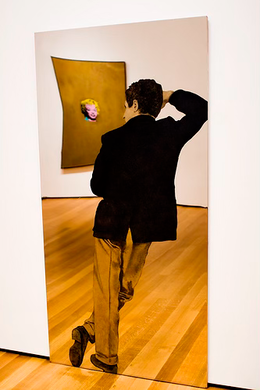

by Sophia Limoncelli-HerwickIn Artifact and Art, Arthur Danto writes that “What makes … artwork is the fact that, just as a human action gives embodiment to a thought, the artwork embodies something we could not conceptualize without the material object which conveys its soul” (Danto 31). I agree that artistic intention and conscious symbolism play an integral role in the creation of “artwork,” but I take issue with the implied notion that artifact, and therefore craftwork, is not artistic. Why should we strip handiwork of its cultural and historical significance because it doesn’t possess deliberate spiritual meaning? Symbolic import may be what makes something a work of art, but symbolism is so intrinsically open to interpretation that anything handmade with the purpose of being at least somewhat aesthetically pleasing can be art. What’s more, as a unique, handmade product of a specific period, every individual piece of craftwork inherently possesses Walter Benjamin’s concept of the “aura” (Benjamin 23). Tenderly brought into existence under particular cultural and historical circumstances, craftwork denies the mechanical reproduction of objects that kills traditional and ritualistic value. Mexican weaving, for instance, produces elaborate textiles that can be worn and used, but the designs of the items also exemplify the specific cultural heritage of each community that the works were made in. Danto’s philosophical experiment in which baskets and pots from different cultures can look precisely the same yet retain different values as art versus artifact further fortifies my point that craftwork can be art. Though distinguished as art objects versus artisanal objects contingent upon their spiritual significance in each respective culture, the fact that they have the same visual, aesthetic properties means that utilitarian objects can be called art. John Dewey and Albert C. Barnes assert that the distinction between craft and art is sufficiently weak and elastic (Danto 27). If we treat art as formal design, as an appreciation of not just intention but simultaneously physical appearance, there is absolutely no reason to exclude craftwork from the realm of art. Denis Dutton asks, “If we treat utilitarian objects as works of art, is it not a mistake because they are mere tools” (Dutton 2)? Though practical use is their primary value, I question the need to make such a harsh division between craftsmanship and art. Does Chinese pottery not serve a similar visual purpose as a Piet Mondrian painting in terms of geometry? Simply because something has a functional purpose does not mean that it cannot be art; many modern art pieces incorporate items that have practical purposes into their work. Consider Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Man with Yellow Pants; he uses a mirror, a utilitarian object, as the canvas for his piece. The practical use is an element of the work, but not the defining aspect. The painting of the man is. This same argument can be used for studio crafts; yes, they have practical use, but they also possess an element of beauty and handiwork that can classify them under the term “art.” Art and craftwork are not mutually exclusive. Why must we perpetuate such a strong boundary between a Pablo Picasso and an intricately woven Yup’ik basket? As Michel Foucault writes in Death of an Author, an artist’s name often applies significance to a piece, but if we forgo the fame of the creator and compare a post-it note sketch to a knit scarf, why is the drawing “art” yet the scarf is a simple utilitarian object? A sketch that took perhaps thirty minutes to complete may be stuck above a friend’s bed, proudly displayed, but the scarf is neatly folded in a wardrobe, hidden away from view until it’s necessary to be worn and used. We fail to consider that baskets, glassware, ceramics, clothing, and countless other studio crafts all incorporate similar amounts of time, dedication, effort, and even aesthetic consideration to construct as any given painting, drawing or sculpture. Let’s say that the scarf took longer to produce than the sketch; just because it’s not a figural or symbolic image, it’s not art even though far more physical effort went into creating something beautiful? Hands created the scarf just as they created the sketch, and to distinguish the scarf as less valuable is to disregard the human nature inherent within anything handmade. Employing the most fundamental level of formal analysis, it’s indisputable that the design and physical production of craftwork makes it art. Sources: Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, 1935.

Dutton, Denis. “Tribal Art and Artifact.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 51, no. 1 (December 1, 1993): 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540_6245.jaac51.1.0013. Stevens, Phillips, Arthur Danto, R. Michael Gramly, Jeanne Zeidler, Mary Lou Hultgren, and Enid Schildkrout. “Art/Artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections.” African Arts 22, no. 1 (November 1988): 18–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3336683.

1 Comment

by Ashley Margolis “Anne Carson is a Gemini. Because, of f****** course she’s a Gemini.”

