|

by Lucas Fink Rick Altman wrote about how Hollywood narrative cinema is basically structured around and propelled by a character with easily-understood motivations progressing through a series of events chained together causally. So, things like spectacle and pathos (musical numbers, action scenes, sobbing, screaming, bright colors, etcetera) are outside, are in excess of, this dominant Hollywood system. Altman offers a crucial nuance here, though: this excess is only conceived of as such relative to the system that asserts itself as dominant. The implications are that excess, secondary logics, minor positions, spaces of subversion, or whatever you want to call them are not in themselves excessive. In his words, “Unless we recognize the possibility that excess – defined as such because of its refusal to adhere to a system – may itself be organized as a system, then we will hear only the official language and forever miss the text’s dialect, and dialectic”(35).The rub here is that, if given the chance, that which is repressed by a given dominant system could very well organize itself into its own system. I wish ask if this has ever actually happened, if oppositional elements have ever been allowed to flower into a system of their own. The song “Brother Sport” by psychedelic pop group Animal Collective presents, I think, a decent approximation of such a system, a system in which the marginal becomes the dominant. The dominant’s status as such, then, is a product of contingency, and forever precarious. First, we must define the dominant for pop music. Altman here is working with film, and thus defines the dominant for film: “With few exceptions they[film theorists of the past two decades] have stressed omniscient narration, linear presentation, character-centered causality, and psychological motivation … [as well as] the importance of invisible editing, verisimilitude of space, and various devices used to assure continuity”(15). It is in reference to these dominant standards of storytelling that Altman identifies the excessive: contingency/coincidences(33), parallelism/multiplicity of perspectives(20-26), overlong spectacles, and unabashed pathos. What, then, constitutes the dominant for contemporary pop music? We can, with little research effort, determine that the vast majority of popular music adheres to the “verse A – chorus - verse B – chorus – bridge - chorus” structure, or some mild variation. It is now apparent why pop music is often said to be “hook reliant”, for the dominant structure is designed to foreground a singular catchy refrain. Everything that is not the hook/chorus then takes on a supportive role, becoming connective tissue which justifies the song’s existence as a song - as more than just one random earworm - usually via the delivery of some narrative related to the chorus’s lyrical content. Pop’s lyrical content is impressively diverse, making it difficult to explain the genre’s dominant in terms of lyrics. Whatever the song is “about” superficially, though, the lyrics almost always situate the listener comfortably in either a physical setting, interpersonal scenario, or psychological condition. Importantly, because of pop’s unswerving loyalty to its central refrain, the situation the listener finds themselves in is usually static; a given song is obligated by its structure to repeat its one refrain, and whatever lyrical content therein, multiple times. Charli XCX’s “Vroom Vroom” is about driving really fast; the listener begins the song in a fast car and ends the song in a fast car. Lorde’s “Royals” is about class resentment; the listener begins the song simultaneously fetishizing and repudiating inaccessible opulence and ends the song doing the same thing. However, just as Altman discusses the necessary presence of a counter-logic wherever there is a dominant logic(31), so too is the marginal present in pop. The verses, being the only non-repeated element of pop songs, are the marginal. More specifically, the verses’ promise of change, of a meaningful evolution throughout the song, is the marginal, even though this is a false promise. The verses exist to trick the listener into thinking the end of the song will be different from the beginning, just as unpredictable beginnings in American film exist to veil the fact that the ending will almost certainly be a happy one(Altman 32). How does “Brother Sport” systematize elements that would otherwise be subordinate/tertiary? The track engages in a wholesale jettisoning of classic pop structure such that it becomes impossible to even locate a verse or chorus. Instead, the listener encounters three rhythmically distinct hooks woven into a lush soundscape of twinkling synths and thrumming African/Latin-inspired percussion. The second hook immediately follows the first, and the last hook is separated from the others by an unapologetically lengthy chunk of instrumental phantasmagoria. The rub here is that each hook – which, in the context of a classic pop structure, would be the centerpiece of its own singular song - is mercilessly excised from the track to make room for the next. The primacy of hooks/the revered status hooks enjoy in classic pop song structure is thus wholly undermined, indeed flatly rejected in favor of an entirely different system, an entirely different operationalization of hooks. “Brother Sport” then organizes itself not around the singular, imitable, omnipotent God-Chorus, but around a rhizomatic multiplicity of catchy lyrical nuggets, none of which are afforded more ontological significance than the others. Furthermore, Animal Collective supplants the illusion of progression common to classic pop tracks by actual progression. In “Brother Sport”, the situation is an interpersonal scenario: the singer, whose father has just died, is giving his brother advice regarding mourning. Here’s the icing on the cake, though: the song, in virtue of its atypical structure, ends differently than it began, for the writers have the gall to conclude with a hook other than the one they began with. We begin with refusal of tragedy(“I know it sucks that daddy’s done but try to think of what you want”) and end with hopeful, future-oriented euphoria(“You’ve got a real good shot […] Keep it real; give a real shout out”). “Brother Sport” then affirms that, however naturalized the classical system may be, its position as such is perpetually tenuous and contingent on the subduing of its excess, excess which contains a world in itself, albeit unactualized. “Brother Sport” is this actualization of the worlds nestled in the crevices in the status quo.

