|

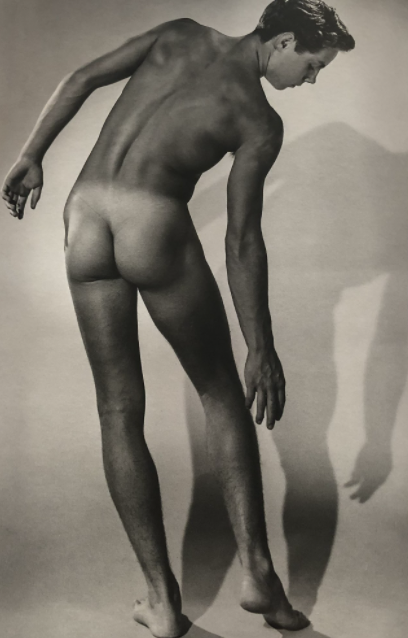

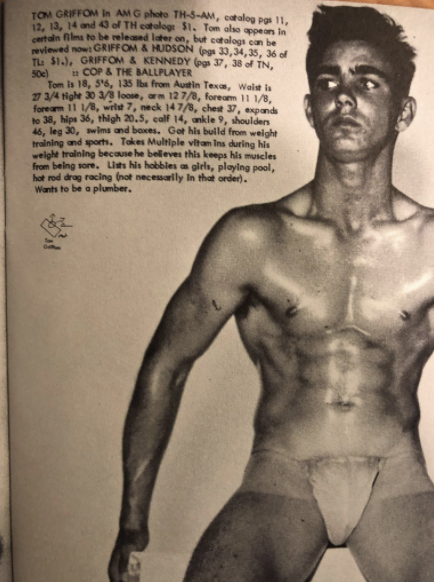

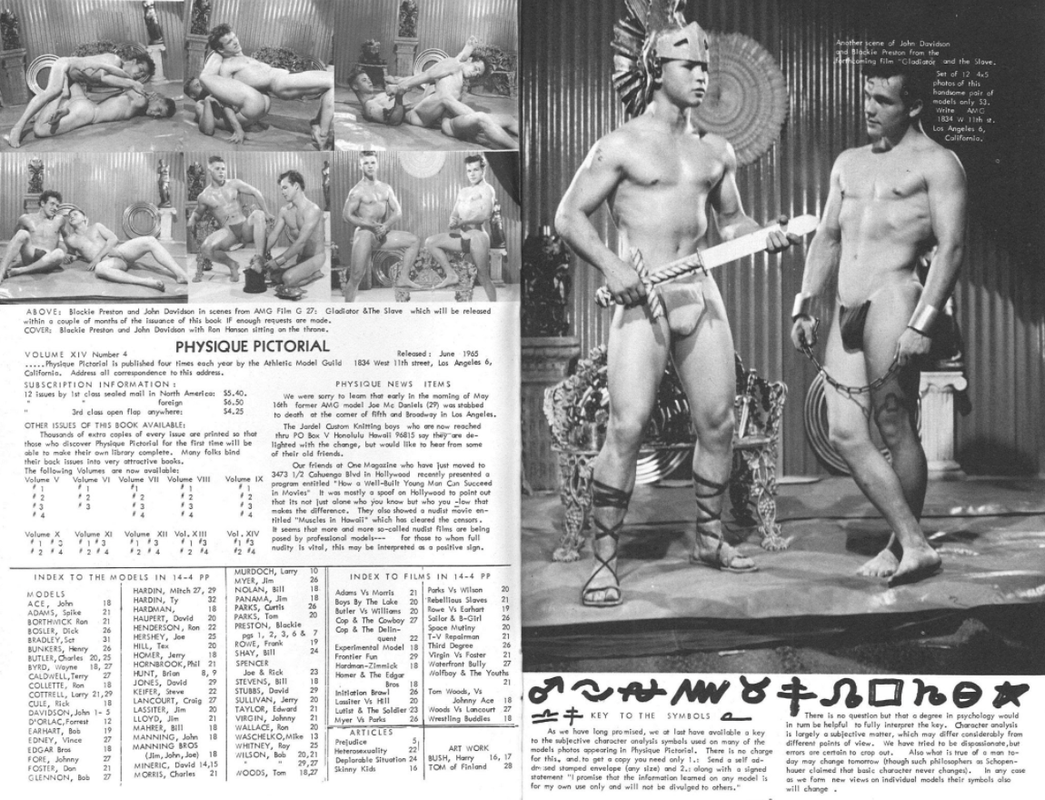

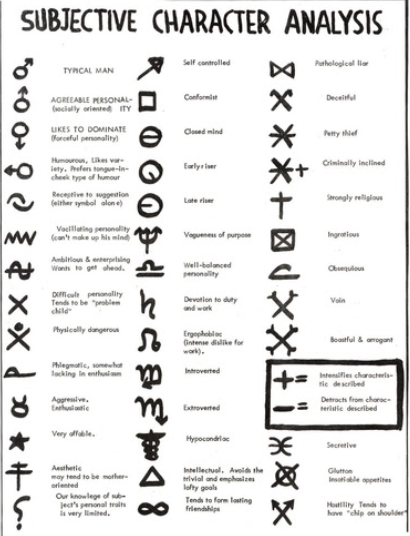

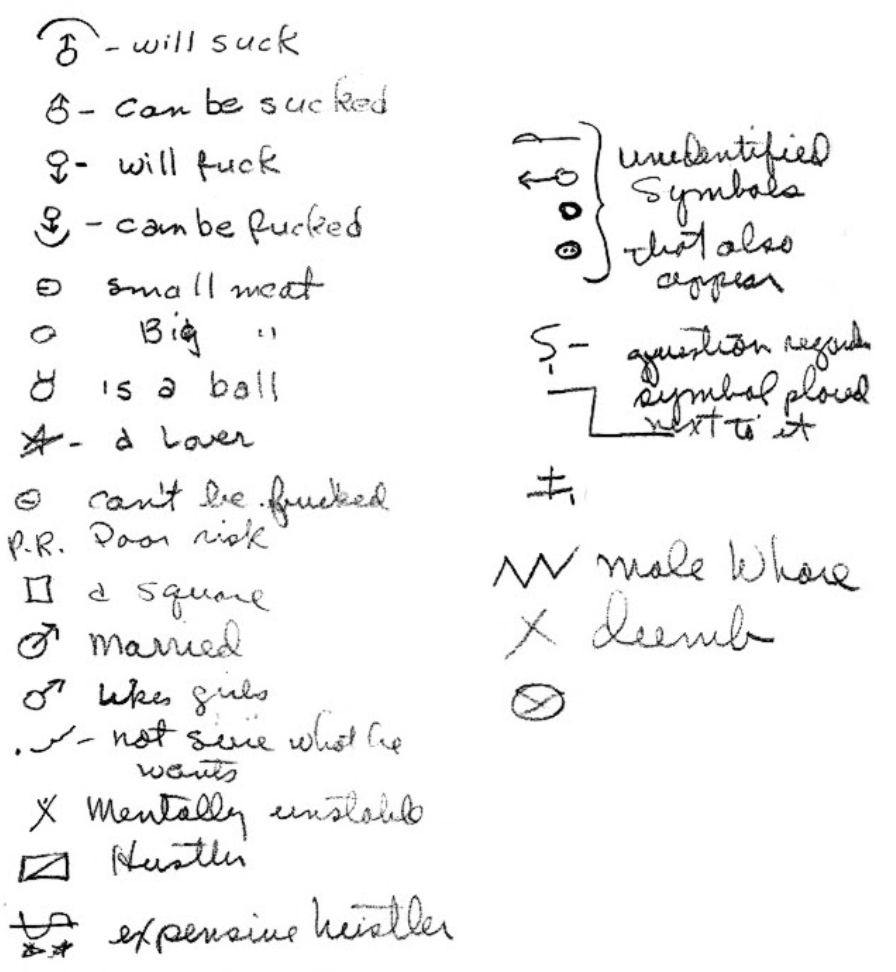

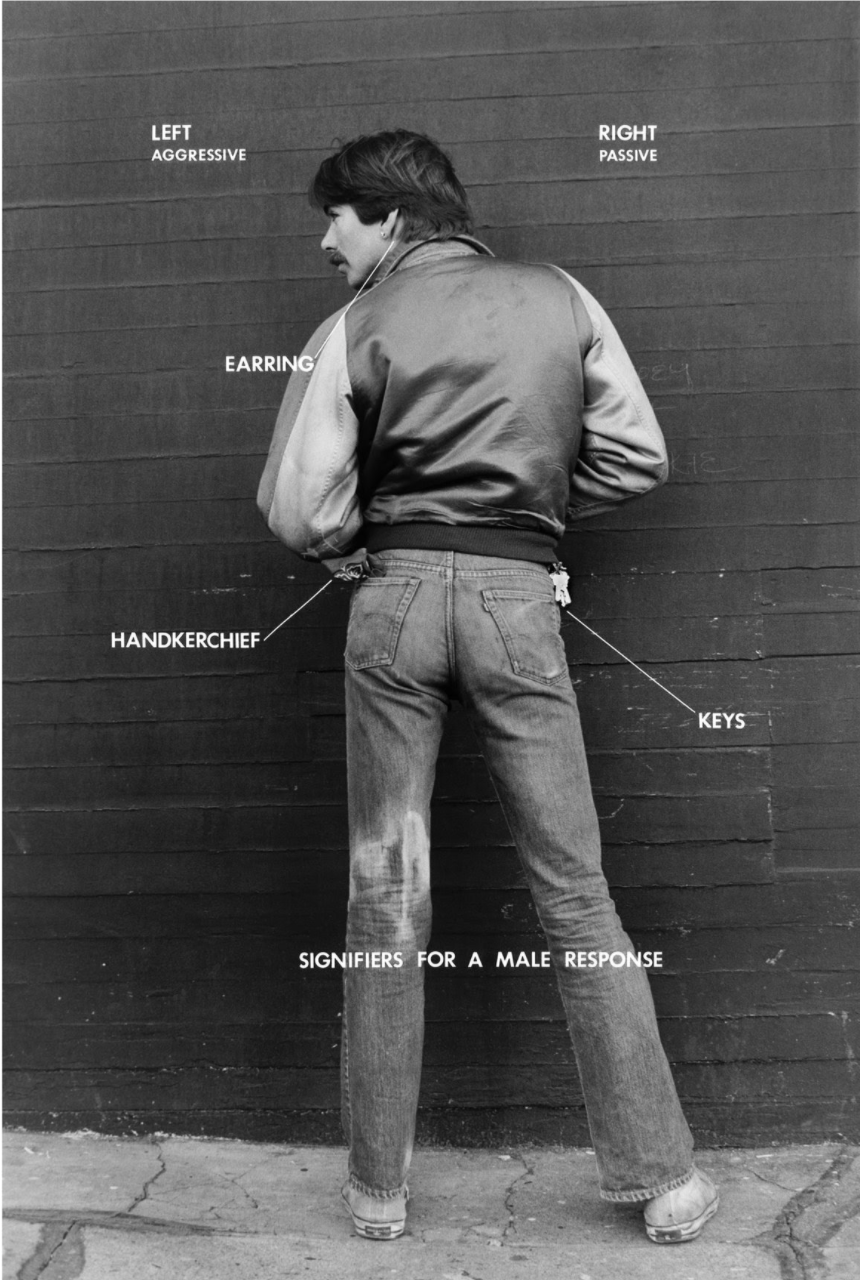

by Maxwell Sutter Zinkievich Prior to the second World War, the prevalence and structure of homosexual society within the United States was fundamentally fragmented and unrecognized. Homosexual culture indeed existed in the United States, but there was yet to be an overarching lexicon to tie together gay individuals into a solid subculture. During the war, however, havens of gay male culture began to recognize themselves through what is suspected to be a symptom of the famous “Blue Discharge” and the resulting unshipping of gay men from the Navy at bases such as San Fransisco’s Presidio. While these people were still ostracized from mainstream society, they found community and culture within each other. The city of San Francisco quickly became a hub for queer culture and gained notoriety for these groups even faster. The increased prevalence and activity of queer people caused a push to describe their behaviors. Alfred Kinsey, inspired by questions raised by earlier German studies conducted by Magnus Hirschfeld at the Institute of Sexology in Berlin in the 1930’s, was one of the first to begin a mission to map, describe, and taxonomize the sexual behaviors of humans. At the same time, artists like Robert Mizer and Hal Fischer were working within the homosexual community and making observations and recordings of their own. While medical researchers like Alfred Kinsey were fascinated with physical behaviors, they found it hard to collect meaningful data on the personal lives of the individuals that they surveyed. Bob Mizer’s Subjective Character Analysis, Hal Fischer’s Gay Semiotics, and other taxanometric descriptions of queer individuals served the gay community not only as recordings but also tools of teaching and indoctrination into a subculture comprised of individuals ostracized from mainstream society. They create a distinct visual language for those privy to the code to glean information about others like themselves. While Kinsey’s work demonstrates the mainstream interest in gay culture, analogstandings, and identities. When Alfred Kinsey founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University in 1947, the college’s mission was to document and describe the sexual behaviors of the human species. Using a combination