The above text is one of many I sent to my Gemini coworker over the course of the summer of 2022; it also encapsulates the two major occurrences of that summer, which were that:

Example 1: The book title. What do glass, irony, and God have in common? Why has Anne strung them together with flimsy commas and a brazen “and,” and slapped them on the front cover as if those subjects relate to each other at all? It’s not entirely about the contents of the book, either. It’s true that there’s a section called “The Glass Essay” and another called “The Truth About God,” but none of the section titles breathe a word about irony. And, to that end, there are a bunch of sections that are not referenced in the title. Why isn’t the book called “Glass, TV Men, and God” or “Isiah, Glass, and Sound?” Not that those titles make any more sense to the blind viewer who is too afraid to crack the book open in the middle of the store to skim the section titles than Glass, Irony, and God does, but you get my point. Why does it feel like Anne is teasing us before we’ve even committed to buying the damn book. What do glass, irony, and God have to do with each other? Why has Anne forced them into close proximity, and why is she daring us to join them? What the fuck has Anne’s confusing title got to do with me? Why am I handing the cashier $17 and walking out of the bookstore with a lightness behind my eyes? Here’s a fun fact for you: Anne Carson is a classicist. She studies ancient Greek and Latin, and it is damn near impossible to forget that when you’re reading her books. Alternative fact: I was deeply and stupidly in love with a 20 year old philosopher who taught me how to play clawhammer banjo when I was 18. She would not let me forget she was a philosopher when we were together. Mostly it was in her eyes. That and she was always talking about Descartes’ epistemology. It probably would have been more productive to hang a “do not disturb” sign up in those eyes than to even attempt to decipher what she was thinking about at any given moment. She also absolutely detested poetry. She said that she hated things that she didn’t understand. I found that especially rich coming from someone who studied philosophy and played clawhammer banjo, but, you know. We kissed once and then never again. I didn't quite understand that. She told me I kissed very fast. Frantically, like I was waiting for someone to pull the rug out from under me. Obviously she didn’t actually say that last part, she hated similes. I stopped writing poems for a while after we stopped being in each other’s lives; I didn’t have anyone to try and prove wrong anymore. Example 2: Anne is talking to you and you should probably listen. Reading an Anne Carson book is like holding something up to the light and trying to figure out what’s shining through the other side. She as the author makes you as the reader do half of the work at any given moment, she’s clever like that. Anne writes in an inherently confusing manner. It is easy enough to follow when the poem’s subject is alone, but the whole thing gets tangled up when other characters are introduced. Her dialogue generally abandons quotation marks or any other reliable notation of separation between subjects. The proximity goes all out of whack. It seems a little itchy and unpleasant at first; we don’t like the things we don’t understand. Personally, though, I adore it. I feel that reading Anne isn’t about comprehension, the work she asks of you is almost entirely emotional. She throws you directly into the weeds in her depiction of relationships, forcing you to start untangling fast or admit you don’t like poetry and put the book down. She’s teasing you again. You really thought you could make it through the book passively? Not a chance, Anne won’t stop talking to you in the second person. Right when you start to feel like you’ve got her, right when you’ve become the bouncer outside the club who just held up your friend’s very fake Connecticut driver’s license to reveal that it has no microperforation on the back, you realize that Anne got your ass. She was the one holding you up to the light the entire time and you didn’t even notice. Anne Carson writes narratively, not autobiographical. It was around the third readthrough of Glass, Irony, and God that I realized I was just as much a narrative device as the TV men were. When I annotate her books, I write to her in the second person. She’s talking to me, it only seems fair that I talk back. I told the Gemini coworker about Glass, Irony, and God sometime before we kissed for the first time on a night before I was scheduled for a 5am shift at the coffee place we