|

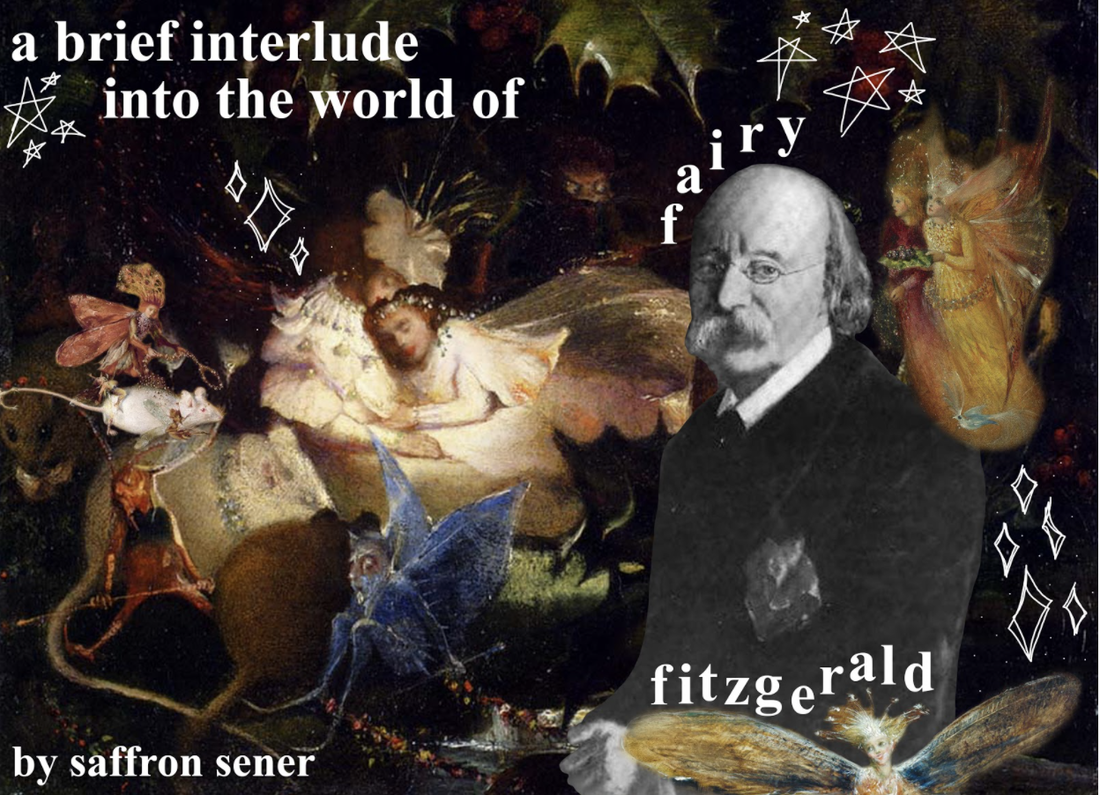

by Saffron Sener If you ask, I will tell you that the focus of my studies in art history is Flemish art. That’s untrue, though, for two reasons: 1) in my time here at UC Berkeley, I have never been able to take a Flemish or Northern Renaissance art course, because, frankly, they aren’t available and 2) my real interest is in weird art. By weird, I mean monsters, little beasts, witches, mythical creatures, allegories, fairies, angels - but mapped onto our world, or early modern perceptions of our world. Think the Bruegels, Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymous Bosch, Francisco Goya, Fra Angelico, John Martin. I don’t necessarily need my art to move me to some great emotional conclusion; I want to be endlessly interested by its strange characters and unique perception of reality, by a glimpse into a world more magical than my own. But I’m not writing this to ruminate on my internal turmoil about my art history concentration. I’m here to talk to you about Fairy Fitzgerald. A 19th century English painter of fairies, dreams, flora, and fauna, John Anster Fitzgerald embodied a very Victorian fascination with magical otherworlds. He became known as “Fairy” Fitzgerald by his contemporaries for his loyalties to the creation of fairy scenes. Strange, elvish creatures fluttering beside miniature peoples dressed in acorns and flowers, commiserating with kittens and baby bats (A Cat Among Fairies), or maybe a rabbit (Rabbit Among the Fairies). Long limbed, sharp winged things scratched across the canvas, fluttering over ocean waves that tumble over each other onto a seaweedy beach (Sea Sprites). The Wounded Squirrel, John Anster Fitzgerald, likely 1860s Works like that above feel like an attempt by Fitzgerald to reckon with the rapid industrialization of his native United Kingdom and the destruction of its natural landscape. We’ve all likely learned of the peppered moth, whose quick evolution from a white and black mottled coloring to a wholly black coloration was due to the intense exponential increase in industrial smoke in 19th century England. This pollution was so severe that soot blanketed the English countryside, enveloping trees so thickly that only the darkest moths could be sufficiently camouflaged and survive. The tangible effects of unfettered, destructive industrialization were growing into themselves during Fitzgerald’s lifetime, and the natural world of this period was much more suffocated, unstable, and under threat than that of a century prior. The Wounded Squirrel depicts a far different human relationship with this world. Humanlike creatures (made more pure by their expansive, colorful insect wings, and humbled by their miniature size) heal an injured squirrel; there is no dominion of one over the other. The background of this piece extends into an untouched, idyllic meadow. There is no soot, no smoke - Fitzgerald utilizes mythical beings to imagine a reality much unlike his own in 1800s London. I attempted to learn about Fitzgerald’s upbringing or artistic background to better understand his great allegiance to the fairy genre. However, I found little information because there is little information to find; his biographers and the few art historical considerations I unearthed about him all agreed on his vague personal life. His birth date is unclear, sometime between 1819 and 1823. He is assumed to be a self-taught artist, but is known to have been exhibited in the Royal Academy of Arts in 1845, when he was likely in his mid-twenties. His father was a generally disliked poet by the name of William Thomas Fitzgerald whose poetry was rooted in English patriotism. Beyond that, though, his early life remains very shrouded. Fairy Hordes Attacking a Bat, John Anster Fitzgerald, 1860s Perhaps one of the more appealing aspects of Fitzgerald’s works to me, though, are their ominous undertones. Fitzgerald’s worlds appear beautiful, tender, enchanted. Yet, they are imperfect, almost sinister at times. Elegant fairy crowds watched over by fiendish things crouched in the canvas’ corner; they are