of clinical trials as well as extensive surveying, he was able to collect a truly astounding amount of quantitative data describing human sexuality. His analytical findings were first published in Sexual Behavior of the Human Male (1948). In this work, Kinsey and fellow researchers focused solely on the “human male,” using survey data on thousands of men’s sexual experiences. While Kinsey considers a wide breadth of male sexuality, for the objectives of this paper a focus will be placed on section twenty-one entitled “Homosexual Outlet.” Within this section, Kinsey generally discusses two things: what percent of the human male population is or considers themselves homosexual, and what behaviors and attitudes make a man a ‘homosexual.’ Through his surveys of thousands of men, Kinsey was able to collect a complete view of what the sexual landscape looked like for men at the time. He was able to find that a sizable proportion of the population had had at least one encounter that could be deemed homosexual in their lives. Pardoxically, Kinsey also finds that the vast majority of the human male population would not describe themselves as homosexual, even if these individuals conducted sexual relations with other men on a somewhat regular basis. “. . . the homosexuality of certain relationships between individuals of the same sex may be denied . . . because the situation does not fulfill other criteria that they think should be attached to the definition. Mutual masterbation between two males may be dismissed . . . as not homosexual, because oral or anal relations [did not take place]. . . Some males who are being regularly fellated by other males without, however, ever preforming fellation themselves, may insist that they are exclusively heterosexual.” (Kinsey, pp. 616, para. 2-3) Kinsey makes these remarks in order to further clarify the fact that not only is the world of sexuality not as logical and straightforward as a clinician would hope, but also that there is not even a lot of consistency in individuals’ claims about themselves. The argument could be made that this is due to the fact that Kinsey’s surveys were voluntary but also that societal opinions of homosexuals were particularly sour at the time. This explains Kinsey’s adoption of an analytical gaze and his primary interest purely in the quantitative data on homosexual experiences. Through the study, Kinsey focuses on behaviors themselves and the implications they have on sexuality and sexual identity, while somewhat