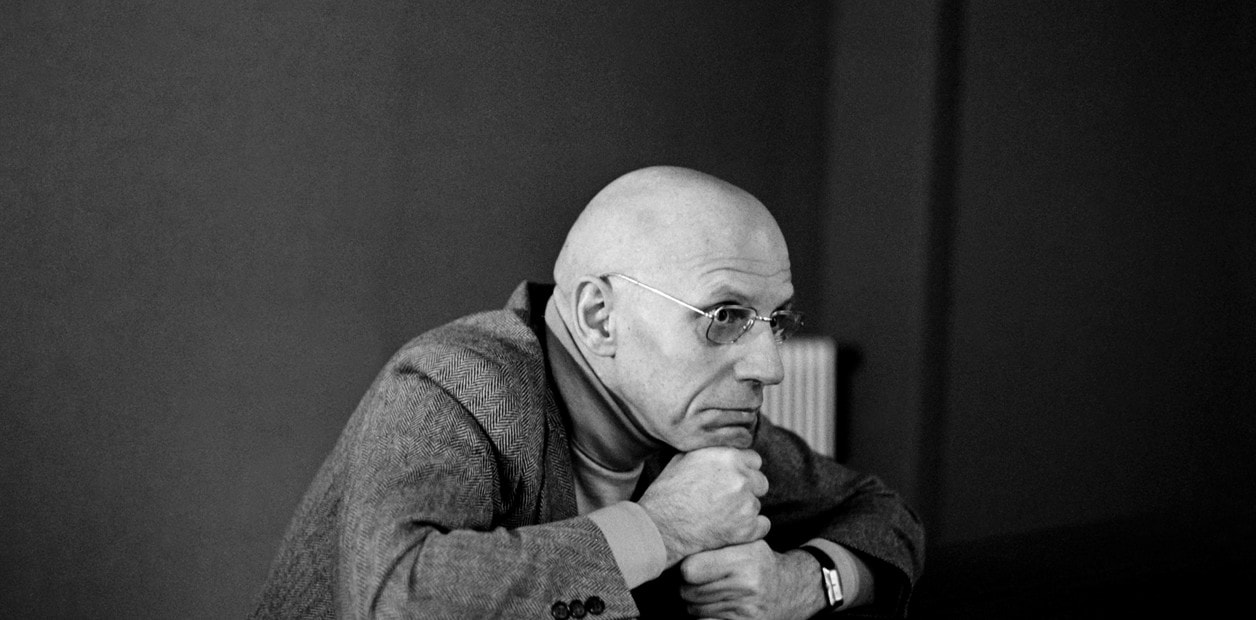

Alright, well, apart from denaturalising sex and gender, the Panopticon, psychoanalysis, defining race as a social construct, Hermeneutics, Semiotics, the labour theory of value and cultural hegemony...what has it ever done for us? Look, I love a Marxist-Feminist analysis of some shitty Netflix show more than the next disaffected queer. But, honestly, sometimes it feels like the most relevant any of this high-minded mumbo-jumbo will get me is a self-satisfied Twitter takedown. Beyond simply trying to understand what Butler, Althusser or Benjamin are trying to say, half of the struggle is making any of this is relevant to lived experience. I truly am glad that Berkeley’s Rhetoric department caters to this academic focus on critical theory. It really is a valuable and interesting interdisciplinary degree focus. Seriously, though, have you spoken to a Rhetoric major for more than two minutes without them name dropping Foucault, Heidegger or slagging off Freud? So much as the denigration of Arts and Humanities in favour of STEM means the small, awkwardly titled department might feel a bit misunderstood, it must be aware of its own pretentions. The modern neoliberal university may not value this field. Funding is not plenty and career prospects even worse. But the old-skool academic rigour of being plunged into purposefully dense texts - maddening until explained in class, written almost entirely by white men in the late 19th and 20th Centuries -means that, functionally, Critical Theory is an exclusionary discipline. The books are often the most expensive in the bookstore (£25 for less than a hundred pages of Guy Debord shitting on TV!?). Not only are the texts so referential of other theories and authors that you really need to have read them all to read just one, but discussions of the ideas within them are mystified in the logics of the field itself. Too often Critical Theorists appear to only be talking to each other. If ever there was an exclusive club for those with the money, time, and access to buy, read and engage in high-minded debate, then it is the school of Critical Theory. “Ok, so what? You’re deriding the theory bro now. Haha, where’s his praxis?” As, my allusion to that famous Monty Python skit suggests, Critical Theory is actually pretty relevant. The problematisation of social movements is vital if we are to see change that does not leave people behind (see applications of Intersectionality in modern racial politics). But as a discipline it needs to be more open to those without this gentil sensibility and security. Rather than working on fine-tuning debates between German philosophers, can we work to make Theories accessible to those without a costly Masters Degree? The elitism of the discipline is no wonder the Berkeley Left often feels stuck in a daydream of the 1960s. Barthes and Derrida are never going to save us. Making this important work accessible and acted upon in our justice movements may well, though. To do so may mean a few bearded Marxists get off their high horses and stop arguing with each other over posh dinners. If the Frankfurt School was so successful in deconstructing the ideology of the culture of capitalism, then why has this politics been allowed to develop its own kind of privileged, apathetic, political culture? Too many men on the Left are afflicted with cultural nostalgia for the radicalism of the ‘60s. Yet to ensconce yourself in the kind of political culture is to lust for possibilities that do not exist anymore. It is to fall foul of the kind of individualism that failed the New Left. Neoliberalism, gentrification and police militarisation mean 1968’s ‘Year of Revolution’ really only spelt the end of Social Democracy. The Civil Rights Movement won its successes (albeit limited) in white northerners willing to die in Southern violence, not through Dylan songs. Copiously reading through the political philosophy of that age, scouring Spotify for these protest songs is to individualise a political culture that is irrelevant today, if not a grave failure. The University and the world has changed. So too must the Left’s political and academic culture.

1 Comment

by Nash Croker Well, not exactly...

As a British Indian it is not surprising that I love the BBC sketch comedy show ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ (1998-2001). What is surprising is that I have only just started binging it. This Blair-era show created by and starring Sanjeev Bhaskar and Meera Syal, set a new standard for subversive comedy, turning racist caricatures on their head to tell a much needed tale about British life. I have normally thought of comedy as fundamentally cathartic. The compulsion to laugh at an observational joke serving as means to dissipate one’s anger and frustration. Sure, it cheers us up, but politically it is never going to change the world. Too often even political satire offers a politically harmless outlet for our very real world frustrations. The revolution won’t happen on SNL. If you are looking to make a political point through comedy, then getting a laugh needs to be your ambition. It is in this way that comedy can be a highly effective means of changing political culture, even if it fails to create any direct political change. ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ and its ability to get us to laugh at what its sketches are saying is precisely how it enacts its cultural political intervention. That of representing British Indians as a constitutive part of British society. What the sketch comedy of ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ performs is a sort of ‘brownface’. These second-generation immigrant comedians put on the racial stereotypes applied to their parents. Contextually this is no surprise. As the largest minority in Britain, many Indians migrated to the metropole during colonisation, most significantly, following Britain's post-WWII drive for immigrant labour from the Commonwealth. A generation later, Tony Blair’s New Labour government came to power in 1997 riding a wave of multicultural optimism based on a boom period for the economy’s financial sector. For a brief period, people of color didn’t have to blamed for the nation’s economic stagnation. And for the first real time on public television, people of colour could have their own comedy show, even if it was still limited to making jokes about being brown. Recurring sketches include the Coopers and the Robinsons - two British Indian couples competing to see who can appear most Anglicised, the superhero ‘Bhangraman’ or the pair of competitive Indian mothers. All of these sketches play on the integration of British Indians into British society. Fronting commonly recognised Indian stereotypes to highlight their inaccuracies by poking fun at their implications. ‘Bhangra man’s’ arch-enemy is the ‘Morris Dancer’, invoking a clash of civilisations so ludicrous so as to ridicule any fear of cultural invasion. My favourite sketch is the “Everything comes from India” man. Here, an excited college age son tries to tell his father about the British history and culture he is learning, only for his father to nonchalantly retort that of course his son is enthralled, because “it’s Indian!”. These seemingly laughable assertions attest to first generation immigrants fear of their children losing their own cultural heritage. The father’s reasoning is based on racial stereotypes - Jesus is Indian because he worked for his dad and managed to feed 5,000 people with a small amount of food. Yet beyond just pointing out stereotypes and attesting to generational differences in immigrant households, by defining traditional British cultures as Indian the sketch acts to educate on Indian cultural influence in seemingly accidental truths (many English words come from Indian languages). The best of these is when the son takes his dad to a Renaissance art gallery. Da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ is actually a portrait of Mina Losa, a Gujarati washer-woman by a painter in Faridabad. It’s obviously ridiculous, but it’s not a cheap joke. When the son describes her expression as “asking us whether we are observers or voyeurs” the father rubishes his claims, “she’s asking how much does this painter change because my brother can get cheap paint”. Implicit here is a Marxist critique of Western art criticism itself, amplifying the economic relations inherent in the production of artworks. Up next is Da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’. Indian, of course, because it depicts twelve men sat around a table for dinner - “where are the women?”. On one level it is playing up to Britain's moralising perspective of Indian society as more patriarchal and thus unenlightened. And yet, here is a principle artifact of the cultural precedent for the Enlightenment ironically being shown to be just as patriarchal and seemingly primitive. The son then moves through as many big names of European art that he can muster - Donatello, Rafael, Tischen, Picasso, Lowry, Reuben, Botticelli, Michelangelo. His father’s silly claims to Indian-ness are once again only half the story. Here the show is highlighting how Eurocentric the canon itself is as well as the developments of artistic form made by and presented in Indian art. The sketch concludes with “the representation of the physical male perfection”; Michelangelo’s ‘Statue of David’. Crucially, however, according to the father, it’s not Indian. Why? Because of David’s small penis. The colonised subaltern was seen as emasculated by the imperial white man. Here, however, white Western masculinity is emasculated by its highest art. It is a slight break from the racial stereotypes of the sketch, but this little truth serves to ridicule the caricatures themselves. It is then how this comedy can evoke laughs from racists and British Indians alike that makes it so effective. On one level it seems as if brown people are making fun of their own otherness, yet on another