0 Comments

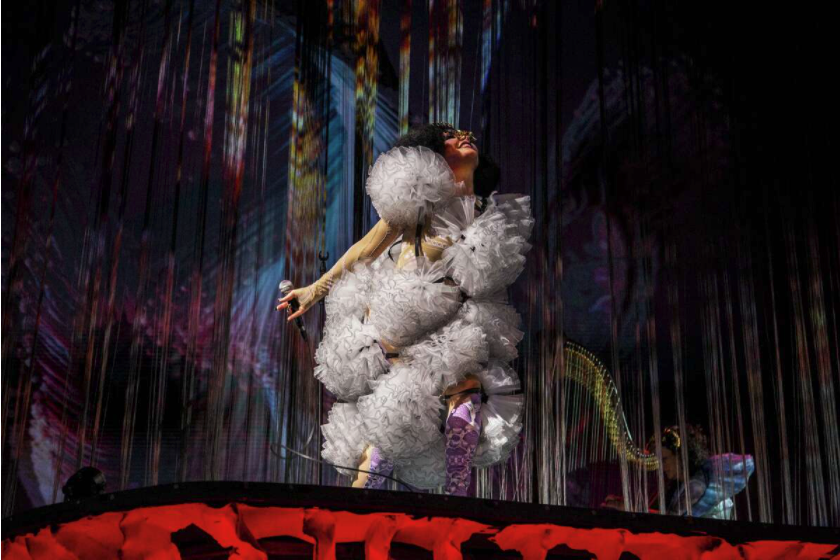

by Maxwell S. Zinkievich When I received my first car at sixteen and I got into the driver’s seat for the first time, my parents had already placed CDs of Björk’s studio albums Vespertine and Post in the center console. From a young age I had been attracted to her unique and powerfully realized personal drive to create and to innovate. Each album that she releases, each project that she works on, is distinctly of her own; unreproducable. I listened to her music in almost a religious sense, and before the 15th of February this year, I had yet to see her in concert. I will say very little to criticize Björk and the production of this show within this “review” of sorts; I hope that it be taken more as a discriptive account of what this queer kid experienced rather than something that one would see in Rolling Stone. While this show has received critical acclaim from a myriad of critics (Rolling Stone included) with decades more experience and credibility than myself,, I will do my best not to parrot what has already been said before; even if my opinions mirror theirs closely. In short, the production that I saw on the 15th of February 2022 held at the newly constructed Chase Center in San Francisco is a triumph not only for the production staff, show director, and accompanying musicians, but also for Björk herself. View of the set pieces and projector curtains. source: Santiago Felipe via https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/music/story/2022-01-25/bjork-cornucopia-tour-pandemic I would like to begin by examining the air that was created as the crowd entered the stadium. A floral graphic was projected on the curtain of the stage, throwing off great amounts of teal and pink light into the surrounding stands. As people gathered and found their seats, the atmosphere was unlike anything I had experienced before. People dressed up to attend this event, but not in the manner that one would expect. Sure, there was a fraction that dressed in festival wear or another light-show techno ready attire, there was even a swan dress or two. The majority of the people in attendance, however, were in formalwear. Not many suits and gowns, but that distinctly SF/Tech world of spiffy clean haircuts and slick gray shirts and pants, maybe a slightly unconventional blazer thrown in for color. Nothing insane, but a step up from the usual uniform of All-Birds and Patagonia. These people were dressing up for something, something more than a concert or live performance. They were there to witness something between the lines of performance art and a symphony—and if anything, they were underdressed. The show opens with an acapella performance from the Icelandic Hamrahlid Choir that set the mood and moment for what would take place after. Their vocals would be used onstage to back up Björk throughout the show, and play a critical part in building the soundscape. After this performance, the stage goes dark and the curtain reveals itself through movement to be a number of sheer and semi-transparent sheets placed at varying depths into the stage. These sheets would be used to catch projections that blended the digital space created by the show's technal art team. The curtains would be pulled in and out of their nooks on the sides of the stage for each track, finding a place where they perfectly work within the stage visuals and the music to build a cohesive and natural extension of the world that Björk was building onstage. Because of this digital canopy, the stage itself was fairly devoid of non-functional set pieces. A tiered system of fungi-looking platforms allowed for staging of the static musicians as well as a dance platform for the accompanying flute ensemble. source: Santiago Felipe/Getty Images for ABA via https://www.sfgate.com/characters_clone_20628_20210818162542/article/bjork-sf-cornucopia-concert-review-16836327.php Here I believe that it is important to make note of the album that Björk is primarily drawing from for the setlist of this production, Utopia. As always, Björk trends to more abstracted and unearthly lyrics and methods of composition. She almost never utilizes a chorus in her work, and breaks away from musical tropes that would make her music repetitive. Her compositions always trend more along the lines of a story or abstract emotional ballad. Utopia is, for many, a pinnacle of this style of work. I would make the argument that none of the songs that Björk plays throughout this show could be termed “danceable”. Not that she is unable to create songs that are, but that the goals that she has as an artist do not fall within the realm of making the next big hit. Therefore, if the reader were to find any recordings of this performance online, I would urge them to watch under the guise of an opera-goer. The production of the show is designed to create an immersive world that the viewer is allowed a glimpse into. One that does not exist outside of the temporal and physical space of the stage. Elaborate costumes grace the bodies of Björk and her accompanying floutists. Fashion houses Balmain and Iris Van Herpen designed the costumes of Björk herself, with elaborate face-embellishments designed by James Merry and make-up by Johannes J. Jaruraak (@isshehungry). source: Santiago Felipe/Getty Images for ABA via https://consequence.net/2022/01/bjork-cornucopia-recap-los-angeles-shrine-auditorium/ I mentioned previously that Björk is an artist who is constantly on the cutting edge of what can be done technologically for her music. She was one of the first artists to include electronic instruments alongside an orchestral arrangement on stage in the mid 1990s and has continued to push the envelope in as many ways as she can. I also mentioned that she has very few non-functional set pieces with her on stage. What she does include that for me falls into the category of functional is a reverberation chamber that was specially constructed for her voice. This physical chamber is situated in the back of stage right and adds a unique flavor to the singer’s voice for certain tracks. She also includes an instrument that she calls “water drums” which take the form of large wooden bowls and a tub of water. The player places the bowls face down in the water and beats on the convex side of the bowl. This creates a uniquely full and reverberating drum sound that is picked up with an array of microphones around the water basin. Some of her tracks require the sound of falling or dripping water which are also captured live from this apparatus. Perhaps the most unique piece of instrumentation that was constructed for this show is what I term an “orbital flute” which is a series of four or five individual silver flutes that have been connected and bent into a circular shape. This instrument stays suspended high above the stage and is lowered around Björk. Thus, when the accompanying flutists play the instrument, her vocals are emanating from a literal encirclement of vibrating, musical air. It is difficult to draw any conclusions about the experience that can be drawn out into the realm or reality. The metaphors of the album Utopia circle around creating a world that is free from a past of hate, anger and pollution. Before the encore, a recorded speech by climate activist Greta Thunburg is played to give the audience the state of emergency that the world is currently facing due to the climate crisis. Perhaps it was Björk’s goal to create a window into a world that is unbounded by these issues and to show the audience the unfathomable beauty and emotional expanses that can be seen if we band together in love to fight climate change. In closing, the show itself was transcendent of the physical world that we inhabit and is a triumph of creative thought and execution. Uniquely visionary, confusing, fascinating, creative, captivating, alien. Uniquely Björk. Björk in Balmain and surrounded by “orbital flute”.

source: New York City Photography/Santiago Felipe via https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/44409/1/bjork-cornucopia-the-shed-new-york-interview Situated along Emilia-Romagna’s eastern shores, the town of Rimini draws huge summer crowds eager to populate the modest coastal town’s seaside promenades and capacious beaches. Villas and resorts erected to accommodate the seasonal swell of imported beachgoers occupy the skylines that lie both to the north and south. But the summertime, and the profitable reverie that the city hosts, must come to an end. Who, or what, remains during the hibernal months that lock the sea under gray horizons?

Unbeknownst to many of its summer inhabitants, Rimini was the birthplace of Italy’s most celebrated director, the larger-than-life Federico Fellini, whose prolific career earned him international acclaim. His slice-of-life realism articulated incisive critiques of Post-War Italy’s social conditions, and the grandiose forays into the phantasmagorical and carnivalesque that defined the latter half of his oeuvre captured the circulating values, desires, and collective fictions of the Italian imagination. In the off-months, the legacy of Fellini has made the town of Rimini a coveted destination among devoted admirers who seek to understand the landscape that produced such a beautifully singular and singularly beautiful artist. With the support of Emilia-Romagna’s Ministry of Culture, Rimini has mobilized a considerable amount of money and effort to monumentalize Fellini and his work, much in the same vein as Bergman’s Fårö or Elvis’ Graceland. The recently inaugurated Federico Fellini Park skirts the sandy edges of Rimini’s northern beaches, a statue casts a shadow of Fellini’s likeness during the right time of day along the Marecchia, and throughout the town bakeries hotels and cafes all bear the namesake of the now deceased maestro. His ghost permeates and reinscribes the town itself: the beaches bear an uncanny resemblance to the seaside abode where we first meet Gelsomina in La Strada, the gloomy mist that drapes over the water in the late evening is indistinguishable from the blanketing fogs of Amarcord and I Vitelloni, and so on. But the implication of Fellini does not suffice. Surely one of cinema’s greatest contributors and pioneers is deserving of a more ceremonious commemoration. The most appropriate elegy is of course the viewing of the filmography itself. But such an undertaking cannot be demanded of the weekend sightseers who, perhaps unfamiliar with Fellini and his work, may require some inertial nudge. Furthermore, there is a rapacity among those who are familiar with Fellini to cultivate a deeper understanding of the spiritual and cultural underpinnings of Fellini’s life that were in turn prismatically refracted through his films. But how does one represent the animus of such a resonant and epiphanic body of work or the life of their enigmatic creator? The opening of the Fellini Museum in August of 2021 is the latest and boldest attempt to do so. The Fellini Museum is not a single location but is instead an entire environment dispersed across several buildings and public spaces. The 15th century Castel Sismondo has been reoutfitted as an interactive and immersive exhibit that functions as a cinematic cornucopia containing fifteen rooms that each engage with different dimensions of Fellini, his films, and his legacy. It is undoubtedly the centerpiece of the Fellini Museum. La Piazza dei Sogni (Plaza of Dreams), shrouded in a fog meant to recall the transatlantic voyage of Amarcord, is bordered by a veil of water that reflects the edifice of Castel Sismondo and Teatro Amintore Galli. Further along the plaza is a 17m golden, illuminated circular bench reminiscent of the circus rings at the end of 8½, a convivial public space that, much like the film, celebrates a communal solidarity and equanimity. One can stroll from Castel Sismondo across the Piazza dei Sogni to the other major indoor exhibition space, Palazzo del Fulgor, along a pathway of sound that weaves voices and music contained within (and inspired by) the films of Fellini. Palazzo del Fulgor is a historic movie theater immortalized in the film Amarcord but more importantly was the theater Fellini himself attended in his youth. It has recently been restored and screens a rotation of Fellini’s filmography as well as other contemporary releases. Palazzo del Fulgor is the most recent addition to the Fellini Museum, utilizing three floors to conjure a perennial interpretation of Fellini, locating his legacy fits in the wider landscape of film art. Next to the entrance of the Palazza is a jesmonite statue of a rhinoceros on a small boat, a reference to the film E La Nave Va and the main symbol of the Fellini Museum. The exhibitions in Castel Sismondo employ material installation pieces, projectors that fill the walls with various video excerpts, and text elements that help contextualize the spaces. Immersive soundscapes cohere the disparate elements and gestalt in a multimedia and multisensory exploration of Fellini. The contents of the fifteen rooms are as follows:

Palazzo del Fulgor’s exhibits provide contemporary reflections on Fellini, and more abstract ruminations on the significance of his films. The Cinemino is a small theater programmed with interviews with celebrated directors and film scholars that reinterpret his themes on diegetic, critical, and discursive levels, as well as other vignettes that frame the scope and magnitude of Fellini’s career. The Room of Words is a soundproof standing space with overhead speakers that project the voice of Fellini contemplating himself and his work. This abstract exhibit interlaces several audio excerpts of Fellini grappling with the meaning of his life and the significance of his efforts as a filmmaker. The House of the Magician reveals the mystical aspects of Fellini’s work, and his propensity to expand his poetic range through studies of esoteric, occultist, and mythic texts. The Moviole allows its attendees to inter-splice and remontage excerpts of Fellini films, underscoring the continuity of his craft across several decades. Attendees also have the opportunity to explore the museum’s repertoire of letters, posters, testimonies, and drawings of Fellini via the digital archives. The Fellini Museum beckons its visitors to enmesh themselves within the inestimable work of Federico Fellini and recognize that these films have unraveled the antinomies of our reality. These works bridge the divides between realism and fantasy, between the sacred and the profane, and between tradition and contemporaneity. As such, Fellini, and this magisterial space crafted to celebrate him, proffer more than intellectual or spectatorial stimulation, rather, an apprenticeship to finding one’s lust for life. by Truly Edison, Lucas Fink, Lucas Wylie, and Phil Segal PART 1: Truly on the Troubling Deficit of Horniness in Modern Film