ignoring the greater societal and cultural pressures that someone identifying as a homosexual would have to bear. As per its title, Kinsey’s work highlights the physical sexual behaviors of the human male. I am distracted, however, by the lack of inclusion for the political and societal implications that would have pressured these individuals at the time of the study. While Kinsey discusses these pressures, and understands the non-response bias, he does not seek to explore cultural forces within the homosexual community. This was a culture that Kinsey did not have access to, and did not speak the language of. Moreover, Kinsey as a researcher was not privy to the inner lives of persons living outside of conventional heterosexual society. In order to get a perspective into the everyday lives of homosexual men in the mid 1900s, one must look to publications made by, and for, self-proclaimed homosexual individuals. Fig. 1 - 1000 Model Directory (VARIA), Bob Mizer, Jim Grant, Silver Gelatin Print, Los Angeles, California, 1949 Robert “Bob” Mizer was an American homoerotic photographer famous for his self-published magazine Physique Pictorial. In 1945, Mizer founded his Los Angeles photography studio -- the “Athletic Models Guild” or AMG. . Mizer’s publications were sold under the guise that they were bodybuilding magazines, not for homosexual desire, but heterosexual appreciation of another man’s physique. It is quite obvious, however, to both a contemporary and modern viewer that these photographs carried intentional homoerotic undertones [Fig. 1]. Issues of Physique Pictorial typically included photographs of models, a brief synopsis of their body measurements, a few sentences about their interests and life plans, and information about what to mail to Mizer in order to receive films or other media of them alongside other models (usually wrestling or some equally suggestive activity). In the October 1964 issue, Mizer began to include cryptic hand-drawn symbols that appeared alongside the text descriptions of models. These symbols appeared to be composites of several unique smaller symbols, and the combinations varied widely between different models [Fig. 2]. These symbols appeared in conjunction with model photographs without apparent explanation for the better part of a year until the publication of Volume 14, Number 4 in June 1965. The first two pages [Fig. 3] provide the reader with not only an explanation of what these symbols represent, but also how to decipher them. Mizer uses