both worked at. I made sure I kissed slowly this time. I don’t think I ever saw her show up to another shift on time after that night. I don’t quite get that part, either. I helped her move into a room of an ancient house near a loud intersection and a bar that definitely wouldn’t clock a fake Connecticut driver’s license if it slapped them in the face, microperforation be damned. She gave me a bookshelf that she didn’t have the space for anymore. I keep my Anne Carson books in there now when I’m not loaning them out to my friends. I never knew who to be when the two of us hung out. I felt like the wrong answer, not that she ever gave any indication that she comprehended either one of us as conscious and tangible human beings, but I thought maybe that’s just what it was like to be 24 so I tried to be 24. She bought me vegan thai food the day she gave me the bookshelf, I would say that was the most romantic thing that ever went down between us. I presume that was probably by design. I spent a few months in the summer listening to obscure indie music she sent me and reading Anne Carson’s poems and trying not to look at my phone and then it just stopped one day and we never spoke about it again. I was better at making coffee when I wasn’t trying to be 24, I think. Example 3: Why do you keep putting yourself in the path of things you know are going to absolutely body you? This is the thought that runs through my head every time I’m buying a new Anne Carson book. I want to say that I own seven of them these days, although two are currently lost to the ether of friends’ apartments. The biggest danger of Anne’s books is that you will probably finish them in one sitting when you really shouldn’t. You also probably shouldn’t go over to a philosopher’s house for a clawhammer banjo lesson two days after she said you kiss too fast and one day after she said she would really rather not kiss you ever again, actually. You also shouldn’t go to a brewery in Alameda when you’re underage without a fake Connecticut driver’s license that says otherwise just to try and impress your Gemini coworker who kisses you when she’s bored, mostly. I like to think that I don’t jump the gun quite as severely as I used to. Getting older is such a funny thing, I fear. I don’t get paid to make coffee anymore, I play Scruggs style banjo instead of clawhammer now, and I tattooed a star on my ankle like I said I would forever ago. There’s a beautiful satisfaction that comes with keeping a promise to yourself. You have to go slow with Anne, but I swear that it’s worth it. She's taking a lot of time out of her busy schedule of being my favorite contemporary poet to sit and talk with you between the pages of “The Glass Essay,” after all. We owe her the respect of a few pencil annotations in the margins to let her know that we hear her and we can feel her holding us up to the light. by Colbie Mahaffey She woke up, and groggily walked to the bathroom, splashing water on her face before looking up in the mirror. She drew back, then leaned in closer, squinting slightly at the sight of the dark circles under her eyes. They looked unnaturally dark, like she had a bruise, or dirt under her eyes. She rubbed them, and it didn’t hurt like a bruise, or rub away like dirt. Confused, she decided she must just be really tired- after all, she had been working late recently. She would go to bed early tonight and look better in the morning. When her husband woke up, she mentioned the dark circles to him, but he stared through her eyes and shook his head, “You look the same to me!”

The next morning, she was horrified to see her eyes looked even worse. The bags under her eyes were so dark that her once bright green eyes now looked sunken and her skin seemed droopy. But still, no one else seemed to notice. Over the next few weeks, she began buying eye creams and following home remedies, but no matter what she did, the circles under her eyes only got longer and darker. Until one morning, she was pulling at the circles in the mirror, and her fingers sunk straight through her skin, as if ripping through wet paper. And she kept pulling down, until her entire face was falling off, and under it, her skin hung raw and bloody. Moaning through her lack of a mouth, she walked to her husband, who glanced up without batting an eye, and said “Morning sweetie”. She looked the same to him. by Bibi Koenig I'm talking about that one building on campus that constantly spews out opaque white gas. Old, dilapidated, missing windows, strangely art deco-y with pilasters at the corners. Looks like a child or two may have died in it when labor regulations weren't as strict. You know the one.

