|

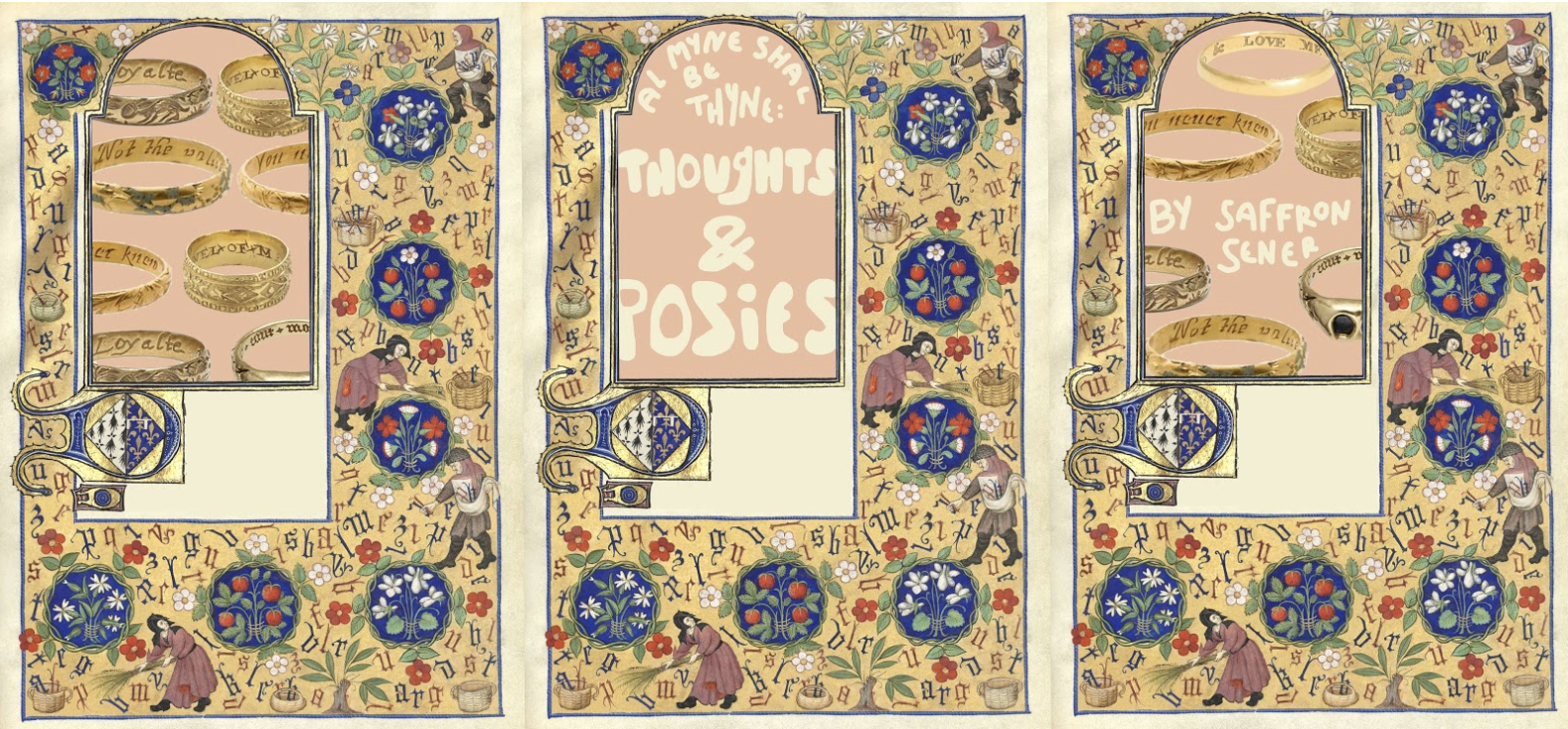

By Saffron Sener At my best, I have between nine and thirteen rings adorning my fingers. This collection has developed since the day I realized that although my mom rebukes the wearing of jewelry, I, as a person separate from her, canin fact wear it anyway. My collection is vast and highly varied; from that which you accumulate from toy dispensers at pizza parlors to my prized $25 opal band, my fingers have worn it all. Although I have amassed hundreds of rings - the horrible ornamental things of my experimental middle school days, my now-refined silver bands and signets - there remains one type of ring I admire the most, yet never have had the pleasure of wearing: a posy ring. A 16th century posy ring, inscribed with “un temps viendra” (exterior) and “mon desir me vaille” (interior). Of course, my greatest impediment to owning a posy ring is the simple fact that they are from a bygone era and place: early modern Western Europe. Sure, I could certainly obtain a modern version - if it were not for the hundreds of dollars that endeavor would cost me. Even more cash, though, if I wanted a genuine medieval relic; on the low end, approximately $2000 would get me a “late medieval gold posy ring”. For those who may not know, a posy ring is a ring (surprise!), often a simple band of gold, inscribed with a posy, or rhyme. The inscription can be on the outside or inside of the ring, though most I have come across boast the more secretive rendition, with the engraved rhyme on the interior of the band. They were a late medieval, early modern phenomenon, most popular from the 15th to 17th centuries in England and France. Though I mainly associate them as being tokens of affection given between lovers, they could also signify gifts of respect or prestige (especially in examples where the rings have been encrusted with a jewel of some sort). There is something about this alliance of text and ring that is endlessly appealing to me. Of course, the ravenous historian in me loves that they’re historical objects I would happily wear now and use (and abuse) as a means to make every conversation about my personal historical interests. But, as a writer, and as someone who has often found a certain poignancy in text that I fail to reach in spoken word, these little posies simply radiate tenderness and passion. You wouldn’t go through all the trouble of inscribing a gold band with a few words of rhyme if you didn’t resonate wholly with those words. Especially when you consider that many rings were inscribed on the interior, and thus were not an immediate or obvious display of wealth; rather, they were a personal message, passed between individuals bound by a golden band gracing one of their fingers. Perhaps they feel so meaningful because their message is hidden, tucked beneath a ring of gold. Or maybe it is the action of those words existing against your skin, directly in contact with your person, your body, pressing against you with no barrier, no boundary. The words are truly yours; they are tangibly connected to you every moment the ring is on your finger. Oh, how I swoon. 