these symbols, which he dubbed his “Subjective Character Analysis” (SCA) to describe not only the personality characteristics of the men that he photographed, but also their sexual preferences and experiences. In the June 1965 issue, in order for readers to gain access to the code sheet, or “key”, for these symbols Mizer instructs readers to: “. . . to get a copy [of the decoding sheet] you need only 1.: Send a self addressed stamped envelope (any size) [to the same address that one writes to purchase films and issues] and 2.: along with a signed statement ‘I promise that the information learned on any model is for my own use and will not be divulged to others.’ ” (Fig. 3 pp. 3 para. 1) In conjunction with the complicated procedure which contains a pseudo-NDA, it is clearly evident that the level of secrecy surrounding the nature of this publication was based in mainstream perceptions of homosexuals. Fig. 2 - Bob Mizer, Tom Griffon, Physique Pictorial Volume 14, Number 1, section of page 13, section showing Biography as well as SCA symbol below, Black and White Print, Los Angeles, California, July 1964. Mizer was constantly plagued by lawsuits over the perceived deviance of his photography, and he was required to take various precautions in order to safeguard his work for both his own livelihood as well as for the sake of his customers. Requiring readers to write in through personal mail correspondence was something that was imperative due to the secretive circumstances. However, even if a customer wrote in to receive one of these decoding sheets [Fig. 4], they would only receive a partial decoding of the symbols, which purposely omits sexual descriptions and stays firmly put in personality characteristics. Mizer himself would only send out a hand-written portion including the sexual interests and histories of his models [Fig. 5] if he deemed the reader to be trustworthy enough. This usually meant that they both expressed homosexual interest as well as were long-term subscribers to the magazine. The goal of these SCA symbols was never explained in length by Mizer other than to say that: “There is no question that a degree in psychology would in turn be helpful to fully interpret the key. Character analysis is largely a subjective matter, which may differ considerably from different points of view. We have tried to be dispassionate, but errors are certain to crop out. Also what is true of a man today may change tomorrow (though such philosophers as Schopenhaure claimed that basic