British society’s racist attitudes are ridiculed by employing the ‘brownface’ mask of racial stereotypes. It is in this subversion of the racial caricature that ‘Goodness Gracious Me’ managed to make some of the most pointed critiques of British society. All while representing British Indians in a public broadcast comedy show. For one like myself, it is the show’s ability to highlight just how Indian Britain really is, reclaiming British identity, that makes it unequivocally some the nation’s greatest ever culture. by Nash Croker Susan Sontag tells me that Vivre Sa Vie is a ‘demonstration’, so I will demonstrate for you the life that I live. If a film can be ‘proof’, then so too can this essay. “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within” - James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1964) For all the sexuality, Jean Luc Godard explicates a musing on the problem of language in his 1962 film Vivre Sa Vie. As we watch a ‘demonstration’ of Nana (Anna Karina) living her life in twelve tableaux; leaving her husband, attempting acting, entering sex work, and ultimately being murdered - Godard interrupts with several textual allusions. From Dreyer’s 1928 classic La Passion De Jeanne D’Arc, to Poe’s The Oval Portrait (1842), it is difficult to see how these textual references do not comment upon the action of the film, at least to forebode Nana’s death with a wink and a nod to the well-versed viewer. Godard is undoubtedly a writerly film maker. Much can be said to the way his films lack interpretation or analysis of the ‘proof’ he exhibits. Yet, so much as he shows with his own camera, he tells with his use of texts. Before her eventual death, Nana embarks on a debate with the philosopher Brice Parain in a cafe. Unlike the others, this interjection into the plot does not appear to comment on the events of the film in so far as it is a commentary on film itself. She asks if one can live without words, but talking is thinking and thinking talking, for Parain there is no life without thought and thus - words. One then cannot speak well without first speaking poorly. Crucial less to Nana and more to Godard, is the problem of language explored in this Parisian conference. Language itself is a poor imitation of the profundity of thought, yet thought can only be expressed in language. Godard’s films may be full of language, but they typically lack an overbearing commentary or authorial voice. Instead the ideas expressed span in scope well beyond the film itself. Godard as director, then explores the problem of language through film itself. The 90-minutes or so he creates can never truly encapsulate his vision and the ideas entertained within them. Like language, Godard’s films are a formidable if poor imitation of ideas. In their own way, his use of texts help to bridge this fact, interjecting others’ ideas into his own to expand his film beyond the film itself. More so than an attempt at reconciling Sontag’s view of a film that cannot not feel like a morbid moral to his own wife - she will die for living her life - however, is the application of the problem of language to subjectivity. Nana’s philosophical debate is part of Godard’s musing on prostitution - passionless sex - as a betrayal of consciousness just like language. Like Nana’s (Karina’s?) life, the link is cut short, but it is better explored in another favourite; Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966). Here, the problem of language becomes that of the problem of subjectivity. Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) is a celebrated actor, yet midway through a performance she stops. This ‘breakdown’ leaves her silent and in the care of Alma (Bibi Andersson), a young nurse. Elisabet’s career is in the performance of roles, but what then or who is she? Her realisation of her own performative existence (that we are all acting out roles) becomes her ‘breakdown’ into silence. Language is a betrayal of consciousness, is a betrayal of her consciousness - so she shuts up. Yet, to not speak is to deny oneself an existence in the world. Spivak’s ‘Subaltern’ springs to mind. Speaking is a primary route to sociability, it is how many of us communicate with others. Yet to be social requires not just a voice and thus language, but a subjectivity through which to make oneself legible to another. Language demands a subject just as sociability requires subjectivity. As Elisabet retreats into silence she becomes increasingly lonely, separated from her husband, swept off to an island in the sole care of her nurse. But by now it has already become clear that it is Alma who is the real patient. Elisabet’s ‘breakdown’ occurs before the fact of Bergman’s film. Encased in Elisabet’s silence Alma opens up about her truth. She likes her job and her husband, but there is always other enticing possibility beyond the comfort of the role she has drifted into. While she has reassurance and respectability in this path, this social security comes at the cost of