Half an hour before I watched Denis Villenueve’s Dune on Friday, I reread one of my all-time favorite pieces of film meta: Raquel S. Benedict’s “Everyone Is Beautiful And No One Is Horny”. I honestly can’t recommend this article enough to anybody interested in film culture, but I’ll give the basic rundown. Benedict identifies the human body as “a strange contradiction at the heart of the modern blockbuster”, impossibly gorgeous while simultaneously depicted as devoid of sexual desire when compared to popular films of the 1980s. I didn’t consciously pick this out as pre-Dune reading material, by the way; I catch myself returning to it periodically because it’s just that damn good. But Benedict shouts out 1986’s Blue Velvet and the character played by Kyle MacLachlan—who just so happens to have starred in David Lynch’s original Dune two years earlier. Funny how things like that work out, huh? So I went into this new Dune with perhaps a very unusual lens of analysis, one I’ve tried and largely failed to entirely parse out in my mind. With any luck, I’ll do a better job on my computer. I’m hesitant to say whether or not I liked Villenueve’s Dune, because I don’t entirely know the answer to that myself. I don’t intend for this to be yet another adaptation-rage article despite my continual defense of Lynch’s Dune; there were aspects of this new one I really liked, liked more, even. For starters, the rave reviews aren’t kidding when they say Villenueve’s Dune is stunningly beautiful. I also thought the score was a major highlight, which is always nice to see (or hear, I guess). The most honest review I can give is that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it, for better or for worse: it’s like my brain is a clam and this thing is a grain of sand that I’m trying to turn into a pearl of a blog post. And I like thinking about movies a lot, good or bad. But when I think about Dune in concurrence with Benedict’s article, there’s something undeniably off. For starters, nobody in Villenueve’s Dune really has a body. Between the fascist-lite military uniforms of House Atreides and the desert survival stillsuits of the Fremen, we’re treated to the film’s insanely attractive cast pretty much exclusively from the neck up. Even their faces are covered far more consistently than in Lynch’s Dune, perhaps in the name of rhetorical authenticity. Going further than that, so much of Villenueve’s Dune feels profoundly empty: sweeping shots of vast multi-planetary landscapes, self-sustaining sci-fi machinery or rooms too big and too beautiful to be lived in. People are frequently overshadowed by their surroundings, dots in the sand or appealingly shaped masses for a far-away camera. Rather than fetishizing the body, the way Benedict describes modern blockbusters do, Villenueve seems to fetishize the spaces and the spacecrafts that bodies occupy. It creates a world that is beautiful—I cannot stress this enough, beautiful—but undisturbed by human touch. When you look at popular reviews of this Dune, nearly all of them will mention the cinematography or the mise-en-scene or the worldbuilding, but far fewer will mention the actors who populate those elements. I think this contributes to my biggest disappointment in the new Dune: its depiction of the iconic Litany Against Fear, when Paul Atreides must prove himself to a Reverend Mother of the Bene Gesserit by sticking his hand into a box that causes him to experience excruciating pain. In Lynch’s treatment of the scene, Paul envisions his hand slowly burning up, the flesh charring and sloughing off as Kyle MacLachlan’s face contorts with agony. It’s simple, but effective—it makes me wince every time I see it. Villenueve’s take is far more abstract. When Timothee Chalamet’s Paul puts his hand in the box, he sees scenes of the Arrakis desert, his usual flash-forwards of what his life will be there, fire burning somewhere else, what might be an arm reduced to ashes but goes by so fast it could just as well be anybody’s arm, or a tree branch. These images are gorgeous, meticulously framed and shot, but they just don’t mesh with Chalamet’s exaggerated and at times comical facial expressions. He’s doing his best, I’m sure, but it’s much more difficult to turn this bodyless montage to a physical experience, especially when there’s no precedent that tells us Paul has a body he can feel pain with. And if we can’t even understand Paul’s pain, how are we ever going to possibly conceive of his pleasure? For all the cultural fascination he inspires, Timothee Chalamet is the weirdest part of the Dune equation to me. I worked really hard to come up with a way to say this without sounding too mean and none of them really landed, so you’ll have to cut me some slack: I find his screen presence across his entire filmography to be mostly sexless. Including films where he’s been in sex scenes! I don’t claim to be any expert at being attracted to men, but the Chalamet catnip eludes me. He’s a masculine ideal far from the sculpted Marvel hunks Benedict mentions, but his pretty-boy look is equally as micromanaged and crafted by innumerable hands. There is no possible way for an individual person with a regular amount of money to do the same thing. On the handful of occasions he’s shirtless in Dune, he evokes not a body but the image of a body, Benedict’s idea of a “collection of features”. When you see your boyfriend take his shirt off for the first time, he’s not going to look like Timothee Chalamet. He’s probably not going to look like Kyle MacLachlan, either, but Benedict’s point is that maybe he could. Timothee Chalamet and Zendaya are not going to fuck in Dune Part Two (if it ends up getting greenlit). If I’m wrong, I’ll print out this blog post and eat it. But I’m not going to be wrong, because nobody is going to fuck in Dune the same way nobody fucks in Star Wars and nobody fucks in the MCU, even when they have sex. It’s not about sex scenes; it’s about what Benedict calls “sex-haver energy” when she identifes it in 80s action heros like Kurt Russel’s Snake Plissken. Regardless of a film’s actual sexual content, it's about building the impression that this is an individual who experiences embodied desire for the world and for other people who experience the same desire. There’s a confidence inherent to it that goes well with the genre--the signal of a character that is firmly grounded within their world, within their own body and its interactions with the bodies of others. You know who’s a really good example of sex-haver energy? Feyd-Rautha, Sting’s character in the original Dune. Yes, that Sting. Feyd is the balls-to-the-wall insane nephew of Baron Harkonnen, effectively the ‘evil Paul’ in the similar way he was raised from birth to become a future political leader. He’s a major player in one of the first film’s most iconic scenes, an intense hand-to-hand Battle Of The Narrative Foils near the climax. I choose to remember him instead for the scene where he steps out of a steam chamber wearing nothing but a leather speedo for no discernible reason. I tried so, SO hard to remember why this happens plot-wise, and I came up with nothing. That’s why I’m obsessed with it. What the hell, right? It’s exactly the kind of 80s nonsense you would never see in a big end-of-the-year sci-fi movie today, and exactly what Benedict was going for in her description of how blockbusters used to be. What I would have given to be a cultural fly on the wall when millions of sexually repressed young Americans were first subjected to Sting’s oiled up, skinny-but-somehow-also-shockingly-muscular body on thousands of giant cinema screens nationwide. There’s no on-screen sex in Lynch’s Dune (that I remember), but as soon as you see this scene, you just KNOW that Feyd FUCKS. Big-time. As an interesting aside, Feyd is not in Villenueve’s Dune, despite being a major character in the novel and the original film. Some people are holding out hope that he’ll make an appearance in Part 2, as most of his big scenes are towards the end of the book, but I don’t have that same confidence; wouldn’t we have at least seen him bumming around with the other Harkonnens? I want to believe that his unexpected absence has everything to do with that absolutely fantastic scene. It’s completely antithetical to Villenueve’s aesthetic: over-the-top where he wants to be understated, nonsensical where he wants to be scientifically accurate, wasteful and awkward where he wants his film to run as smoothly as one of its many beautiful spaceships. Above all, weirdly horny where his Dune is, consciously or unconsciously, as barren as the desert planet it takes place on. I like the idea that this little thirty-second scene spooked Villenueve so much that he threw Feyd out entirely, not wanting to touch him with a ten-foot boom mic. Maybe he wakes up in a cold sweat haunted by the specter of that shit-eating, confirmed sex-haver grin Sting does when he puts his hands on his hips. So let’s talk about Villenueve’s Dune again. In comparison, Timothee Chalamet’s Paul Atreides has TERMINALLY low sex-haver energy. Some of it comes from his weirdly impressive boyishness; Chalamet is twenty-five, the same age MacLachlan was in the role, but his Paul could just as easily be fifteen. This isn’t helped by the extra dose of royal family space-angst that’s been applied to make him less of a Spiced-up Skywalker and more, well, a character re-written for Timothee Chalamet to play. More than this, it's because Paul is now situated in a film that draws Benedict’s take on the modern blockbuster’s relationship to the body out to an even more stark conclusion. Most films are still obsessed with the image of the body even as they strip it of its desires--Villenueve’s Dune is utterly indifferent to it. On Arrakis, a body is an afterthought, a prop that moves its person from one plot point, or one gorgeous CGI set piece, to another. It’s a struggle even to fully comprehend the embodied, physical feelings and experiences we see Paul have on-screen--forget the ones we imagine he could be having off screen. And it honestly makes sense, given the time period Villenueve is reconsidering Dune in. Has there ever been a period of human history where we were so woefully disconnected from our own bodies? Social media, pandemic, general slow-burn Apocalypse ennui… I’m sure I don’t need to go on. As Benedict mentions, people our age have never been having less sex. We’re certainly having less sex than our parents were when Lynch’s Dune dropped in ‘84. However you feel about his Dune, it was undeniably an expression of the time it was made in; Villennueve’s Dune is exactly the same. A disembodied empty film for a disembodied empty time that will be watched and discussed by disembodied empty twenty-somethings for however long it keeps a flame going in the ruthless Arrakis-windstorm of content. It’s just as that perennial film critic, The Joker, so insightfully observed; we do, in fact, live in a society. The universe of Frank Herbert’s Dune is a universe so far in the future that all technological achievement imaginable has already been tried and rejected; artificial intelligence led to a brutal A.I war, so there is not a single computer in sight. In Villenueve’s treatment, it’s easy to imagine that the exact same thing has happened to sex. PART 2: Lucas F on the Fun Spaceships I saw Dune recently and thoroughly enjoyed myself. I haven’t seen Lynch’s interpretation nor have I read the book. I do struggle somewhat with stories that concern a handful of very powerful individuals the lives and choices of whom dictate the lives and choices of countless unnamed and unseen individuals implied to be populating the story-world for a.) empathy is less readily fostered for very powerful people and b.) such stories – however inadvertently – frame the experiences of these powerful individuals as playing out in a vacuum incubated from the consequences wrought upon the unnamed and unseen masses, who are only ever implied to exist. Villeneuve’s Dune shirks this problem to the extent it can by using the Fremen as a stand-in for the laypeople, for those innumerable individuals in the galaxy who don’t belong to one of the select bloodlines. This is fine and cool and I’m pretty okay it. I was thoroughly compelled by the movie in the following ways:

Another thing that I find really interesting about science-fiction and fantasy stories is the limbo between our world and the story-world the dialogue exists in. It must be intelligible for us and yet sufficiently alien. Star Wars, for instance, doesn’t care too much about ensuring its dialogue its sufficiently alien: its characters are consistently sarcastic and reference ideas and objects and things specific to our world. Lord of the Rings exists on the other end of the spectrum: its characters are hyper-sincere and often their speech is barely intelligible, relying as it does on the countless specificities of that story-world/Middle Earth. I love that Dune goes down the hyper-sincere, barely intelligible route. I love it when I feel almost-but-not-quite able to keep up. I also find sincerity really refreshing in a world saturated by post-post-meta-ironic whatever yada-yada. I love when movies trust the viewer to be able to roughly track the general contours of the narrative and themes and leave some stuff as subtext, freeing them up to do more interesting things narratively and thematically. That said, choosing to explicitly communicate everything to the audience is not a bad thing as such. Anyways, fear is the mindkiller and Denis Villeneuve is probably the most consistently impressive director working today. 4/5 grains of psychedelic spice. PART 3: Lucas W - The One Who Actually Read the Book Having read the book, my main worry going into this film was just how the hell it was going to get out the immense amount of information you need to know about Dune (even just the first half) in a decipherable way. However that was obviously Denis Villeneuve’s main concern as well and I couldn’t be more grateful for the care with which he approached it. I’ve heard other people express frustration at its slow start, a totally fair reaction for someone going in blind, but I was personally so happy watching all of that slow intricate worldbuilding play out. One subversive technique I noticed was that right after some big complicated sci-fi word was spoken (Bene Gesserit, for one) the dialogue would often switch to a different language or the Atreides hand signals, so that the audience could just read the word off the subtitles. Turns out that (at least part of) the answer to how you make a film out of an “unfilmable” book is to make your audience read. Villeneuve’s talent for grandeur is also on full display here, and I really liked the realism with which he approached many of the designs. I won’t deny that most of the enjoyment I got out of my viewing experience was from the incredible world and story of Frank Herbert’s Dune, but Villeneuve’s entire job here was to make room for that story to shine, and to him I say: Mission Accomplished. PART 4: Phil on Having Not Really Seen The Movie I haven’t been greatly anticipating Dune. My older brother read at least the first few books in the series in high school, but unlike Tolkein, Herbert wasn’t one of the writers I picked up from him. Most of what I picked up about the book made it sound more like a reference work than a novel and sci-fi/fantasy worldbuilding is often where I tune out. I enjoyed both of the Denis Villeneuve films I’ve seen, Enemy and Blade Runner 2049, but neither made Villeneuve feel like a director I needed to seek out; they were good films, but they didn’t connect with me on any deeper level than that. Still, I regretted missing a chance to see Dune in theaters with other BAMPFA blog writers in order to get work done even if getting work done was the right thing to do. I had mentioned Dune to one of my roommates when I was initially planning on going to that theatrical screening. It turned out he’d never heard of the movie or the book. Completely unaware that a movie or book called Dune existed or who any of the actors are, although he recognized Dave Bautista from wrestling when I showed him a picture (after trying to describe him, saying, “No, you’ve definitely seen him, he’s got this face… you’ll recognize the face if you see it.”) So I was surprised when, on this Tuesday evening, he said he was thinking of checking out Dune. I mentioned that it was on HBO Max, although everyone’s been saying not to watch it that way (when he asked me why people are saying not to watch it that way, my explanation came out, “Well, I think it’s big. You know, there’s like a lot of large… stuff in it.”). That didn’t deter him, although I let him know I would have to duck out for a bit to conduct an interview for this blog. Before we started the film, he wanted to know what Dune was. Being the one with slightly more knowledge, although I did make it clear I hadn’t read the book, I gave him a rundown based on half-remembered posts I’d read: “It’s the future, but there’s no computers, because they got rid of the computers and instead space travel has something to do with psychics and psychedelics. There’s Spice, which is important, because it gives you visions and lets you travel through space, and there’s a Spice planet called ‘Dune,’ and the leader guy puts people in charge of it to take the Spice from the native Free-men. So the planet ‘Dune’ is in the control of bad guys, the Hart-Conans, and that’s a good thing to have control of because it’s got the space hallucinogens, and then the Atreides are put in charge by the leader guy. Paul Atreides is a chosen one, and then Lawrence of Arabia happens.” Having half-paid attention to the movie, I still believe this to be largely true. We put Dune on, but almost immediately my roommate asked more questions over the opening narration when they were presumably explaining a lot of what was going on, and I tried to answer based on what I had gleaned, so I didn’t really get that exposition, although I think I got the gist: the Harkonnens are bad and the Fremen are against them, Spice is cool, and a new group of people is taking over from the Harkonnens. Now I started losing track at this point because I was antsy about conducting the interview so I started checking the time on my phone and going over in my mind whether there was any more prep I could do, and once the phone was out I had to start fiddling with it and looking at apps, but there was something about Paul doing a voice and a lot of images of big ships. I think I got through some training sequences, the sparring match with Josh Brolin and the weird hand box thing, before having to leave to conduct the interview. I came back and there was some battling, the Atreides had been kidnapped, more magic voice stuff. I don’t know, look, at this point I was revising an assignment and going through emails, occasionally glancing up at Dune. My roommate who had wanted to put it on decided to go get boba with somebody and left. Most of what I took in was the score, which I did not care for (those vocalizations bring back memories of the worst of 90s new age). The things I did see looked silly and unconvincing, but I imagine if I had been invested I would have bought into them, and also it was being streamed on a TV with a less-than-stellar internet connection, so it was not exactly being presented in optimal quality. It would have made sense to turn the movie off, since the roommate who had originally decided to put it on wasn’t there any longer, but for whatever reason I let it play out. I guess once the movie is like two hours of the way through, you might as well finish it. I can’t draw any conclusion on the movie because I might as well have not seen it. The best I have is, “Dune: It’s a movie that was on in a room I was in for most but definitely not all of the time it was on.” by Beck Trebesch This fall has been a distinctly democratic one for the ski movie industry, with a seemingly unprecedented number of flicks dropping for free on Newschoolers, skiing’s famed internet forum, or YouTube. I, the diligent skier I am, have been doing my best to keep up as the mid-sixties palm tree balm of Northern California intensifies my lust for waist deep snow, kinked handrails, and cork 3 safeties. With there being so many exciting, independently created films available, I felt it was only right to compile a compendium of the best the sport has had to offer ahead of the new season.