Due to a lack of a better term, my friend Elisa calls this structure the "Toxicology Building." I too will refer to it as such. I cannot remember my first encounter with the Toxicology Building. But, I can say that every time I see it, I have the same distant yet completely apparent thought that something seems very off and potentially dangerous. There was once an entire week in which I passed by the Toxicology Building and smelled the stench of gas, persistently. And while this did concern me, I didn't do anything about it. I'm not a chemtrail conspiracist, but I feel like I should care more about mysterious gasses. Maybe I, like many other college students, secretly hope for a disaster so I can sue the school and get free tuition. But I already get free tuition because my dad busted his knee while playing soccer for the U.S. Navy. So I really don't know why I think this. Maybe it would be kind of cool to be part of a generation of slightly genetically-damaged UCB students. Like an X-Men situation, but instead of doing cool things I just hope that somebody gives me a job for my art history degree. Anyways, it actually wasn't very hard to discover the true purpose of the Toxicology Building at all. While there was a part of me that expected a long, sordid past of dark deals and chemical warfare stuff, maybe some MK-Ultra shadiness, it turned out all I needed to do to find out more was go on Google Maps, identify the name of the building, and then look it up. So, the Toxicology Building isn't the Toxicology Building it all. It's known as both the "Central Heating Plant" and the "Cogeneration Plant." Right beside it is the "Hazardous Materials Facility," but ironically I have no interest in investigating this adjacent building further, so I simply will not. The Central Heating Plant/Cogeneration Plant, or "Toxentral CoHeauilding Blant" as I would now like to christen it (there's no official pronunciation; choose one) has been spoken of a few times by various sources. Berkeley Facilities Services claims that the Toxentral CoHeauilding Blant provides 100% of UC Berkeley's steam needs and 90% of the campus's electricity needs. Where it loses me is that it doesn't state where the other 10% is from. Very suspicious. I assume there are goblins in a basement somewhere on stationary bikes coughing up the rest of the energy. Also, a website straight from the institution would never tell us if a child died in the building, so I don't really trust it as a source. BFS also claims the Blant operates 24/7/365, which makes me curious as to what would happen if it stopped. The obvious answer is Lucas would die, but what one may not realize is the campus very well might lose power! Tobin Fricke provides the earliest account of the Toxentral CoHeauilding Blant that I could find. Published in 2001, his blog post offers detailed insight into the workings of the Blant, including several images of '90s computers. While Tobin claims "any of the information here could very well be wrong" because he had "written it all from my memory," I'd like to counter this by saying a man so honest could never be incorrect. Tobin says the interior of the building is hard to take pictures of because it is tightly packed with ducts, pipes, and equipment. He also did not have access to an overall plan of the Blant. So it seems like you could maybe hide a small body in there somewhere. Jeana Lee of the Daily Californian immediately loses me because she claims the building goes unnoticed and unquestioned by most students. However, I begrudgingly reference her because she does seem to know what she's talking about. She says the Toxentral CoHeauilding Blant was built in the '30s (child labor?), but did not become a cogeneration plant until 1987. The Blant burns 150 pounds of coal a minute and is responsible for 71% of Cal's CO2 emissions, so it will have to be replaced or shut down in order to reach UC Berkeley's carbon neutral goal by 2025. Despite all the information I uncovered about the Blant, I am more concerned with what I could not find: an explicit statement that no child has died in the building. Anybody else with the misfortune of being from San Diego is likely familiar with the Nuclear Boobs, (officially the San Onofre Nuclear Power Plant) a power plant between San Diego and L.A. that looks like, you guessed it, some boobs. And I still remember the deep, shared sorrow I and my brave contemporaries (the other people at my high school) felt when we found out that the Nuclear Boobs were being shut down permanently. This sorrow is similar to what I feel for the Toxentral CoHeauilding Blant–uncertainty, nostalgia, and the