subjectivity. As she recounts the frivolous pleasure of a spontaneous beachside orgy we are made more aware of the costly marital sex she had later that same night. The weight of subjectivity chosen by and for her elucidates her breakdown, facilitated by Elisabet’s silence and her own words. “I’m so tired of subjectivity” - Jenny Hval, Female Vampire (2016) This problem of subjectivity, however, is really a problem of love. Love requires sociability and thus subjectivity. To give oneself to another requires one to be someone or something to give. To be legible in the eyes of a lover is to have a subjectivity that they can perceive. Do we love our image of our partner or who they really are? As Fanon’s ‘Fact of Blackness’ makes plain, these social subjectivities are a stifling process of assuming the role of ‘Other’. Too often to claim subjectivity, to be legible in the eyes of a lover, is to deny one’s self, is a betrayal of consciousness. Love then is just another process of ‘Othering’. Yet to refuse, as Elisabet Vogler’s fictional existence shows, is to be lonely, to be no one. Crucially, Bergman’s film takes a turn. Alone on the island, these almost indistinguishable women stray into one. Sat opposite on a table, Alma recounts in horrific detail the tale of Elisabet’s motherhood. Twice. The second time we see Elisabet’s anguish at the revelations of her innermost conscience from some other who had no means of knowing. In this moment the two consciousnesses become one as Alma essentially speaks for Elisabet. Alma violently recoils, claiming not to be like her, slapping and then sucking the blood Elisabet’s pressured nails released on herself. If there is consummation of love in Persona it is in this violent scene, fighting is fucking for two queer subjects trapped in the confines of their subjectivity - it is through fighting and breaking norms that queer identity is reified. It is this bleeding of consciousness, however, that seems to offer something on love. Alma becomes Elisabet by truly understanding her from within, she inhabits Elisabet’s consciousness. Elisabet then comes to recognise herself through someone else. She has silenced herself to not betray her consciousness, but now her consciousness has betrayed her through another - Alma. The subjectivity expressed in Alma’s account of Elisabet may be traumatic for her to hear, but only so far because it is true. The subjectivity is not false, she is interpolating herself through another. Love then, as a bleeding of consciousness, as an understanding without words, speaking through each other, is to interpolate one's own self. Love in Persona is less about becoming, and more about recognising and identifying yourself through someone else. Elisabet hails herself through Alma. Love acts as desubjectification; taking off “the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” “...I’m only interested in people engaged in a project of self-transformation” - Susan Sontag, Journals and Notebooks (1964-1980) So much of existing in this world is a process of (dis)identification. Forming the self through identifying what I am not; heterosexual, gendered, white, american. Yet when you exist in a state inbetween legible subjectivities this process is doubled to challenge even the possibility of belonging; not heterosexual not homoseuxual, not male not female, not white not brown. To exist then is to embody a constant process of self-transformation. One does not then take up subjectivity or reject it, but search for recognition in another’s identification of myself as between legible subjectivities.

In this way, love is life and death. In love I am not seeking myself, but identifying myself through another - I belong in and to them. I long for another to see me for who I am. Love is about learning to love yourself through another because you cannot love yourself alone - because if we are not recognised, if we do not speak, then do we really exist? Godard’s film opens with an epigraph from the French philosopher Montaigne: “Lend yourself to others and give yourself to yourself.” There is something to love and the search for it in this quote. Back to Parain in the cafe, Nana must fail before she finds what she is after, there is no going straight for the truth. Love then, too, is a constant project of self-actualisation and self-realisation. One that involves failure but through the right eyes may unerringly be true. If belonging is what we seek, then perhaps we can find it in love. ‘Let's get this guilt’: Exorcising white guilt at ‘The Breadwinner’by Nash Croker At the end of my first month in America, on a whim and a 3-month-old recommendation, I headed down to BAMPFA for an all-age matinee showing of The Breadwinner (2017). Nora Twomey’s adaptation delivered a beautifully animated tale of humanity in the face of brutal hardship. A story, mirrored by its own childlike meta-narrative, of a young Afghan girl (Parvana) who dresses as a boy to care for her family when her father is arrested by the Taliban.