Entourage - YAKTV. (Bozeman, MT, USA) What the fuck is a YAKTV, you might ask? Is that some strange, out of pocket Barstool Sports reference that I’m just not getting? Thankfully, it’s not but unfortunately, it does stand for “You Already Know the Vibes.” And I did already know the vibes going into this one, following my scathing review of Entourage’s last film Collage. To my surprise and enjoyment, YAKTV. was a seriously notable improvement on the hodge podge, gimmick fest that was the last installment. The editing was more to the point, the filming made more sense, the skiing went harder; I couldn’t help but enjoy this 24 min helping from the crew. I would also like to commend Entourage’s successful pursuit of debuting the film at the Rialto Theater in Bozeman (theater debuts are a theme for this year). With our internet feeds being so saturated with content day in and day out, attaching a film to a public, tangible, lived experience, especially one where a large portion of the Bozeman community is participating, is seriously valuable in making this art meaningful, inclusive, and sustainable. Carnage - Wasted Potential (Bozeman, MT, USA) In my piece about Collage, last year I was going to cite Carnage’s last film, Subject to Change, as the beautiful, well-formed antithesis but time prevented me. A year on and the Carnage crew are still delivering gritty, unfiltered yet truly heartfelt productions to the absolute diehards of Bozeman’s freeride skiing population. Spitting with personality like Swift after a healthy hog of Copenhagen, this is the filmic equivalent to going to a Montana rodeo and successfully hijacking a bucking bronco or, more appropriately, Fritz’ snowmobile (sled in the local vernacular) erupting in flame at the start of the movie. Music is as important as ever in the extreme sport edit landscape and Wasted Potential exceeds with its eclectic employment of punk, metal, nu metal (let’s go), 2000’s hip hop, and alternative dance, pairing carnage to cacophony, smooth snowriding to silky synths, and Rage Against the Machine with the gnarliest sled segment in recent memory. There is such a consistent energy throughout this movie that materialized by the rough showmanship by the guys at the premier which I was lucky enough to go to in Bozeman the day before my 21st birthday. The after party was pretty fun, too… SNP MT - So Not Pro (Missoula, Montana, USA) To round out our Montana entries for this year is Missoula/Bozeman based crew SNP MT and their film, So Not Pro. With the other two Montana offerings fitting into a more classic ski film standard in regards to camera work and song choice, So Not Pro felt like it was more heavily informed by elements of skateboard/street culture. This was evidenced in stand alone shots, grungy but varied soundtrack, and the emphasis on urban skiing. For those who know William Strobeck’s style, characterized by slow frame rates, intense zooms, and straight forward angles, then Grant Larson’s undertaking becomes all the more recognizable as a tribute, worship even to that culture of videography. This was a super fun watch, with all the boys chipping in with big drops, precise rail sliding, big grins, and bone crushing slams across the 37 minute run time. They premiered this not once, not twice, but three times in Bozeman, Missoula, and Boulder, CO and for good reason. The public needs to see this. Deviate - Good Luck (filmed in Wyoming and Idaho) Here we shift gears from the up and coming amateur to the established pro. X Games medalists and famed stylers Jossi Wells and Torin Yater-Wallace teamed up with fellow pros Chris Logan, Birk Irving, and Cody LaPlante to put together an effortless package of backcountry booters, supple pillows, and jagged spines. It’s just a good, honest flick in ski movie terms. Nothing groundbreaking shot-wise, music-wise, vibe-wise. I can commend it for prompting me to say “wow, that’s big” on multiple occasions but in it being so clean (it is a Redbull sponsored project), so non-confrontational, so conventional, it didn’t quite stick with me like the other ones on this list did. There’s no doubt Chris Logan has the craziest cork 7 japan axis on the market right now but bottom line, I wish this one had a little more bite. Child Labor - Take 3 (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) Do you like watching grown men wearing beanies and smoking proper slam into asphalt streets and concrete walls covered with a vague amount of ice and snow? Do you need an education in style? Do you like Death Grips? Child Labor’s Take 3 has you covered in all departments in their new full length. The Utah crew are back with some of the best ACL-crunching, mind bending urban skiing in the amateur field. Cal Carson continues to be an absolute magician, Brolf got the Yung Lean makeover cut, Dakota is seen wearing a helmet, and Bennie is hippity hopping his way through Mormon country with ease; there’s a serious mystique about this crew embodied by Bennie emerging from a manhole cover to then hit a rail. The fisheye camera and nimble follow cams are serving these boys well too. My only gripe with this one is that while they took some really admirable risks with the soundtrack (Death Grips among multiple mashups and genre fusions), it did kinda kill the momentum of the film compared to their last one, Don’t Fret. But… Do I want them to change? Fuck no. Keep these children toiling away. Forre - Forrmula (Ruka, Finland) We round out with one of two international films I wanted to include in this year’s roundup and this one cannot, CANNOT be slept on. Probably the most strikingly beautiful film on the list, the Forre boys take to the grand streets of Finland and inject their own unique brand of technicality, style, and all out disregard for safety into the urban landscape. The amount of one of a kind features and spots they found in this movie might be a record breaking first for any ski movie I’ve ever seen. It’s not everyday you see someone grind a public sculpture made of abstract shapes or jump out of a 3 story graffiti-soaked, abandoned warehouse to near dead flat. Watching public urban form take center stage in this masterpiece was really refreshing. Also, the variety in everyone’s individual style which manifests in some seriously diverse trick selection leads to a dynamic yet compact experience. This really is the skier’s ski movie and there’s no doubt Forrmula was well worth the 10 dollars I paid for it. Suede - Rip in Pieces (Stockholm, Sweden) Rip in Pieces is not a mournful affair. Far from it. It’s celebratory. It’s innovative. It’s artful. Filmer/editor Emil Larssen combines one part patience, one part nimbleness to create a really, really fluid set of stunning skiing vignettes, spearheaded by our main cast of characters for the first 20 minutes. The introduction is truly something to behold. The Aegan blue ice graphic melts seamlessly into a slowly zooming shot of the Swedish backcountry, a temporal tribute to the environment, the molecules that make the sport possible. Filmic properties aside, the skiing in this movie is so fun to watch. These guys know their way around a ski. Nose, tail, edge, base; all parts got adequate attention on a series of urban features where just when you think the line or the trick is over, something else pops out. The Suede boys might not be going as big as some of their counterparts on this list but they make up for it with ingenuity and commitment to doing the right trick at the right time. I mean I don’t know I’ve ever seen a cork 7 lead safety look so goddamn good. Can’t wait for the next one. Entourage - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F25VakhuTgQ Carnage - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTG_j33QSow&t=1314s SNP - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ot0of6nuaTA&t=1303s Deviate - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPU1a9y1nNg&t=1152s Child Labor - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2mOtYThSAE Forre (not free) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VtLEczD4ZA&t=657s Suede - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4bUkTTr1iE&t=3s by Natalia Macias weave stories