sentiment that I am face-to-face with a relic of the past that can no longer do what needs to be done for the people. Fly high, Toxentral CoHeauilding Blant. Although I'm not really sure if it's actually going to stop spitting out gas all the time, or if they’re ever going to admit that a child died in the building, this surely is the end of an era. Just remember, if that beloved dame of a building decides to go Chernobyl on us, you know where to find me: at Strawberry Creek. Drinking the water. a piece of narration from the upcoming film noir by famed filmmaker and professional alcoholic Hugh Wonderbang a spoof by Magellan Reyes “I slammed my fist on the table, mad that she wouldn’t share with me all her dirty little secrets. I knew she was there when Bobby met his untimely demise, but the dame just wouldn’t crack. The putrid musk generated by all these dirty little lies gets caught in your nostrils and layered on your skin like grease, and no amount of baths’ll clean ‘em out. I was sick of what she had to say, sick of dames giving me the run around, sick of the whole damn thing. I grabbed her by the shoulders and shook her good, tell me what you know I said. I didn’t mean to be so rough, but it didn’t seem to work anyhow. The dame just sat there, laughing like a wicked witch damning me to hell. Well she can damn me to hell as much as she wants, I thought, what do I care—I’m already there. She cursed at me as I made my way over to the bar. She told me I was just a lousy drunk, that I didn’t know nothing and never would. But I didn’t care. I was tired. This life has a way of wearing a man down, of turning all he loves against him. She cursed at me again as I downed my glass of whiskey. But I ignored her, and just poured another drink…” by Natalia Macias shades of melancholia

i let my clock fall three minutes behind then four and with the changing of the season it becomes 56 minutes ahead i let it because it doesn’t mean much to me my body never really observed it’s rigid lines likes more of the mental gymnastics it takes for me to calculate the difference between the bedside clock and the number on my phone, the one in my mom’s car and the one above the stove, … i calculate my age for the day even by the hour it changes traveling from 17 to 21 to 54 my body would expand to create years in the span of a couple of hours when i close my eyes time looks like my stretch marks expands, retracts breathes in and out since the last time i’ve seen it my body says see how i’ve grown look at the new space i’ve created our connection to time isn’t new love but ancient recognition it isn’t shivers and goosebumps, it’s reverence and sustained power just below the surface of your skin sometimes i feel like a stone in a zen garden the sand moves like water around me making serene landscapes … i calculate the amount of grief i’ll carry with me today i often underestimate, but it’s okay the weight of the many versions of myself that i’ve lost tug at the hem of my jeans who i could’ve been, the lives i promised myself forced to slow down i realize i live in shades of melancholia and not wanting it any other way i do wish i could separate the two realities jump from one to the next all at my convenience but for now i live in them both simultaneously mourning quietly and with any empathy i can spare feeding a new found fascination with dichotomies and the painfully bright way they merge … my body often forgets it’s own language the different regions have new slang and their accents make it hard to understand and when my body forgets it’s own language it only knows how to scream my body has made the space in between my home standing on the cusp of overwhelming sound and complete silence familiarizing myself with uncertainty and many people only pass through but i’ve been trying to make it my home building upon shifting land i wonder what my body would say if you asked it what it feels like to live in the space in between n.m. ~ a reflection on crip time by ellen samuels by Lucas Fink What is it to be gentle? What makes someone, something, or some act gentle? I think gentleness could be said to entail an exploratory hesitance, a tentative curiosity, a desire to know the object tempered by a hyperawareness of the object’s rich affective life-world. A desire to approach and wrap around and feel without disturbing. I might have been wrong to say “know the object”, at least insofar as knowing/looking are extractive operations and are therefore operations that always disturb, that always condemn the object to legibility. Moten and Harney on hapticality might be helpful here. For them, hapticality is not merely a more