character never changes). In any case as we form new views on individual models their symbols also will change.” (Fig. 3 pp. 3 para. 2) Here Mizer is keen to tell the reader not only that these symbols are not definitive, but only serve to offer a momentary view into the life of the models. This arguably has two readings, one to the reader who would receive the non-sexual key and the one that received both. Perhaps Mizer is speaking to the sexual fluidity that he and his models would be aware of within the homosexual community which Kinsey only analytically describes. To those with the sexual key, Mizer could have been hinting to the idea that many of the models may have been more open to homosexual encounters than they actually were, in order to increase the erotic appeal of the magazines. Fig. 3 - Physique Pictorial Volume 14, Number 4, Pages 2-3, Bob Mizer, “Films Advertisement and Key to the Symbols”, Los Angeles, California, June 1965. (Scan Courtesy of PhD Candidate Max Böhner at the Humboldt University of Berlin) Fig. 4 - Bob Mizer, Subjective Character Analysis Decoding “Key”, Los Angeles, California, circa 1965. Reproduced in Dian Hanson, Bob’s World (Cologne: Taschen, 2009), p.11. Fig. 5 - Unknown, Reproduction of Bob Mizer’s Sexual Decoding of his Subjective Character Analysis Lexicon, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California, circa 1965 https://moca.tumblr.com/post/73314240458/thenumberonesolitarycyclist-bob-mizer-marked While Mizer’s Subjective Character Analysis speaks to the physical actions of individuals just as Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male does, they both ignore the subject matter of Hal Fischer’s 1977 photographic exhibition Gay Semiotics. Within this photographic body, Fischer ignores the behavioral and the sexually mechanical. Instead he focuses primarily on the semiotics of gay culture: elements of fashion and behavior that would signify a broadcast of homosexual desire to others. Fischer was particularly interested in elements of fashion that signified homosexual position and standing. Using diagrammatic photographs paired with textual explanations, Fischer attempts to give the viewer a typical specimen of a gay man. In his photograph Signifiers for a Male Response [Fig. 6] Fischer shows the viewer several typical tropes of homosexual street fashion in San Fransisco. Throughout the rest of Gay Semiotics, Fischer continues this diagramatic approach to describing his own culture. Fischer discusses elements that