For a story so obsessed with the power of storytelling, however, it was only upon hearing the theatre erupt in applause upon its conclusion that the political role of its own story became apparent. Deborah Ellis, the author of the book the film is based upon, is a white Canadian woman. Nora Twomey, the director of the film, is a white Irish woman. Angelina Jolie, a celebrated white American actor and filmmaker, is an executive producer of the film. The audience with whom I watched the film were predominantly white students of an American Public University. To state these facts is not to condemn these people for their whiteness, their gender, their nationality or their relationship to the production of the film. Instead, it is to locate the production and reception of this story in structural power relations. As soon as its storybook visuals unfurl the first thing to notice about The Breadwinner is the language. With no subtitles and only a scattering of Arabic, The Breadwinner is fully voiced in English by a cast of largely migrant-Canadian actors of colour. This choice immediately asserts that the film and this story are for a Western audience. Unashamedly, The Breadwinner is a film about brown people, made by white people for white people. As such, the power relations between the film’s subject and its intended audience are central to the production and reception of the story. The story is one of persevering humanity and acts of love in the face of devastating material hardship. Yet the causes of this material hardship are intentionally left unexplained. So much of The Breadwinner is about the power of storytelling, and it is through the artifice of storytelling that the film simplifies and obscures the ‘real-ness’ of this fictional version of reality. Even as a cinematic adaptation of a young adult novel the simplicity of its storytelling and eradication of Western intervention in Afghanistan is so severe as to question its political motivation. Kabul’s decline and the rise of the Taliban is left explained only by ‘an invasion’ and civil war in Parvana’s father’s story. This simplified tale is not for her, but for the white Western audience. The childlike frame of reception evades any notion of Western influence for the material hardship our protagonist finds herself in. There is no exposition of the CIA’s arming and financing of the Mujahideen during the Soviet invasion, or the ongoing war in Afghanistan preceded by the US invasion in 2001. Instead, the ‘war’ that breaks out near the film’s conclusion is left woefully unexplained. The plot itself is also mirrored by Parvana’s own tale, told to her younger brother, of a boy determined to overcome an ‘evil mountain elephant’. This use of meta-narratives to augment the main story highlights the film’s own political role in providing a naive simplification of decades of Western intervention in Afghanistan and the Middle East. So much as Parvana treats her brother to a storybook retelling of the plot, The Breadwinner treats its audience to a guilt-free moralising tale of human hardship. Furthermore, as a review of the film in Variety magazine asserts, it is not only through simplified meta-narratives, but through the use of animation that The Breadwinner avoids confronting the human reality of its subject. “If “The Breadwinner” were a live-action film, it would be virtually unbearable to watch, but as animation, it’s not only possible, but somehow inspiring to immerse oneself in this pared-down adaptation of Deborah Ellis’ well-regarded young-adult novel” (Variety, November 2017). Not only does the animation mask the real human face of its fictionalised subject, but combined with a use of English language the white Western audience does not confront a real life Afghani population. In its own way, the animated, voice-acted characters in The Breadwinner are a Westernised fictional creation, substituted for the actual faces of this material hardship. Ultimately, it is only upon witnessing the audience’s own collective reaction to the film that its political machinations become apparent. So much as the animated characters are meant to mask the human Afghani subject, they allow the Western audience to better empathise and see themselves on screen. Not only does the film’s title apply a Western capitalist conception of gendered division of labour, but it takes a markedly Western feminist portrayal of Muslim women’s experience of the burqa. For 94 minutes then, the audience is immersed in an albeit sanitised experience of material hardship. Upon its conclusion, the clapping that follows does not serve to thank the producers and cast of the film for their art. Instead the only witness to the applause are other cinema-goers. To clap at film then is a self-serving act, one that signifies one’s own appreciation and public reputation in relation to the film. Applied to the veritable de-politicised story of The Breadwinner, the audience applause serves to both show the personal importance of having experienced this tale of hardship while simultaneously pulling them out of it, reasserting their privileged status as beneficiaries of the violence to which this material hardship owes its construction. In essence, the political role of The Breadwinner’s story is a cathartic exercise of white guilt. It is the audience’s realisation of this that is expressed in its applause. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|