capacious account of common feeling, and is therefore not a brutal liberal appeal to the universality of human affects and experiences. Hapticality does not designate any one emotion or collective emotional circumstance; rather, hapticality is the act of feeling someone else feel you (Moten & Harney 98), a feeling through the other. Hapticality is love, then. Gentleness is a mechanism of love, for the hyperawareness of the object’s rich affective life-world prompted in and by the caring apprehension of gentleness is the condition of possibility for hapticality/love in the first place. The awareness that the object has/is a life-world, that I also have/am a life-world, that I am also an object (for you), and that finally the boundary between our two life-worlds is porous at best and phantasmatic more likely. Gentleness, finally, is this slow, sensitive movement through the world of things, a movement motivated by the desire to caress and to be-with always already contextualized by an awareness of the multiplicity of desires out there in the world of things blossoming beyond you. A sub-genre of empathy, a desire to experience alterity without rocking the boat, without violently imposing the Self over and above it.

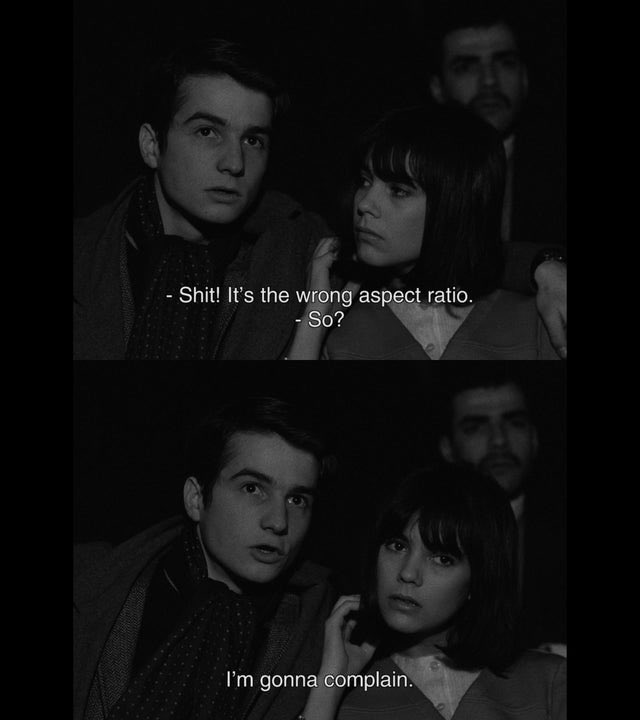

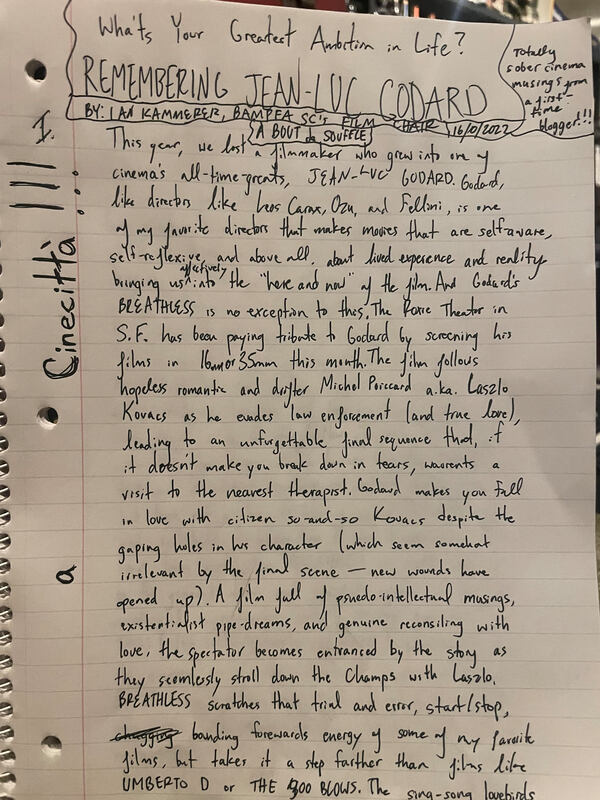

The vine next to my bed has been growing steadily for the past 3-ish years. At some point in those last three years, I tucked the vine under a wooden plank in my bed frame and let it continue growing over and on top of the frame. It has now arrived at the other end. The plant’s other vine drapes lazily down over my reading light and tissue box. What interests me most about the modality of movement these vines instantiate is the interplay (I’m sorry but I like that buzzword better than dichotomy) between their exploratory eagerness and receptivity to my guiding their exploration. Wherever I let them hang, whatever I wrap them around, the vines will – with a Mediterranean lethargy – happily come to know the room’s spatial specificities (as long as they get light). Am I circumscribing their exploration more than merely guiding it? Maybe. Am I harvesting from this plant the earthen eco vitalist aesthetic its appearance lends? Or is it enlivening my apartment bedroom pro bono, imposing on me a debt I can never hope to repay? Anyway, unanswerable questions. What is in fact certain at this point is that the vines are gentle. Does a thing have to be alive to be gentle? Does it have to move (so it can move slowly)? More unanswerables. Obviously this picture fails to capture the vines’ gentleness because pictures cannot capture movement (absenting maybe time-lapse photography and such). You can see the history of its movement, though, the trail it took to get where it is now, the little gap between boards where I notched it, the suggestion of an infinite vine produced by the visual omission of the vine’s terminus at the other edge of my bed. I guess its movement is there, then, as a trace. Again, though, does gentleness necessarily imply (slow) movement? If a thing moves, does it need to move slowly for it to be called gentle? Life-saving CPR isn't very slow, nor would most of us call it gentle. It's life-saving, though. Odd. Lots of things move, though. Architecture moves: a pillar moves into a cornice moves into a cupola moves into a weather vein. Movement need not bear any easily legible, linear temporal orientation. This is why I love this plant: it goes, just not forward. It goes around and loops and dives and extends, but never goes forward, nor backwards. A movement without a telos. It just wants to feel. I love the way the sunlight plays with the leaves and their shadows. Were the shadows already there, hiding under the leaves, waiting for the sunlight to arrive? by Henry Donald It's fine. If you came to House of the Dragon hoping to be delivered to the heights of Game of Thrones season 4, you will be sorely disappointed. Or for that matter seasons 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. There are plenty of visually stunning battles, Lannisters, Targaryans, and Dragons, but the show lacks what made its predecessor and sequel so enthralling, the dialogue and structure that endeared (or detested) us from its characters and their fates. Hampered by an extravagant budget, House of the Dragon is too quick to depict incredible battles and majestic dragons, missing what made them so enjoyable. Additionally, a focus on female empowerment and its ostensibly more progressive outlook than Game of Thrones is undercut by the obviously self-aggrandizing tone and propensity to depict violence for shock value.