would be viewed as alien to heterosexual culture, such as early elements we would now call “flagging,” intersections of the homosexual and S&M scene, as well as the prevalence of Amyl Nitrate, as an integral part of the community’s sexual activities. This is not only for the artistic purpose of exposing the inner workings of a subculture, but also to act as a historical recording and teaching tool for future generations of gay men. Fig. 6 - Hal Fischer, Signifiers of a Male Response, San Francisco, California, circa 1977 The behavior and classification of homosexuality dominated Kinsey’s exploration on male homosexual tendancies. Kinsey was only able to get a glimpse into their world through the use of his surveys where he asked questions based on their own personal experiences with other men. However, what Kinsey failed to find important is the culture that surrounded that group of people. And while it may have been seen as outside of the scope of his work, it would have answered a lot of his questions. As Kinsey discovered, sexuality is something that is neither static nor binary. Bob Mizer’s Subjective Character Analysis concurs with Kinsey by pointing out that both the personality attributes and sexual preferences of his models were also in flux. In addition, Mizer acknowledges that his SCA was at best recorded by an amateur, with a much smaller sample group than Kinsey, but they nonetheless reached similar conclusions. The sexual behaviors of homosexual, queer, and straight men are not only constantly changing in theirfocuses, but also in their drives. Kinsey struggles to define men, Mizer seeks to describe them, and Fischer taxonomizes typical expressions of homosexuality on the streets of San Fransisco. Each of these men seek to describe homosexual culture and they each have a unique approach. However, within the gains and losses of each we do get a glimpse into the greater, and paradoxically more intimate, world of what living as a gay man in the middle of the 20th century would have looked like. Bibliography

Kinsey, Alfred C., et al. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Indiana University Press, 2010. Lord, Catherine, and Richard Meyer. Art and Queer Culture. Phaidon, 2013. Mizer, Robert "Bob". “Subjective Character Analysis Key Advertisement.” Physique Pictorial, June 1965, pp. 2–3. Stacey. “Beyond the Muscle.” East of Borneo, 2 Nov. 2016, eastofborneo.org/articles/beyond-the-muscle/.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2024

Writers

All

|