into my hair dark brown rebozo glitters red silk in the sun my protector carry the young to their destiny weave stories into their hair about their blood, their skin about the things they will never get to see cover their heads with the rebozo of your mother the one she claimed as her second skin help it find its way back to the soil where she knelt tending to the earth so weave weave stories into my hair my blood, my skin etch it into the backs of my eyelids let it warm me as the cloth of a thousand colors, a thousand lives silence envelops me i don’t hear so much as feel the smooth beating of your heart the sun peeks through the space in between the weave and i tug at a loose thread connecting you and me cover my head eyes closed my veil as the stories of those that have kept me company in solitude preserved by the stillness falls to pieces at my feet in lifeless puddles of night within the folds of the cloth smuggle pain across borders wrap this second skin tight tighter don’t let your blood find it’s way back into the soil my eyes, my skin, my blood you are not who i thought you were from hand woven stories to synthetic lies let it be my protector let it be my veil let it be mine porque el olvido is a dangerous thing so sit down beside me and weave your stories into my hair n.m. by Phil Segal The Mill Valley Film Festival recently wrapped. I was lucky enough to catch five screenings, four at BAMPFA, one (Ninjababy) online.

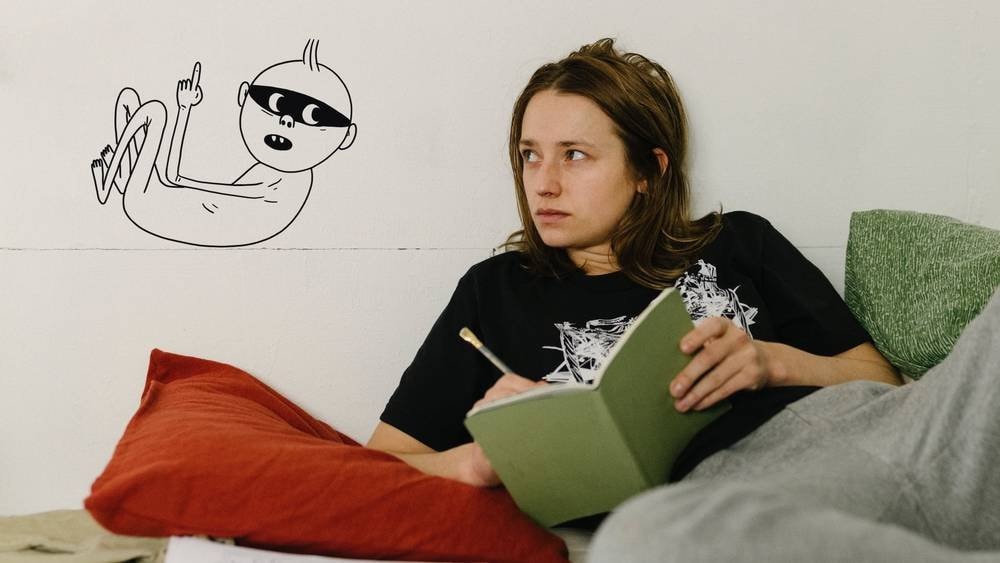

Memoria Apichatpong Weerasethakul has always been happy to let audiences’ eyes and ears wander around the frame at their leisure rather than controlling their attention (he likes minds wandering, too). Despite some worries I had about an “English language debut” featuring, at least compared to his previous work, a superstar, putting Tilda in the movie hasn’t changed anything: she’s just occasionally one of the things in the frame that you can choose to focus on, a useful tool compositionally because her body is a powerful set of lines. In the earliest days of film, shots would be composed to utilize lots of diagonals to create something visually dynamic in spite of a frequently stationary camera; frequently here Weerasethakul does the same, holding stationary shots that nevertheless keep your eyes in motion, and he has painter’s eye for arrangements of color and light as well. Even the shots that went on for minutes I felt like I hadn’t finished looking at and hearing. The purpose of shots is not to advance what little plot there is but to create visual and aural arrangements to be appreciated in the moment; if you can approach it in that way, it’s a generous, welcoming experience. Lingui, The Sacred Bonds Two sisters, long estranged, have a tense meeting in which one is unwilling to budge. Until, that is, the other sister mentions trouble with her husband, providing a catalyst for the two women to unite. This Chadian drama celebrates women watching out for each other in a world where men can’t be relied on or trusted and makes the case for the necessity of safe access to abortion. It’s well-performed, incredibly timely, and uplifting. What it isn’t is very cinematic, with veteran director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun sticking to the standard realist style of modern message pictures, but the lack of distinctive film style is ultimately inconsequential compared to what he does right with his screenplay and his handling of tone. The film doesn’t downplay the struggle its characters face or how serious the risks they take are, but focuses on resilience and resistance, resulting in an ultimately energizing film rather than the noble downer you’re likely expecting from a film about abortion rights. Ninjababy Rakel, the heroine of Ninjababy, also wants an abortion but finds out she’s much farther along in her pregnancy than she realized despite showing no signs. She frustratedly declares that it must have been some kind of “ninjababy” in order to sneak up on her like that. An aspiring graphic novelist who’s constantly scribbling on the scenes around her in her mind (one of the inventive blendings of animation and live action throughout the film), it’s not long before she’s drawn the “ninjababy,” which immediately takes on a life of its own, popping up on papers and walls to argue and make demands, much to her chagrin. Yngvild Sve Flikke’s film is an unusually raunchy, strange, and frequently hilarious look at an unwanted pregnancy, a film with characters called things like “Dick Jesus,” a sequence featuring stop-motion sperm, and one of the more charmingly irresponsible mothers-to-be in film history. In the end things get more heartwarming and sincere, and that’s all handled well, but it’s the crude and comical (in multiple senses) journey to get there that’s the original and exciting part Bergman Island Mia Hansen-Løve’s latest is another confirmation of her impeccable skill as a filmmaker. Her films are some of the most fluid being made right now; every scene ends a little before you expect it to, hard cutting the moment someone finishes talking or comes to rest, so that there’s a ceaseless momentum to her films, and the frames always include exactly what is necessary to convey information about her characters and no more for only as long as it takes to absorb that information, so that your attention is continuously stimulated and carefully controlled. It’s truly auteurism in that it creates the same effect as literary narration, the world described with a distinct voice and point of view, through visuals and cutting. An identifiable “prose” style runs through her work, the filmic equivalent of the brisk, well-constructed sentences of a Hemingway or Didion. I was slightly disappointed by what she wrote this time out, with the qualification that I’ve never had any attachment to Bergman, although as the film goes on and adds new layers it becomes more interesting. If her previous films like Things to Come hadn’t set the bar so high I would probably be more impressed by this one, which is quite good but no Things to Come. Graded against anyone other than herself, though, it’s an unqualified recommendation. Drive My Car Drive My Car is three hours long, with a narrative that unfolds in a relaxed, winding manner, and yet I never felt my attention flag or that anything Ryusuke Hamaguchi opted to show wasn’t adding to the film. A lot happens in the lives of the characters we meet over the course of the film without it ever quite feeling like a plot. The interest is not so much in seeing how one thing will lead to another; instead, it’s just what these characters will do in each situation they encounter, where their conversations will take them, because they come across as rounded people full of contradictory impulses and motives that aren’t always clear, even to themselves. Adapted (apparently loosely) from a Haruki Murakami story, the film deals with the world of theatre, large parts revolving around rehearsals for a multilingual staging of Uncle Vanya. It’s in part a film about the power of art to bring people together, to help people process things that happen to them, and to reach across time and space to speak to us. Mainly, though, it’s a film about people, the steady accumulation of detail over the three hour runtime reminding us that there are few things richer and more mysterious than what goes on within and between human beings. by Phil Segal Ahead of the CineSpin event on November 12th when they’ll providing an original live score to Kote Mikaberidze’s Russian silent film My Grandmother, I had the chance to talk with musicians and composers Gabriel Sarnoff and Miles Tuncel. You can check out music by Gabe and Miles here (Miles appears on track 2, “Satisfaction”). Our talk covered improvised music in the Zoom era, what makes accompanying a film particularly exciting, and what they hope people will get from the CineSpin experience.