One of the most striking differences between the opening episodes of Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon is the dialogue. Characters in Game of Thrones speak cleverly and often with distinction, but their lexicon is not unfamiliar to the viewer. Undoubtedly aided by the superior acting of Game of Thrones, communication has subtext upon subtext: Tyrion and Cersei and even Ned weaving witty remarks, parental advice and threats together seamlessly, often in the same words. Monologues, when they do occur, feel truly menacing or inspiring: Tyrion’s pleas at his trial and Baelish’s pronouncement that chaos is a ladder still ring in my ears. Conversations feel natural and dramatic, each line further characterizing the characters as containing complex and contradictory motives to country or house or family. In House of the Dragon, conversation feels coerced in search of drama, concocted by writers who preferred consulting a thesaurus of old English to literature. Written in a terrible replication of Shakespearian language with none of the complexity or heart that made Shakespeare Shakespeare, you can practically hear the writers’ room when any character speaks, awkwardly mixing antiquated sentence structure with more modern speak. Aesthetically this pulls the viewer from their engagement, but hurts the characterization of the show on a deeper level. When writers resort to platitudes rather than wits, preferring to proffer contrived dramatization to genuine moments of connection found all throughout Game of Thrones, they deprived the viewer of an opportunity to learn more about the characters, what motivates them, who they love, why they are fighting. Relationships aren’t given a chance to evolve, and viewers aren’t enabled to connect with the characters but instead marvel at them. The structure of the beginning of Game of Thrones is brilliantly paced. Battles come rarely, and when they do are epic and memorable, dragons take seasons between their introduction and destruction. Blackwater and The Battle of the Bastards remain as memorable as the day I viewed them. The time skipping of house of the Dragon absolutely demolishes its own structure. To engage with a climax, there must be a rising action. When you jump right into fire and pageantry you offer nowhere for the viewers’ expectations to go but down. Without a proper build up, the writers of the House of the Dragon have cornered themselves into delivering on impossible promises, to one up themselves eternally when their budget will only stretch so far. Additionally, the time jumps break the continuity of the show. We don’t care about the triarchy or the Crabfeeder, as he is only a villain for three episodes. Even if he is not a main antagonist, the failure to even attempt to portray him and his motivations fails the wider purposes of the characterization of Daemon and Rhaenyra. We are told the war has lasted three years and caused great harm to the seven kingdoms, but how are we supposed to emotionally connect with exposition? House of the Dragon attempts to claim the exalted status of prestige drama entirely offscreen, fast forwarding through the character growth, and aftermath of conflict, and catastrophe that would make the audience care about the show. The pacing of Game of Thrones built up to the epic heights of Hardhome and the Red Wedding like a methodical chess game, each player playing the long game, trying to outsmart their opponent, moves taking seasons to pay off, building suspension for that eventuality. House of the Dragon simply has Paddty Considine exclaim it’s been however many years at the beginning of each episode. You can’t have the payoff of epic battles without the care put into constructing the participants so that you care about the outcome. Finally, and potentially most egregiously, House of the Dragon attempts to claim its spot amongst the best of HBO by blatantly appealing to the current political climate rather than the more essential and timeless humanistic themes of literature. While certainly not perfect, mainly in terms of later character arcs and depictions of sexual violence, Game of Thrones portrayed powerful female characters. Dany, Arya, Cersei, and Sansa amongst others had competing loyalties to friends, lovers, children, power, bannermen, common people, religions, and trades. They had rich histories and growth marked by self-empowerment. By appealing to the classical themes of literature, love, obligation, duty, honor, greed, but recontextualizing them in the hands of women protagonists, too often ignored in high fantasy, Game of Thrones successfully incorporated feminist ideals. By granting female characters autonomy and depth because they were characters equally as worthy of attention as male characters, they were able to help bridge the gender gap in prestige television and media as a whole. House of the Dragon is proud of its female protagonists. It puts them front and center in the marketing, producers talk openly about how childbirth is the real battlefield and every other character in the show reminds the audience that a woman should never ascend to the Iron Throne. While women in Game of Thrones were constrained by the patriarchy, their struggle was encapsulated in implicit systems of control, dehumanizing acts of obedience, and derogatory dialogue. While Game of Thrones could have reined in the obscenity, this more subtle approach to depicting the patriarchy proved to be more effective at demonstrating its ubiquity and strength. When characters in the House of the Dragon make reference to it, there is not nearly as widespread a depiction of the struggles women in Westeros face, the show preferring to skip over the more mundane but potentially overbearing and brutal methods of control to the