whimsical, otherworldly scenes with an edge of danger creeping ever closer. His dream-related works feature impish creatures, hovering above sleeping subjects as they drift off into slumber (check out The Artist’s Dream for an example). Many tie his works to drugs like opium, a Victorian favorite, and the precariousness of psychedelic trips. Teetering between perfect wonderland and magical ruin, his scenes feign eccentric perfection. Yet, they are delicate fantasies; yes, in Fairy Hordes Attacking a Bat, there is a legion of little fairy people with wonderful flowery outfits and shimmery, iridescent wings. But they’re actively attacking a bat with broken twigs, forcefully pushing the wide-armed animal deeper into the background. What does this mean for Fitzgerald’s world? There is violent conflict - war, even. These scenes are no utopia. Fitzgerald melds the beautified ideal of a fairy - this half-human, half-butterfly thing - with Gothic, dark themes of his surrounding 19th century, of reconciling with the reality of nature being choked out by the grip of industrialization. He is very much a part of a somewhat disillusioned, fanciful movement; think Peter Pan (1902/04), by James Matthew Barrie, or Alice in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll. Whimsical, fantastical, but underpinned by a sense of deep instability and malevolence. Dripping with drug-induced, entranced imagery, tiptoeing between a sensational reality and hellish nightmare. A world that seems extraordinary and its dark, absurd reflection. In my opinion, one of his more captivating pieces is Fairies in a Bird’s Nest. Encapsulating that ever-present tension between the seemingly ideal fairy lifestyle and omnipresent threat of imps and devils, this painting calls upon Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights with its characterization of white, flowery people set against a populated, almost grotesque woodland scene. The body crawling into an eggshell at the bottom middle is a direct citation of the middle panel of Bosch’s triptych, where a crowd of bodies clamber out from a pool of water and into an eggshell. Light shines upon the head of the forwardmost woman in the nest, bathing her and her compatriots in a heavenly luminescence. The creatures encroach on this blissful twig shelter, crawling forward from edges of darkness - as if repelled by the radiance of these women and the flowers that lay across their bodies and nest, they do not enter. Fairies in a Bird’s Nest, John Anster Fitzgerald, 1860 I find, too, that there is a certain ability to map queerness upon this work; the closeness and tenderness of this moment, of these three women sheltering from the devils and imps that abound beyond the limits of their twig nest, feels particularly queer. Maybe I’m projecting my own queer desires (of living in a bird’s nest with my partner, not so much the devils surrounding us), but I do really struggle to believe these little fairy ladies drape themselves across each other and that twig shelter platonically. That’s so much more boring to me than if they were lovers, waiting out the night and the devils that reside within it. If I may really lean into a queer reading of this work - perhaps the devils and imps represent the hate-filled, monstrous perception of “sin” regarding homosexual love, and the soft, safe nest embodies a sort of queer refuge. I have no reason or evidence to believe that this is what Fitzgerald intended. I also understand that he was a man, so tracing a woman-centric queer love narrative onto his work is not particularly realistic. Does it really matter, though? This painting is meaningful in that way for me. Maybe I’m making Fairy Fitzgerald turn over in his grave. But, fairies, sprites, and their magical realm holds so much queer possiblity for me. My housemates and I all agree that Pixie Hollow Online was a communal gay root for us. Fairies in a Bird’s Nest just takes me further down that rabbit hole.*

* Oh, and it has an absolutely amazing twig frame - original to the 19th century. I swoon.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|