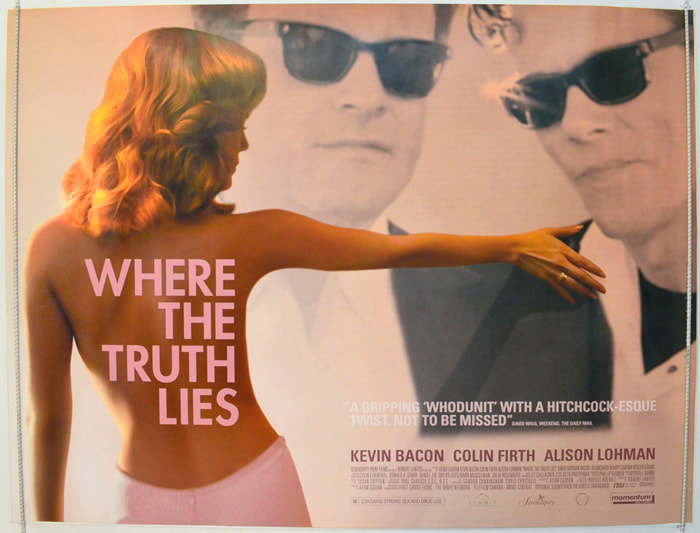

BAMPFA SC: Why don’t we start with an introduction and go over what led you here? Miles Tuncel: Hi, I’m Miles, I play primarily saxophones. I’ve been playing saxophones for ten plus years now, since I was in middle school, and I met Gabe in an ensemble at Berkeley-- Ben Goldberg’s class, who’s a big hero and teacher of ours. We sort of took off from that, improvising and composing together, playing a lot of different genres of music, a lot of different settings. We also played in Myra Melford’s group on campus, which is an improvisational based music class. I’d say those two classes and those two people have been huge inspirations for us in terms of how we approach composing and improvisation and playing with each other. Gabriel Sarnoff: To go off that, I came at music starting in ninth grade. I started playing guitar, played in a pretty “hard rock” band throughout high school with some buddies, and then towards the end of high school got into playing upright bass. I was the electric bassist of this band, and then wanted to play upright base, joined the school’s small orchestra (I went to a tiny school), and that’s what got me into reading music and classical music. Then I came to Cal, studied music as one of my double majors, and met Miles in that class in our junior year, and from there kinda found myself in this corner of the music department at Berkeley, and just generally music in the Bay Area, of improvised music primarily. Ben Goldberg and Myra Melford are pretty well known in that area of music, very respected, and they’ve become mentors for us. We’re following in their footsteps but doing our own thing. We approach music I think a bit more from— at least I do, and I think Miles as well— Miles has more of a jazz background whereas I have more of a rock/folk background, but we both appreciate that other style of music, and so we come together and create a synthesis of the two and pair it with improvised music to get something really special that we think will go well with the silent film. We’re excited for this opportunity because it’s super-unique, to say the least. BSC: How did you end up getting this opportunity to do CineSpin? GS: I think I got an email. I’ve known about this event, I went to it two or three years ago, and I was like, “Wow, I really wanna do this! This is so cool.” So I saw the email and we sent in a song that we had made for a new jazz ensemble. We actually sent in a song that we made over Zoom, because we were doing everything over Zoom during COVID. BSC: Were you improving over Zoom? MT: Yeah, it was a big part of our lives for a year or so. It was a really different experience trying to play music over Zoom. It’s a difficult prospect but it led to some interesting results. We would never really have thought about playing music or composing in the ways we did before everything happened. GS: For example, the song we sent in, we were playing along with a friend of ours, Evan, who was in this ensemble with us. He was playing bass clarinet I believe, [Miles] was playing saxophone, I was playing guitar, all over Zoom. I think it was completely free improvisation, there might have been some melodic structure that we were basing it on, but Evan was using a pedal that pitch shifted what he was playing, and that wasn’t coming across to us. He was hearing himself play completely different than we were hearing him play, and it led to a crazy sound that wouldn’t have been possible had we been playing together live without that filter between us of Zoom. So the Zoom/COVID era opened up a lot of doors for musicians doing free improv music. I think for musicians working in more rigid forms where everything has to stay in time, they were probably kind of screwed, but since we’re not based in a time signature or tempo, things are looser in free improv, it led to interesting results. We realized that you don’t have to hear everything that everyone’s playing at once to create something beautiful. You only hearing what one person in the ensemble is playing, and that person only hearing what a different person is playing, it creates really interesting results. BSC: I’m interested in your approach to working with film because Gabe, I actually had the chance to view a talk you gave (viewable here) on representational aspects of music and how that affects composition. Could you explain a bit about that, and maybe that can lead us into how you worked with this film? GS: Yeah, so my theories on composing and music are pretty abstract and mainly exist in my head, so they’re probably not too logical, but I guess the basic idea of how I see music, how I hear music, is as a narrative form. A good example is when you’re listening to classical music, like an orchestra playing, there’s usually a lot of people playing but only a few melodic lines going on at a time, because if you do more than four or five at a time no one’s gonna know what’s going on. I hear each of those voices as kind of characters in a story. If I’m listening to a piece of music and it’s guitar for a while, and then the bass comes in, it’s analogous to when you’re watching a movie and following a one person for a while, and then a new character walks in and joins the storyline. I think it’s a very valuable perspective, because when you’re working with music it’s very abstract. People can get caught up with doing too much and adding too many elements just because you can, especially in our digital age when you’re working on computers and have the option to add hundreds of tracks on top of each other. Some people do that, a good example being Jacob Collier, who’s a composer and musician that’s pretty well known. He’s big on that, putting three hundred vocals on one song, all on top of each other. That’s its own thing. That’s not my approach. My approach is that if you’re writing a story, you’re not going to have three hundred characters, or no one will know what’s going on. I prefer music with fewer elements, with each element more developed. That being said, the movie My Grandmother, we just watched it for the first time, and it’s a very hectic movie [laughs]. There’s a lot of… It’s more of that Jacob Collier side of things with a million different things happening. In this project, for us, one thing I was thinking about when we were watching the movie, is that we can’t match that with two people playing live. We’ll have to create something that can have a contrast to the movie. If we were doing a film score where we recorded everything and were able to compose meticulously, that would be one thing, but live we won’t be able to match the superfast cutting and rapid changes of events. For example, there’s a scene of a guy sliding down a railing on a staircase, it’s a recurring thing, and I’d love to go [imitating slide whistle] to mirror him, but I think we’re going to try and exist in a separate dimension, where we’re not necessarily mirroring everything that’s going on but the instead aiming for the contrast of the music to give meaning to the movie and the movie to give meaning to the music. That was a lot [laughing]. BSC: Miles, do you share Gabe’s theories of music or do you take a different approach to thinking about it? MT: I’d say that reflected my sort of way of approaching music pretty well in terms of storytelling and character. I think the music to me that is the most interesting, and I guess this expands to all art, is where it’s not something perfect, where you can hear the artist struggling to achieve something. It’s not perfect, but it’s what they have, and they’re putting all they have into it. I think in terms of scoring things, that’s where our experience in improvised music pairs well with scoring a movie, because in improvised music you can have so many kinds of interactions between people: between the performers, a conductor, the audience, so there’s a great fit between interacting with a movie and improvised music performers. BSC: How does that play out for you? The film is something rigid, locked in, it’ll be the same every time. Is it freeing for you to improvise against because you always have that baseline, locked in thing to return to no matter how far out you go, or do you find that restrictive, that you can’t go out as far? MT: I think that can be freeing, and that’s something important in music, to have some kind of structure that the listener can lock onto and say, “Oh, I know what’s going on here.” So I think it’s a good baseline to build off. And there’s all kinds of baselines in music that you can build off and take form from, so I think this is just another one of those structures to add music to. GS: If I can add, I’m taking one on one lessons with the clarinetist Ben Goldberg we mentioned earlier, who teaches improvised music at Cal, and in these one on one lessons we’re basically working on melodic improvisation over chord changes. So the music we’ve done with Ben and Myra in the past, and what we’re going to do for this movie, for the most part, is the opposite of what traditional jazz is. There, you have a sheet of chords, and for four bars it’s a C Major, and then it’s a G, and then yadda yadda yadda. In our kind of free jazz improvised music, we’re only following our ear with no predetermined chord structures, which leads to a huge realm of possibilities. But, in these lessons I’m doing the opposite, I’m working on going through these chord changes and creating a mental map that you can use to anchor what you’re playing. What I think is cool about this movie project is that the movie takes on the same role as the chord sheet in a jazz standard, and we can use that to anchor our playing. In the course of the next few weeks we’re really just going to learn this movie as if it were chord changes. It’s going to be impossible to memorize every single action in the movie, but generally we’ll know, “Oh, this is going to happen next.” If we have that really under our fingertips so we don’t have to think about it, that’s when it frees you up while you’re playing. The biggest thing is that we’re improvising and we won’t be talking, so we have to have something— usually it’s our ear— keeping us together. If we both know what’s coming next in the movie, though, that’s going to create wild possibilities. We’ll both know a crazy scene is coming up, and that will influence our playing, and so we’ll… I don’t know! I don’t know what’s gonna happen, but I think it’s so unique. So my answer is that I don’t think it’s limiting. Quite the contrary. BSC: If I could bring us back a bit to your talk, you mention there that normally the audience doesn’t have direct access to the images or feelings the composer means the music to represent. Here, we in the audience are going to be looking at the image you’re trying to represent at the same time you’re looking at it and trying to represent it. What effects do you think this will have, will it be more challenging for you, does it take away something by limiting possible interpretations? GS: I was thinking about this. We watched it last night, actually, and we were just brainstorming. I was thinking about what I mentioned earlier, that we can’t match everything in the movie as two people playing live, it has to be a freer connection between the two, but since the audience will be seeing the movie and us simultaneously they’ll create connections we weren’t even imagining. That’s my plan. MT: Yeah. GS: I think the audience’s brains will play a big role in creating the meaning behind the music, in an abstract sense. BSC: So everyone will get their own experience of it. It’ll be totally open in that way. GS: Yeah. BSC: So to prepare for this, is there any music or anything else you’ve been drawing on? Have you been listening to film scores, or jazz/improv, or looking for inspiration anywhere in particular? MT: Yeah, I think we’re always playing what we’re listening to. I’ve been listening to a lot of Wayne Shorter recently, he’s one of my favorite saxophone players. There’s this record that’s fairly recent, in the last ten years, called Without a Net, that I think is very good at representing a story. I think that record is some of the saxophone playing that I’m always striving to match in terms of storytelling and being a character and having your own voice. GS: Definitely we should be listening to more film scores. To speak for you [points at Miles], he’s been listening to a lot of… I’m not sure where it’s from, but this flute music. MT: Oh yeah, it’ s a Turkish ney, it’s a kind of flute. GS: Miles influences me a lot because he shows me a lot of world music with instruments I’ve never heard of. A lot of times in the US, and Western popular music, songs are pretty rigid and three to four minutes, so it’s nice to hear something a bit more fluid. Film scores are like that as well. A film score is probably where people living here, like students at Berkeley for example, get most of their long fluid music. It reaches them through movies. I definitely think I’m inspired by the music Miles has shown me, as well as finding a way to merge some of the other work I’m doing right now. I’m creating folk songs, or like Bob Dylan-y singer-songwriter-y songs, wondering if there’s a way to bring stuff like that, maybe some singing, to the film score table, but we’re still parsing together everything. BSC: Do you think film scoring is something you’ll want to explore more after this? GS: Definitely. As a musician— I just graduated Cal and now I’m trying to pursue music full time— a career in film scoring is one of the more stable careers for a musician to have, if you can make it in that area, so that’s really appealing to me. I think as an artform, I still haven’t explored it enough. That’s why I’m really excited for this project. I see this as an artform that no one’s really doing, pairing this kind of improvised music with silent films. If it goes well— I think it’ll go well— I’d like to do more of that specifically moreso than just film scoring in the traditional sense. MT: Agreed. by Truly Edison There is probably no movie that I defend more frequently or with more intense passion than Atom Egoyan’s dead-in-the-water 2005 murder mystery, Where The Truth Lies. If you’ve never heard of it before, you are DEFINITELY not in the minority; the only other people I know who’ve seen it are people I’ve literally watched it with. I’m the proud owner of its only English-language five star Letterboxd reviews. I’ve written poems about it, used images from it in visual art, and all around been a complete lunatic about it since high school. I rewatched it last night with a close friend of mine who had never seen it, and the time has come to finally admit something I never wanted to say: Where The Truth Lies is not very good.