17th or 18th century posy ring, inscribed with “Many are the stars I see but in my eye no star like thee.” Beyond the ring’s basic construction, though, are the words. The ring carries with it not just the inherent value as a luxury item, a gift, but the added significance of text. The gifter offers not only an extravagance, but the ultimate romancing: a line of poetry. Like a lock of hair, or a wallet photo, a bit of that person is with you, but even closer - their words meld with your body as something that you wear, perpetually hugging your finger. At a posy ring’s base, the meaning is derived from those words or symbols engraved upon it. Otherwise, it’s just a band. Arthur Humphreys’ 1907 A Garland of Love: A Collection of Posy-Ring Mottoes catalogues an alphabetical list of just what the title says. Some are swoon-worthy, while others feel nonsensical in our modern age. They are just a few words (limited, of course, by the size of the band), yet feel so personal, so purposeful. I have collected a few of my favorites below:

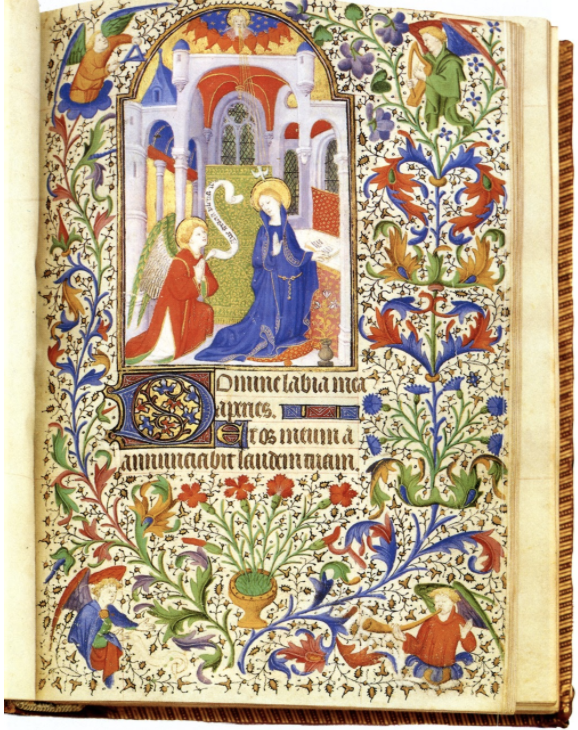

On a broader note, I admire the medieval tradition of integrating text and art. The concept of merging word and visual culture or art is typical of the early modern Western world. You can see it in paintings, as well; Fra Angelico’s 1450s Armadio degli Argenti, a set of nine panels depicting Jesus’ life, is bordered by Latin text explaining the corresponding scene of each panel. Illuminated manuscripts exemplify the ultimate medieval combination of text and image. In a more playful way, Jan van Eyck signs “Johannes de eyck fuit hic,” or “Jan van Eyck was here, 1434,” on the wall of his Arnolfini Portrait. A page from a French illuminated manuscript, the Book of Hours, dating to 1410. Notice not only the words below the illustration of the Annunciation, but the strip of text within the image as well. And, of course, the beautiful, colorful natural decoration filling the page! Considering its era, the inclusion of text proclaims something unattainable to most: literacy. The ability to read in your vernacular, be that English or French (although there is the occasional Latin inscription) was reserved for certain classes - those who could afford education and those who were educated by the church. With the innovation of the printing press in the 15th century, the accessibility of text as a mode of communication between the greater populus of Western Europe certainly expanded. But was the common farmer or barkeep reading through publication upon publication to locate the perfect line for their sweetheart? Likely not. Even more unlikely when considering the cost of gold and the expense of inscribing it. So, this was a fashion of the rich - unsurprisingly, and somewhat disappointingly. I want so badly to imagine two commoners in the English countryside, dressed in bonnets and tunics, sneaking about and sharing their secret affections tucked away behind the bands on their fingers. I want to think of them romancing each other by candlelight, creating poetry out of their love and feeling the need to capture it in the valleys of a ring’s engraving. Of course, this idyllic image is shattered when I remember their sense of hygiene, or lack thereof, and what it would be like to be a commoner or a woman or generally a person in 15th century England. The magic of the posy ring remains, though. What would I want on the posy ring I’d give to my partner? You set my heart ablaze, forever and always. A 17th century posy ring, engraved with “trew love is my desyre.”

1 Comment

|

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|