girlboss moment of defiance. Sansa’s ascent to power was impactful because the viewer understood the forces she was up against, personally and politically. When House of the Dragon shows the victory without the struggle, it cheapens the fight, breaks the immersion of the show, and undermines its messaging. The showrunners also show their priorities clearly even in the first episode with over the top violence not even seen in Game of Thrones, most noticeably in an excruciatingly prolonged childbirth scene. Watching the scene felt like gore, festishing the struggle for the sake of purely shocking the viewer. Instead of spending her short lived screen time fleshing out her character, we watch her suffer and bleed out on her childbearing bed. The showrunners preference for shock over nuance is just as apparent in their continual use of child marriages. Suggesting marriages between adults and infants, a king decades older than a prepubescent child is a pastime of the small council. They are introduced with such fervor you are made to consider not the destructive nature of child marriage but rather question how far the writers will go. This scenes are handled without delicacy, and while central characters act disgusted at the prospect, there is no wider examination of the culture that encourages it. Showrunners can’t claim to aspire to feminist messaging when they would so easily undercut those messages to shock the viewer in a misguided belief that simply showing the brutal effects of oppression is acceptable instead of depicting how those oppressive systems function and can be demolished. House of the Dragon’s main draw is the emotional attachment viewers have to the original show. I watch it because even if it isn’t as good as its predecessor, I get lost in intricately crafted fantasies, and House of the Dragon provides more depth to the works of George RR Martin. I admit I am entranced by dragons, battles, and admittedly simplistic and obviously set up drama. Even every once in a while I’ll appreciate a snappy back and forth. I worry that by continuing to engage with House of the Dragon, I am supporting a model increasingly dependent on intellectual property and drawing in viewers by spinning off ridiculous numbers of projects from an initially enjoyable franchise. I critique it because I want it to be better, to not only exist in the same world as Game of Thrones but to live up to it. 2.5/5 ~What is your greatest ambition in life? To become immortal then die~ REMEMBERING JEAN-LUC GODARD10/19/2022 totally sober musings from a first time blogger by Ian Kammerer This year, we lost a filmmaker who grew into one of cinema’s all-time greats, Jean-Luc Godard. Godard, like directors like Leos Carax, Ozu, and Fellini, is one of my favorite directors that makes movies that are self-aware, self-reflexive, and above all, about lived experience and reality, bringing us affectively into the “here and now” of the film. And Godard’s Breathless is no exception to this. The Roxie Theater in SF has been paying tribute to Godard by screening his films in 16mm or 35mm this month. Breathless follows hopeless romantic and drifter Michel Poiccard a.k.a. Laszlo Kovacs as he evades law enforcement (and true love), leading to an unforgettable final sequence that, if it doesn’t make you break down in tears, warrants a visit to the nearest therapist. Godard makes you fall in love with citizen so-and-so Kovacs despite the gaping holes in his character (which seem somewhat irrelevant by the final scene — new wounds have opened up). A film full of pseudo-intellectual musings, existentialist pipe-dreams, and genuine reconciling with love, the spectator becomes entranced by the story as they seamlessly stroll down the Champs with Laszlo. Breathless scratches that trial and error, start / stop, always bounding forwards itch of some of my favorite films, but takes it a step farther than films like Umberto D or The 400 Blows. The sing-song dialogue of Laszlo and Patricia, which like the actual sing-song lovebirds Genevieve and Guy from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, end this fateful tale in heartstring-plucking resolutions. What stuck out to me was the underlying theme of the dangers of the ego in the modern era. Laszlo is constantly interacting with performance, from speaking to a headshot of “Bogey” and proclaiming the famous “a Cinecittà!” to making faces in the mirror to Patricia and himself. The stress of the dangers one encounters when overly-indulging in themselves and their ego, paired with technology comes through in the film strongly. Now, even more than in 1960 when the film came out, do humans have the technology that can do almost everything we used to do for ourselves but have not a clue or hair of moral forthrightness and fortitude to know how to use it responsibility. This fear looms over us in Breathless, adding to the general doom and agony of the film’s emotional superstructure Similar to my favorite film of 2021, The Worst Person in the World, Breathless uses the cinema as a quasi-theatrical, quasi-personal monologue yet liminal space where once self-indulgent diaries seemed pretentious and egotistical, now seem interested, genuine, and necessary. Breathless does something that precious-few films of late do, which is to tell the truth. Godard tells it to us straight. Shit happens. Love fails. Truth evades honesty. “Informers inform. Burglars burgle. Murderers murder. Lovers love.” And above all else, “There’s no need to lie. Truth is best.” Thank you Godard, for having the power to tell the truth. You have become immortal to us through your films, which will live on in our minds like the last touch of a lover lingers on our lips. Until next time.

FIN via dailybeast by Phil Segal 1. Crime in General